This red giant star, called U Camelopardalis, is 1500 light years away. Every few ten thousand years or so, a layer of helium surrounding its core gets compressed enough to undergo nuclear fusion. It does this abruptly, exploding in a helium shell flash. When this happens, the star puffs out gas and dust, as shown here. Then the helium shell sinks back down... and eventually the cycle repeats itself.

The star itself is actually less than one pixel in size: it's just so bright that it overwhelmed the device used to make this picture. The cool-looking lines coming out of the star are also, sadly, just artifacts. But the sphere of dust is real. A lot of this stuff is carbon, so U Camelopardalis is called a carbon star.

The picture is from NASA. This paper has more details:

Until now, I thought all elements heavier than iron were made by supernovae. But now I read:

Nucleosynthesis in He-shell flashes accounts for the production of about half of the heavy elements (above Fe) found on our planet. The nucleosynthesis products from the repeatedly exploding He-layer are convectively mixed into the outer layers of the star, from where they are blown off into space, ready to form new stars and planets.

How many hills are there in the British Isles? This is an ambiguous question, even after you decide how tall a 'hill' has to be. After all, what looks like one hill from afar might look like two or more when you're close. But the British love precision, so they've figured out a way to make this question precise.

First, don't count hills according to the height of the peak: that's hopeless. Count them according to prominence. A hill has prominence 10 meters, for example, if it's 10 meters taller than the lowest contour line that encircles it but no higher summit. Get it? Think about why this is more practical than counting hills by height!

Then, go ahead and count all hills (and mountains) with prominence greater than some arbitrary height... say, 150 meters.

In fact a 'Marilyn' is defined to be a mountain or hill in the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland or Isle of Man with a prominence of at least 150 meters. This is something you can count. And indeed, there are 2,009 Marilyns, shown in the map above — and carefully tabulated in Alan Dawson's best-seller The Relative Hills of Britain.

Puzzle: Why are Marilyns called 'Marilyns'?

Or if that's too hard:

Puzzle: What is the difference between the British Isles and 'the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and Isle of Man'?

Some Marilyns are harder to climb than others. Two of them are sea stacks: huge rocks jutting up from the ocean. They're called Stac an Armin and Stac Lee. In his book Relative Hills of Britain, Dawson writes:

These stacks will look absolutely frightening to most walkers. They have been climbed on several occasions, by some of the inhabitants of St Kilda before its evacuation in 1930, and by rock climbers since then, but there is no easy route up either of them. Even landing is a problem, as the stacks have no beach or cove, and calm seas are a rarity in this part of the world. Once on the stacks the multitude of seabirds on the narrow ledges are likely to pose an additional hazard.The above picture of Stac an Armin makes it clear: this is not your typical hill! Its location makes it even harder to climb. Northwest of Scotland you'll find the Outer Hebrides, a bunch of islands with a reputation for being cold, windy and remote. Some of them are big. But further east you'll see a small archipelago called St. Kilda, whose population has been evacuated. It contains a tiny island called Hirta, which is now a missile base. North of that you'll see an even tinier island called Boreray, which is uninhabited. And northwest of that is Stac an Armin! To the southwest is Stac Lee.

You can see Stac Lee at the right in the picture above. Boreray is in the background, and Stac an Armin is the big thing in front.

For a great tale, with pictures, written by someone who climbed Boreray, try this:

July 11, 2012

On July 9th I posed this puzzle:

Puzzle: What is the difference between the British Isles and 'the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and Isle of Man'?

The answer is clear from this chart taken from Wikipedia:

For years I found the definitions of all these concepts very confusing, and that's not even counting 'Britain' — or the 'Commonwealth', which now even includes Rwanda. Do all empires develop complicated Venn diagrams like this showing degrees of partial membership, or is it an especially British thing?

Wow! Brian Eno's first full-fledged ambient album, Discreet Music, is now free online!

Eno got the idea for this while lying in bed, recovering from being hit by a car. On the back cover, he wrote:

My friend Judy Nylon visited me and brought me a record of 18th century harp music. After she had gone, and with some considerable difficulty, I put on the record. Having laid down, I realized that the amplifier was set at an extremely low level, and that one channel of the stereo had failed completely. Since I hadn't the energy to get up and improve matters, the record played on almost inaudibly. This presented what was for me a new way of hearing music — as part of the ambience of the environment just as the color of the light and the sound of the rain were parts of that ambience.

As her name suggests, Judy Nylon was a punk rocker. It pleases me to know she'd give Eno some 18th century harp music.

The first side of the album Discreet Music was a 30-minute piece with the same name. It's wonderfully dreamy and peaceful, but it was made in a calculated way. It began with two melodic phrases of different lengths played back from a synthesizer — an EMS Synthi AKS — which had something that was unusual back in 1975: a built-in digital sequencer. This signal was then run through a graphic equalizer, which let Eno control the timbre. It was then run through an echo unit before being recorded onto a tape machine. The tape ran to the take-up reel of a second machine. The output of that machine was then fed back into the first tape machine, which recorded the overlapping signals.

The second half of the album was 'Three Variations on the Canon in D Major by Johann Pachelbel'. These pieces were performed by a string ensemble, conducted and co-arranged by Gavin Bryars. The members of the ensemble were each given brief excerpts from the score, which were repeated several times, along with instructions to gradually alter the tempo and other elements of the composition The titles of these pieces were derived from inaccurate translations of the French liner notes on a version of Pachelbel's canon performed by the orchestra of Jean Francois Paillard.

Some of my information here is paraphrased from the Wikipedia article, but I don't trust their description of the three Pachelbel pieces. so I changed those. For some amusement, look at the 'genre' label on the mp3 files of these pieces. For more music, try other albums on the same label, now free online.

Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendma was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice. At that time Macondo was a village of twenty adobe houses, built on the bank of a river of clear water that ran along a bed of polished stones, which were white and enormous, like prehistoric eggs. The world was so recent that many things lacked names, and in order to indicate them it was necessary to point.

Thus, with an bang, begins One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel Garcia Márquez. The first sentence is one of those cliffhangers that makes you read on... and it introduces the violence of Latin American military rule, and the magic of childhood. The second introduces the main character of the book: the town of Macondo. The third tells us: "I am making up a new world here, the tired rules of 'realism' don't apply, get ready for a wild ride."

I read this book a long time ago but I bought it again today just to celebrate finding a small French bookstore in Singapore. (Yes, they also sell some books in English.) If you haven't read this, I recommend it. You can read some more on the Nobel Prize website.

Imagine you're in a space ship in the very early Solar System, before planets form from the protoplanetary disk shown here. At the frost line, about where the asteroid belt will be, it gets cold enough for ice grains. When you pass this line, the density of solid particles in the disk abruptly increases by a factor of 3 or 4. So, these particles will stick together to form larger bodies—and faster, too! This means that gas giants are more likely to appear beyond the frost line, since the bodies that form beyond this line are bigger and have more time to accrete gas from the disk before it dissipates.

The frost line is also called the 'snow line', and you can read more about it here:

What would it actually look like as you approached the early Solar System? Maybe like this:

This is a protoplanetary disk called Object HH 30 in the constellation of Taurus, 450 light years away. It's about 0.006 times the mass of our Sun, and some astronomers think it may last only about 100,000 years, a blink of an eye in the world of astronomy. There's a huge jet of hot gas shooting out of the star. This is common, but we don't know how these jets are focused.

For more, see:

July 25, 2012

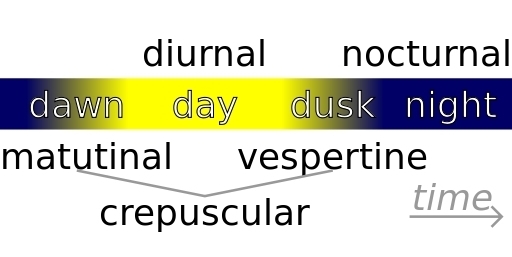

When are you most active? Are you diurnal, nocturnal, matutinal, vespertine, crepuscular... or cathemeral?

Animals used to be classified as either diurnal or nocturnal, but it's more complicated than that. Most of the words above are explained in this chart. But a cathemeral organism is one that's active at sporadic and seemingly random times during the day or night. An example is the common brown lemur.

It would also be good to have fancy words for people (and maybe animals) who are most active either from dawn to noon or from noon to dusk. Luckily, good candidate words already exist: antemeridial for before noon, and pomeridial for afternoon.

It can be said with complete confidence that any scientist at any age who wants to make important discoveries must study important problems. Dull or piffling problems yield dull or piffling answers. It is not enough that the problem should be interesting: almost any problem is interesting if it is studied in sufficient detail. - Peter Medawar

© 2012 John Baez

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu