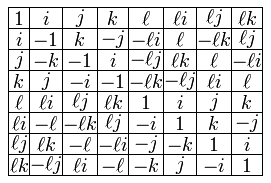

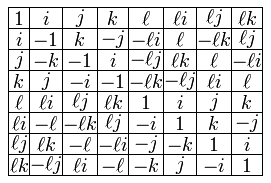

My student John Huerta is visiting me in Singapore and we're writing a paper about a ball rolling on another ball without slipping or twisting. If the rolling ball is actually a spin-1/2 particle and the fixed one is actually a projective plane, the space of their possible positions is the same as the space of light rays seen by someone living in a 7-dimensional universe with 3 time dimensions and 4 space dimensions. And when one ball is exactly 3 times as big as the other, something even better happens! Then the whole problem has the same symmetries as the split octonions: an 8-dimensional number system whose multiplication table is shown above. Then the 7-dimensional universe consists of the 'imaginary' split octonions, those at right angles to the number 1.

The fun thing about math is that I'm not joking: this is actually all true. Honest.

When drum 'n' bass exploded onto the scene in the 90's, stripping dance music down to its minimal elements, one of the most intelligent practitioners was Rupert Parkes, aka Photek. His music is atmospheric, jazzy, but a bit cold and often intensely rhythmic.

This, the title tune from his 1997 album Modus Operandi, is at the mellow end of his spectrum. It's 'music for staying up too late': the sort of thing you want in the airport cafe at 3 am when your connection is delayed.

At first it sounds like nothing is happening, but gradually you realize that about nine different nothings are happening: a simple jazzy drumbeat, an electronic piano lick, a deep bass line, a jazz guitar lick, various whooshing sounds to serve as transitions, a quiet steel drum pattern, a piano melody, a synth playing a string-like tone as a kind of drone — and way behind them, at the very brink of audibility, the sound of children playing in a schoolyard. Each is carefully chosen to be so cool in emotional tone that the music sounds like it's just waiting for its flight to show up. It's somewhere between soothing and unsettling.

April 6, 2012

The title track of Photek's Modus Operandi is chilly late-night mood

music, but the first few tracks form a chain of linked pieces that

become increasingly energetic.

Track 1, "The Hidden Camera", starts with a deliberately cold and unpromising electronic piano riff: a ploy. Then comes a whoosh and the main characters appear: a double bass and a twitchy, jagged drum pattern poised between the catchy and the chaotic. To really enjoy Photek to the fullest, you have to listen to that pattern, get to know it, and try to mentally 'sing along with it'. Then you'll notice, for example, that around 2:25 he cleverly pulls the rug out from under you.

But more easy to appreciate are the elongated, dreamy synth lines that sweep like clouds over the rhythmic bed, making us attend to two very different time scales: the near-millisecond scale of the percussion, and the 10-second scale of these long notes. It's when our attention is saturated that music gets really pleasurable! Our brains like being used.

Track 3: "Minotaur". This is what I've been leading up to all along. True to its title, this piece sounds like a giant beast chasing you through an underground labyrinth!

It starts (and ends) with an off-putting raspy sound — you'll love it after the tenth listen. At 0:45 the first main character enters: a repetitive melody on very deep tuned drums. Though simple, it's unresolved enough, with enough empty space, to sustain the whole piece. But only at 1:51 does the tune reveal its full intentions: extra rhythmic elements, including distant blasts that remind me of titanic footsteps, fill in the missing spaces and give the piece a truly earth-shaking character.

The piece here ends abruptly, so if you like it, buy the whole album — Modus Operandi by Photek — and hear how it segues into the next one. The whole album is perfect for its kind.

Since drum-n-bass music is often called "dnb", it made sense for Photek to title a piece "dna". It has a curious use of jazz guitar... and can you figure out what time signature this piece is in, or what's the underlying principle behind the strange, lumbering beat? I like fancy rhythms best when they swing and I can follow them in some rough intuitive way even though I can't rationally figure out what the pattern is. That makes me keep coming back for more.

This is off his 2000 LP Terminus.

A lot of Photek's old fans are disappointed with his new music, and it's easy to see why: while albums like Modus Operandi bristled with tense intelligence, some of his new stuff seems to fall back on dance music clichés. Take this piece, "Cecconi", from his 2011 Aviator EP. The chord sequence of the melody, and the way its timbre gradually shifts, is something we've all heard before. And the breaks at 1:09, where 5-note bits of that melody alternate with silence — that kind of stuff really tires me.

But wait... what rhythm is he using for the melody? I believe it's 11/4! At least, that's what I count during the parts where he's not shifting it around. Count yourself and see.

So I think he's decided to see what he can get away without us noticing. In a 2008 interview he said:

I'm going to some amazing lengths and I've got an amazing guy who I am working with who is a visionary, Dr Henry Nicholas — an amazing scientist basically. I've been talking to him a lot about pioneering new ground. I've been reading a lot more than I've ever done; strategy, philosophy, neuroscience."

This 1997 piece is a classic of Photek's early, twitchy, aggressive style. It's also one of the few music videos on YouTube where the video actually helps. This piece is an intricate composition of drum, bass, and snippets of sound from Japanese martial arts movies - most notably, the clash of sword on sword. It's a truly athletic piece. In his 2008 interview, Photek said:

... the track "Ni-Ten-Ichi-Ryu" (Two Swords Technique) is literally a musical representation of the technique of fighting with a long sword and a short sword. This is a technique created by Miyamoto Musashi . a Japanese historical samurai figure. I grew up doing martial arts before I got into music. Basically, my martial arts suffered from that (laughs), because I was just in the studio sitting in a chair clicking a mouse rather than out there training.I completely disagree with the callous brutality embedded in the samurai philosophy, but single-mindedness, fearlessness and the ability to rally immense energy to the task at hand are qualities I'm always trying to cultivate. You can see the whole mixed package in Musashi's The Book of Five Rings:

When we are fighting with the enemy, even when it can be seen that we can win on the surface with the benefit of the Way, if his spirit is not extinguished, he may be beaten superficially yet undefeated in spirit deep inside. With this principle of "penetrating the depths" we can destroy the enemy's spirit in its depths, demoralising him by quickly changing our spirit. This often occurs.Penetrating the depths means penetrating with the long sword, penetrating with the body, and penetrating with the spirit. This cannot be understood in a generalisation.

Once we have crushed the enemy in the depths, there is no need to remain spirited. But otherwise we must remain spirited. If the enemy remains spirited it is difficult to crush him. You must train in penetrating the depths for large-scale strategy and also single combat.

IceCube is a neutrino detector built in the beautifully clear 18,000-year old ice deep beneath the Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. When a high-energy neutrino hits a water molecule, sometimes the collision produces a muon zipping faster than the speed of light in ice. This in turn produces something like a sonic boom, but with light instead of sound. It's called Cerenkov radiation, and it's the blue light in the picture. This is detected by an array of 5000 photomultiplier tubes — those gadgets hanging on electrical cables.

One thing this artist's impression doesn't show is that IceCube is amazingly large. It's a cubic kilometer in size!

If you were a physicist you could work here! The South Pole Station has 200 people in the summer... but fewer than 50 in the winter. The station is completely self-sufficient then, powered by generators running on jet fuel. After the last flight leaves and the long dark begins, they show a double feature of The Thing (a horror film set in Antarctica) and The Shining (about an isolated hotel caretaker). They also have their own newspaper, The Antarctic Sun.

Right now the big news is the discovery made by the IceCube neutrino detector. This lies deep beneath the snow: even its very top is 1.4 kilometers down, to minimize the effects of stray cosmic rays.

This Christmas saw a heat wave that set a record high temperature: -12.3 degees Celsius! But by April 7 the temperature dropped below -100°F (-73 °C), less than three weeks after the one sunset of the year.

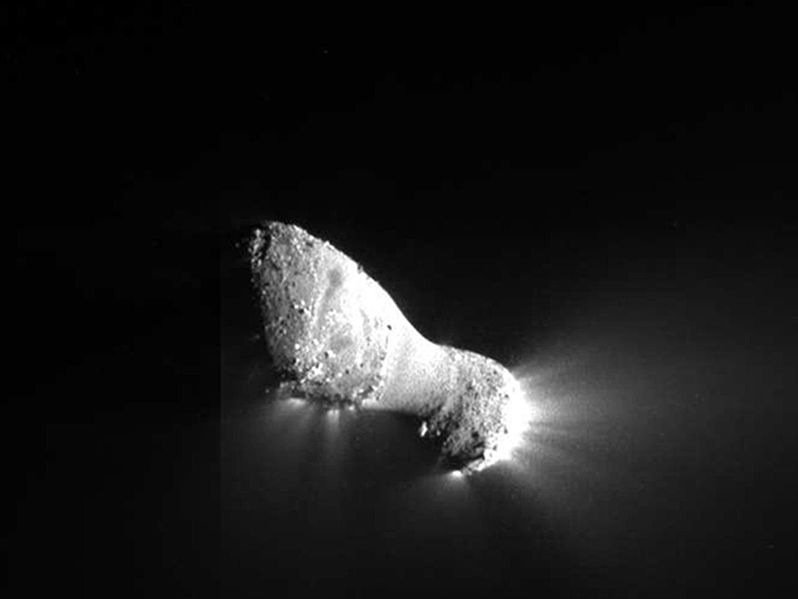

Here's the nucleus of Comet Hartley 2, blasting carbon dioxide into space. This photo was taken by NASA's EPOXI mission in 2010. They were originally going to fly past a different comet, but amusingly when the time came, they couldn't find that comet! Luckily they could change plans in midflight.

This flight was also a test of the Interplanetary Internet. According to Vince Cerf, celestial motion, planetary rotation, and delays from the speed of light all impair communication over distances on the scale of our solar system. Delay and Disruption Tolerant Networking solves these problems and seems to work better than TCP down here on Earth, too!

April 26, 2012

National Geographic has a blog written

by people who are now climbing Mount Everest. Here's Sam Elias

training in the Khumbu Icefall

near the Everest Base Camp:

As usual, it's the Sherpas who impress me most:

Years of experience, or maybe the mountain itself, had told the Sherpas that passing through the Ballroom on this day was not a good idea, something would happen. "Big ice will fall." Panuru's words echoed in my head. "How do they know?" I wondered.I was sitting in my tent fitting my crampons onto my boots when I heard it. I know the sound now. Before, when the loud rumbling began I instinctively thought of a giant semi barreling down a highway. But there are no vehicles here.

Also:

Every year, the route through the Khumbu is set by the "ice doctors," a small team of Sherpas who take mortal risks to navigate the safest passage through the Icefall, putting up ropes in the steep sections and stretching ladders across the abyss-like crevasses.

Crossing the ladders is an adventure for some. For the Sherpas, setting them up is a job.

Suppose you take the southeast route to Mount Everest, on the Nepal side. When you climb up from Base Camp, the first thing you'll hit is the Khumbu Icefall, a crazy and ever-changing mass of ice at the bottom of the Khumbu Glacier:

As the National Geographic blog put it:

Like a gargantuan bulldozer, the Khumbu glacier plows down off the Lhotse Face between Mounts Everest and Nuptse. Dropping over a cliff just above Base Camp, this mile-wide river of ice shatters into building-size blocks and steeple-size spires called seracs. It's riven with cracks called crevasses that can be hundreds of feet deep. To reach our expedition's two goals — the Southeast Ridge and the West Ridge, which both begin atop the Khumbu glacier in the Western Cwm — we must travel up through this labyrinth of raging ice.

To cross the crevasses, you use bridges that the Sherpas have made by lashing ladders together with rope. Here's Nima Dorje Tamang crossing one. The clouds are like a ceiling... but there's no floor:

The picture above is again from National Geographic.

The glacier advances about a meter each day around here. Most climbers try to cross before the sun rises, when the cold keeps things frozen. As the intense sunlight warms things, the icefall becomes more dangerous. Blocks of ice tumble down the glacier from time to time, ranging in size from cars to houses... and sometimes entire large towers of ice collapse. They say bodies of people who die in here sometimes show up at the base of the icefall years later.

Here's Kenton Cool talking about the Khumbu Icefall. "It can implode underneath you, it can drop on you above — or god forbid, you can fall into its inner depths, never to be seen again."

And this is photographer Leo Dickinson speaking about the dangers of this place. Look at the fellow poking at snow with a pick around 0:58, revealing that it would be deadly to step there!

But suppose you succeed in crossing the Khumbu Icefall — including the last crevasse, shown in this photo by Olaf Rieck:

Then you have reached the Western Cwm, also known as the Valley of Silence:

In the middle background is Lhotse. At far right you see a bit of Nuptse. And at left there's Sāgārmatha, also known in Tibetan as Chomolungma... or in English, Mount Everest.

'Cwm', pronounced 'coom', is Welsh for a bowl shaped valley, also known as a 'cirque'. This one is a 4-kilometer-long valley carved out by the Khumbu Glacier, which starts at the base of Lhotse. It's the easiest way to approach Everest from the southeast. However, it's cut by massive crevasses that bar entrance to the upper part: here you must cross to the far right, over to the base of Nuptse, and through a narrow passageway known as the Nuptse corner.

It's called the Valley of Silence because it's often windless and deathly quiet. On days like that, the surrounding snow-covered slopes surrounding are so bright that the valley becomes a kind of solar oven, with temperatures soaring to 35 °C (95 °F) despite an elevation of 6000 to 6800 metres (19,600-22,300 feet). But when sun turns to shade, the temperature can plummet to below freezing in minutes!

The photo above was taken by the Moving Mountains Trust. See the people? You may need to click for a bigger version! For more, see:

• Alan Arnette, Life in the Western Cwm.

Want to go further? When you've reached Base Camp II near the top of the Western Cwm, you still have 2300 meters to climb... and now it gets steep! I'm sorry, I'm quitting here and heading back down — it's my bedtime. Good luck!

We can cut our carbon footprint if we travel virtually:

• Mount Everest summit—interactive 360 degree panorama.

• Reality Maps viewer for Everest.

Michael Murphy writes:

I had become intrigued by the story of Marco Siffredi, a French snowboarder who was the first to successfully descend Everest on a snowboard via the Norton Couloir. His second attempt to descend a far more serious route, the Hornbein Couloir ended in his demise.Here's the video of him leaving the summit. I used Reality Maps to trace his route. It is no wonder he did not make it.

© 2012 John Baez

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu