Morgan Abbou explains:

Volcanic lightning photograph by Francisco Negroni. In a scene no human could have witnessed, an apocalyptic agglomeration of lightning bolts illuminates an ash cloud above Chile's Puyehue volcano in June 2011. The minutes-long exposure shows individual bolts as if they'd all occurred at the same moment and, due to the Earth's rotation, renders stars (left) as streaks. Lightning to the right of the ash cloud appears to have illuminated nearby clouds.hence the apparent absence of stars on that side of the picture. After an ominous series of earthquakes on the previous day, the volcano erupted that afternoon, convincing authorities to evacuate some 3,500 area residents. Eruptions over the course of the weekend resulted in heavy ashfalls, including in Argentine towns 60 miles (a hundred kilometers) away.

Here's another shot of the same volcano:

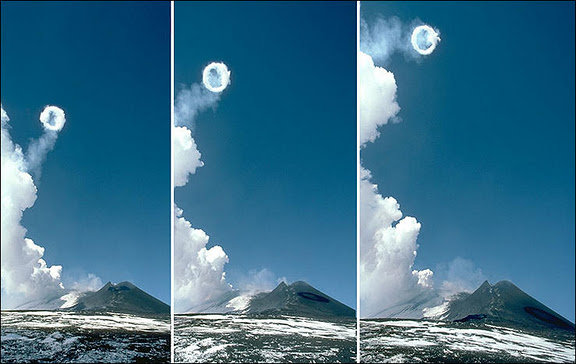

And here's Mount Etna blowing out a smoke ring in March of 2000:

By its shadow, the ring was estimated to be 200 meters in diameter!

November 5, 2011

I've been spending less time on this diary and lots of time sharing

similar tidbits of information on Google+. The quick feedback from other

people is addictive, and lots of people seem to be paying (at least a

little) attention. Here's the number of people who have me in their circles,

from when I started to today:

According to the CircleCount website, I have 4872 people following me today, putting me at the 3,271st most popular of 5,660,375 people on Google+ that they've indexed.

Now, on with some of my favorite music! I'm posting these items on Google+, but copying them here...

November 6, 2011

Going further back into Eno's catalog, my friends and I got Eno's first solo album, Here Come the Warm Jets.

From the title, you might think "Baby's on Fire" is a typical rock song about passionate lust, but no! Amid a strange chirping of synthesizers and moaning of guitar, Eno launches into his tale in a rather unfriendly and whiny voice, and you soon realize he means it quite literally:

Thus begins the fiery theme we hear later in songs like "Third Uncle" - remember burn my uncle, burn his books? - and "Burning Airlines Give You So Much More". Soon Robert Fripp enters with the incendiary guitar work that's the real point of this song. He builds up a lot of tension atop the rather static background, dominated by those endlessly chirping synths and repetitive high-hat cymbal. Then Eno returns and leaves us with a warning:

and the song screeches to a halt, like a train slamming on the brakes and shooting out sparks. (If you've been paying attention, that should remind you of "China My China".)

If you like this song and have never heard the live version by his band 801, try this:

It has Manzanera rather than Fripp on guitar. Eno became famous for avoiding live performances and staying in the studio, but 801 could really rock, and their 1976 album 801 Live is definitely worthwhile. According to Wikipedia, it

... set new standards for live recordings because it was one of the first live LPs in which all outputs from the vocal microphones, guitar amps and others instruments (except the drums) were fed directly to the mobile studio mixing desk, rather than being recorded via microphones and/or signals fed out the front-of-house PA mixer.

Note also how the applause at the end is fed through a phase-shifter!

Why 801? Well, the line "we are the 801" appears in the song "The True Wheel" on Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy), but you also can't help noticing that in British English, you might say it like this: Eight Nought One.

"Dead Finks Don't Talk" is another song from the same album. It's one of Eno's silliest, but a universe without it would be missing something crucial: as soon as I heard it, I realized that.

Here Come the Warm Jets was recorded in twelve days at Majestic Studios in London, most of it during September 1973. Besides Eno, sixteen musicians played on the album, including John Wetton and Robert Fripp of King Crimson, Simon King from Hawkwind, Bill MacCormick of Matching Mole, Paul Rudolph of Pink Fairies, Chris Spedding on guitar, and everyone in Eno's earlier band Roxy Music except vocalist Bryan Ferry, whose florid style Eno mimics here when he sings:

Eno selected them on the basis that he thought they were incompatible with each other musically. He said he "got them together merely because I wanted to see what happens when you combine different identities like that and allow them to compete.... [The situation] is organized with the knowledge that there might be accidents, accidents which will be more interesting than what I had intended." He directed the musicians with the help of body language and dancing.

November 6, 2011

Returning to the 'present' in my tale — 1979, my last year of high school — another album that made a huge impact was Fear of Music by Talking Heads.

Already from the title and the cover — textured like a manhole cover — it was clear that this was some strange new kind of music. On many songs, like this, David Byrne's voice quivers with an emotion we hadn't heard much in rock before: nervous fear, verging on paranoid breakdown!

It's funny, of course — but he sounds like he really means it.

The music is tight, disciplined, metallic. Avoiding traditional forms, the songs come in blocks of solid contrasting texture, cutting from one to another abruptly This one comes in two completely different parts, each with a tricky rhythmic structure — so tricky, in fact, that they hardly ever played this one live.

Robert Christgau, writing in The Village Voice, praised this album's "gritty weirdness", but claimed that "a little sweetening might help". In fact the uncompromising nature of Fear of Music the lack of "sweetening", is what makes it great.

Many rock songs glamorize psychedelic drugs, but rather fewer try hard to realistically portray their effect. On Fear of Music, the Talking Heads take a stab at it — and Byrne being the nervous fellow he was, it shouldn't be surprising that it's a bad trip. But a great song!

Here the sonic wizardry of Brian Eno, the producer of this album, comes in handy. The song starts with a faint haze of bird songs echoing off the hard walls of a zoo — at least that's what it sounds like. That pulls your attention in. Then comes a heavy bass melody by Tina Weymouth — the melody that really defines the song — along with drums by Chris Frantz, some eerie whooshing sounds, and a little guitar lick by Byrne, consisting of a note repeated 5 times. All this then repeats, with a little development... and amazingly, it carries us almost one minute through this song. Then at 0:57 there's a dramatic transformation: the music switches from "heavy" to "spacy", with synthesizers, probably played by Jerry Harrison, and heavily processed voices floating in a spacious blur: lots of echo to make the space seem big. The bass line continues unperturbed; in fact, if you analyze this song you'll see it's basically a blues, despite all the unusual features!

Then at 1:18 we go back to the "heavy" section, the space collapsing back down to claustrophobic tightness. The singing starts at 1:21 with Byrne rapidly exhaling... then anxiously proclaiming:

The last word is echoed 5 times (no coincidence, that number), with each echo just as loud as the original: one of many disorienting effects on this track.

I won't go on in such detail, though it'd be fun (for me at least). I'll just point out the scary backwards echo at 3:00, which seems to jump out of the speakers... the way the reverb on Byrne's voice completely drops out at 3:42, making him seem much closer all of a sudden as he lets out a little apologetic laugh... the odd vocal sounds that kick in at 3:56... and the crazy, fractured guitar solo — probably chopped to pieces by splicing bits of tape — that ends the song in one of those marvelous fades that leave you cranking up the volume to hear every last bit. (At end, you'll hear those birds again.)

In short it's a meticulously composed piece, and it's that blend of craft and craziness that makes Fear of Music so fun.

November 7, 2011

How should a song end? Only with recorded music did gradually fading out while repeating become popular. Music theorist Richard Middleton wrote:

At the meta-song level, the prevalence of pre-taped sequences (for shops, pubs, parties, concert intervals, aircraft headsets) emphasizes the importance of flow. The effect on radio pop programme form is a stress on continuity achieved through the use of fades, voice-over links, twin-turntable mixing and connecting jingles.

This song "Cities" does something rarer: it fades in, with siren-like sounds mixed with a driving beat conveying the hectic rush of city life. It also fades out at the end, with Byrne repeating:

in ever more crazed ways. A good fade-out makes you want to hear every last little bit, and this one rewards you if you do: by the end, Byrne's gibbering madness completely belies his earlier observation:

The song is remarkably homogeneous throughout, and instead of the guitar carrying the main melody, it's a repetitive bass line by Tina Weymouth that does the job! Byrne's guitar provides percussion instead, mimicking the rhythm of his vocal lines — with the exception of a short solo starting at 1:43. And Eno and Harrison add dashes of color here and there to keep things exciting... for example, complicated little metallic clanking patterns in the background, noticeable especially around 2:37. These layers of subtlety help make the song fun to listen to over and over.

Finally, a puzzle: why does Byrne say this?

There's an easy part to this question, and a hard part.

November 8, 2011

This is a live version of the Talking Heads song "Cities" from 1980, one year after Fear of Music came out. It's from the concert tour for their next album, Remain in Light. So, besides the basic band, the lineup includes Adrian Belew on guitar, Dolette McDonald on vocals, Steve Scales on percussion, Burnie Worrell on keyboards, and Busta Jones on bass. Some of these musicians can be heard on Remain in Light; others appear on the Heads' next album Speaking in Tongues, or the intervening solo projects: David Byrne's The Catherine Wheel, Jerry Harrison's The Red and the Black, and Chris Frantz and Tina Weymouth's Tom Tom Club.

In this later era, the Heads' music became less paranoid, more ecstatic. You can see the extra band members are having lots of fun. Adrian Belew, in particular, is a happy hambone. See him wave to the crowd right before the song starts?

The camera work in this video is inane — for example, watch how it lingers on Tina's legs starting at 4:53. Someone on Google+ suggests that this was because it was made for an Italian TV show. For a version with better camera work but worse sound, try their show in Germany:

And from the same show in Rome, here's the song "Drugs":

Here you can really see Belew's guitar abilities put into play - he makes plenty of psychedelic sounds to make up for the missing studio effects, and throws some great middle-eastern melodies into his final solo.

However, the wonderfully ominous feel of the original is gone. For one thing, the tempo has been sped up. For another, it's been given a more funky vibe, thanks in part to Busta Jones on bass and Steve Scales on percussion. So, while it's great fun, it's really a different song. It doesn't mess with your mind in the same carefully crafted way.

By the way, you can get very nicely recorded versions of the songs on this tour on the live album The Name of This Band is Talking Heads.

November 9, 2011

The first track on Fear of Music is different from the rest! It's the only really happy song on the album, and it points to the future of the Talking Heads, where their nervous energy got transformed into ecstatic dance. Later, Jerry Harrison said:

We also knew that our next album would be a further exploration of what we had begun with "I Zimbra".

So here it goes! First a high-pitched guitar picking out a light repetitive melody atop cymbals and two conga tracks — one for each ear! Then the bass enters along with a new guitar, and that high-pitched guitar drops out. Then another guitar comes in, building up the energy. The patterns change a bit when the lyrics arrive, sung en masse by Byrne, Harrison, Weymouth and a guest vocalist:

Bim blassa galassasa zimbrabim

Blassa glallassasa zimbrabim

A bim beri glassala grandrid

E glassala tuffm i zimbra

Then comes a break at 1:19: space opens up, that little high-pitched guitar melody returns at 1:37, and things build up much as they did at the song's beginning...

... but this time, the guitar of Robert Fripp enters, with an almost accordion-like timbre, playing a devilishly slippery melody in 8/4 time! No live version pleases me as much as this recorded version, because no guitarist can play like Fripp.

Then the chorus returns, just like the beginning, but now atop Fripp's guitar:

Then that little high-pitched guitar melody... the same build-up.... but now a return of Fripp.... all building up to a graceful climax and a sudden end.

The lyrics were based on a poem by the Hugo Ball, one of the founders of Dadaism, who started the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich in 1916 — an artistic nightclub where Kandinsky, Klee, de Chirico, and Max Ernst hung out.

The song also features the Egyptian musician Hossam Ramzy on surdo (a kind of bass drum), Abdou M'Boup on djembe and talking drum, and Assane Thiam playing some other percussion... but my ears can't pick them out; maybe I'm mixing them up with the congas.

And guess who's playing those congas? The German punk singer Ari Up, and... Gene Wilder!

By the way, after you listen to this while reading the lyrics and my description, you can have some more fun listening to it while focusing your full attention on the bass. You'll see how disciplined Tina Weymouth is: not a virtuoso, but every note just right, and no pointless screwing around. Rock solid. That's what makes you want to dance.

This live performance of "I Zimbra" by David Byrne is definitely worth a listen:

I don't like how the music drops to a crawl at 2:09 — I think of this song as a single energetic blast — but it's nice to see that 19 years later, he could still belt out those lyrics!

November 14, 2011

Back in 2007 I found myself mysteriously intrigued by images of ice and the idea of coldness, both literal and metaphorical. I felt the need to make some art and music on these themes. So, I made an album called Glacial. After a while, just as mysteriously, this desire left.

The pieces on Glacial are in a Dorian mode. Just as an upside-down smile is a frown, turning the major scale upside down gives a minor scale. But when you turn the Dorian mode upside down, you get the Dorian mode again. This may account for its emotionally netural quality — a quality I used to convey the cold indifference of a glacial landscape.

Kangerdlugssuaq is the largest glacier on the east coast of the Greenland ice sheet. "Kangerdlugssuaq" is also the title of the first piece on my album. You can hear or download it by clicking on this picture:

"Sermersuaq" digs deeper into this glacial theme. To create it, I took some fragments of sound that didn't find their way into the first piece, and expanded them to form a piece that sounds like it was taped in an ice cave as massive floes were grinding against each other. You can listen to it here:

In real life, Sermersuaq is in northwestern Greenland. Stretching 90 kilometers across, it's the Northern Hemisphere's widest tidewater glacier: a glacier that begins on land, but terminates in water.

This piece was influenced by Thomas Köner's chilly, minimalist Permafrost. The pieces on that album have frigid titles like "Nival", "Serac", and "Firn" (all snow and ice formations)... and they're scarily empty, like an Arctic landscape. I'm happy to report that it's now available on SoundCloud.

The third and final piece on Glacial is called "pujuq kanirnartuq":

It's even colder and darker: an icy mist at twilight. Best listened to on speakers with powerful bass.

You may have heard the Eskimo have a hundred words for snow. That's a bit misleading — more on that later — and they don't like being called "Eskimo" either. But unsurprisingly, the Inuit do have quite a few words for phenomena involving ice, snow and the like, and pujuq kanirnartuq is the term for "frozen mist" in the language Kalaallisut, also known as West Greenlandic.

Here's a word list taken from Fortescue's text on Kalaallisut:

You've probably heard that the Eskimos have lots of words for snow — and maybe you've heard other people say no, that's not true. But the whole dispute seems a bit silly when you find out that the Eskimo — or more precisely, the speakers of West Greenlandic — have a word for "once again they tried to build a giant radio station, but it was apparently only on the drawing board." It's

West Greenlandic is also known as Kalaallisut: it's the main Inuit language spoken in Greenland:

I know practically nothing about the Inuit languages, but I enjoyed this piece:

It's about Inuktitut, the name for some members of this language group spoken in Eastern Canada. It's pretty technical, so let me just give you a taste.

Verbs can be singular, dual, or plural:

takujunga — I see

takujuguk — we two see

takujugut — we several see

Instead of using words like "because", "if" or "whether" they use different verb endings:

takugama — because I see

takugunnuk — if we two see

takungmangaatta — whether we several see

They can also attach the object of the verb:

takujagit — I see you

takujara — I see him

takugakku — because I see him

But there are also suffixes that turn verbs to nouns, and suffixes that turn nouns to verbs... and you can use both in a single complicated word! There are ways to indicate whether something is stationary or moving, expected or unexpected:

tavva! — Here it is! (stationary and expected)

avva! — There it is over there! (mobile and unexpected)

There are ways to add spatial information:

tavvani — at this (expected) spot

maangat — from this (unexpected) area

tappaunga — to that (expected) area up there

kanuuna — through that (unexpected) spot down there

And all this is just scratching the surface! So in a typical written text, only a minority of words are ever repeated.

© 2011 John Baez

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu