Here is Lisa with a neighborhood cat that we love, named Frenchie.

When it sees us it meows, comes running, and then slides down the dirt

on its back, eager to be petted.

February 12, 2021

This is one of our other favorite neighborhood cats, named Tee.

It showed up at a neighbor's house and hangs out there, but they

don't exactly own it.

February 13, 2021

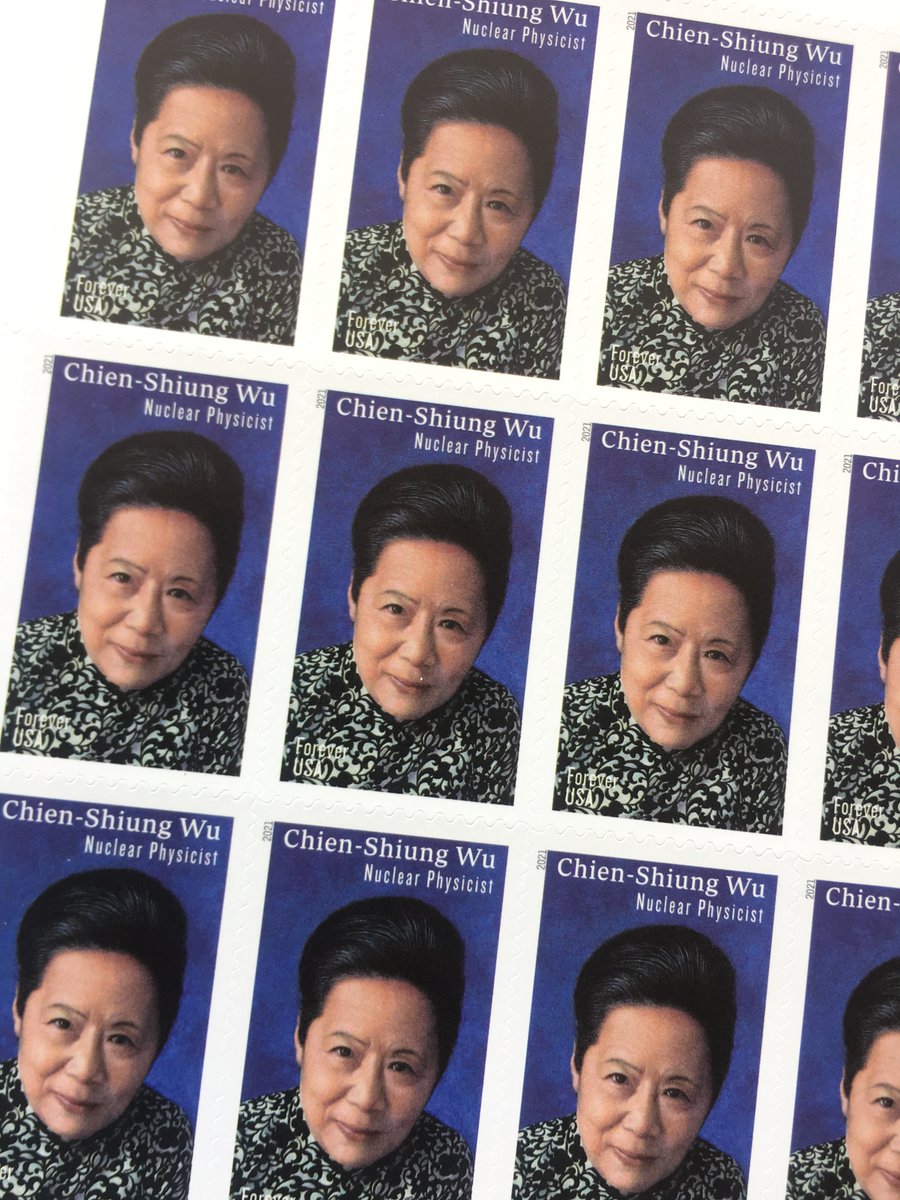

Yay! The US now has a stamp honoring Chien-Shiung Wu, the physicist who did one of the most fundamental experiments possible: she discovered that the laws of nature distinguish between right and left!

Two men got the Nobel prize for this, not her.

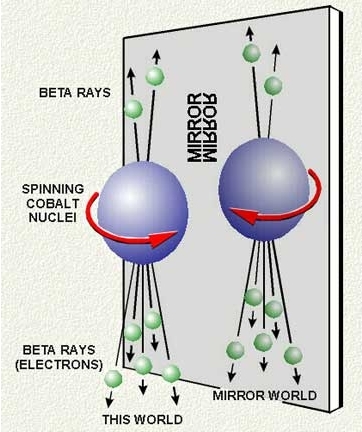

Yes, she showed that a spinning radioactive cobalt-60 nucleus is a bit more likely to shoot electrons out one end than the other. So, the basic laws of physics are different here than they would be in a mirror image world.

She did this experiment in 1956:

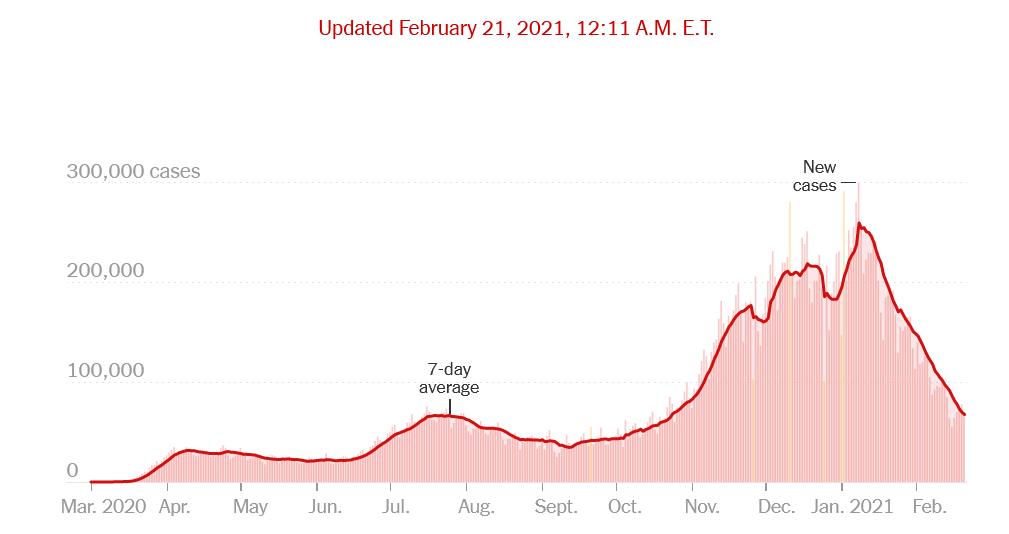

Some blame climate change, but the power industry in Texas, and the government there, seem to be a lot of the problem — since other states, just as cold, are doing much better.

A Glimpse of America’s Future: Climate Change Means Trouble for Power Grids

Brad Plumer, Washington Post, February 16, 2021

Huge winter storms plunged large parts of the central and southern United States into an energy crisis this week, with frigid blasts of Arctic weather crippling electric grids and leaving millions of Americans without power amid dangerously cold temperatures.The grid failures were most severe in Texas, where more than four million people woke up Tuesday morning to rolling blackouts. Separate regional grids in the Southwest and Midwest also faced serious strain. As of Tuesday afternoon, at least 23 people nationwide had died in the storm or its aftermath.

Analysts have begun to identify key factors behind the grid failures in Texas. Record-breaking cold weather spurred residents to crank up their electric heaters and pushed power demand beyond the worst-case scenarios that grid operators had planned for. At the same time, a large fraction of the state’s gas-fired power plants were knocked offline amid icy conditions, with some plants suffering fuel shortages as natural gas demand spiked. Many of Texas’ wind turbines also froze and stopped working.

The crisis sounded an alarm for power systems throughout the country. Electric grids can be engineered to handle a wide range of severe conditions — as long as grid operators can reliably predict the dangers ahead. But as climate change accelerates, many electric grids will face extreme weather events that go far beyond the historical conditions those systems were designed for, putting them at risk of catastrophic failure.

[...]

Texas’ grid operators had anticipated that, in the worst case, the state would use 67 gigawatts of electricity during the winter peak. But by Sunday evening, power demand had surged past that level [to 69 gigawatts]. As temperatures dropped, many homes were relying on older, inefficient electric heaters that consume more power.

The problems compounded from there, with frigid weather on Monday disabling power plants with capacity totaling more than 30 gigawatts. The vast majority of those failures occurred at thermal power plants, like natural gas generators, as plummeting temperatures paralyzed plant equipment and soaring demand for natural gas left some plants struggling to obtain sufficient fuel. A number of the state’s power plants were also offline for scheduled maintenance in preparation for the summer peak.

The state’s fleet of wind farms also lost up to 4.5 gigawatts of capacity at times, as many turbines stopped working in cold and icy conditions, though this was a smaller part of the problem.

Once when I was young my parents drove us to Skyline Drive and Luray Caverns. And in junior high school, one summer I went to camp at the Burgundy Center for Wildlife Studies, in West Virginia. But that's about all.

To feed my fantasies, I just bought this book:

These are mountains of many names. The chain as a whole is referred to as the Appalachians, but there are dozens of smaller, discreet mountain systems contained within it. Some, like the Great Smokies in the south and the White or Green mountains in New England, are famous in their own right, but others are little known outside their own shadows. For me, their names are magically evocative: the Black Mountains, the Unakas, the Shickshocks, the Notre Dames, the Unicois, the Snowbirds, the Cold Hollow Hills. All ring with mysteries, and all hold secrets. They comprise a land with an uncanny ability to hold the human spirit — the mountains of the heart.

It's less catchy and more repetitive than some of Bach's more famous keyboard music, but Anderszewski gives it a propulsive energy that's quite absorbing. I may get the album this comes from, which contains the First, Third and Fifth of the English Suites.

Here's a review on Gramophone:

This is a glorious disc. Simply glorious. Anderszewski and Bach have long been congenial bedfellows and the Pole’s playing here is compelling on many different levels. To start with, there’s the sense of sharing the sheer physical thrill of Bach’s keyboard-writing. This is particularly evident in faster movements such as the fierce and brilliant fugal Gigue that concludes the Third Suite, or, in the E minor Fifth Suite, the extended fugal Prelude and the outer sections of its Passepied I. Common to all is a sense of being fleet but never breathless, with time enough for textures to tell.I should read this:At every turn you get the sense of Bach flexing his compositional muscles in these early keyboard suites. There is of course nothing innately ‘English’ about them and the origin of their title is shrouded in mystery, though Bach’s earliest biographer Johann Nikolaus Forkel speculated that it reflected the nationality of the suites’ (unknown) dedicatee. As with the keyboard partitas (of which Anderszewski so memorably recorded the First, Third and Sixth for Virgin Classics back in 2001 – 1/03), there’s a sense of Bach demonstrating just how much variety he could introduce into a suite built around the common elements of Prelude, Allemande, Courante, Sarabande and Gigue. In Anderszewski’s hands the First, Third and Fifth very much occupy their own worlds in terms of mood. Thus there’s a palpable delight in the rhythmically ungainly theme from which the Gigue of the First Suite is fashioned and Anderszewski’s way with Bach’s counterpoint is at once strong-jawed and supple. We’re always aware of the re entry of a fugue subject, for instance, as it peeks through the texture in different registers or reappears stood on its head, yet it’s never exaggerated as is sometimes the tendency with less imaginative pianists.

And how Anderszewski can dance — at least at the keyboard — in a movement such as the Prelude of the Third Suite, urged into life through subtle dynamics, voicings, articulation and judicious ornamentation. A very different kind of dance reveals itself in the Gavotte II of the Third Suite, a musette in which he takes a more impish view than many, the sonorous drone effect contrasting delightfully with the tripping upper lines. The way he has considered the touch and dynamic of every phrase means that these are readings that constantly impress with fresh details each time you hear them.

Even the most apparently unassuming numbers, such as the Second Bourrée of the First Suite or the Passepied II of the Fifth, gain a sense of intrigue as he re examines them from every angle, again bringing multifarious shadings to the music. And it all flows effortlessly — though I’m sure the journey has been anything but that. Highlights abound: in the murmuring Courante of the Third Suite, the Pole’s reactivity leaves Maria João Pires sounding a touch unsubtle — which is really saying something. This is followed by one of the most extraordinary readings of the Sarabande I’ve ever heard. While Pires revels in its echoing harmonies, Anderszewski draws you daringly into his own world, as Bach’s initially grandiose sonorities become more and more withdrawn. This whispered intimacy extends into his insertion of an ornamented version of this movement, entitled ‘Les agréments de la même Sarabande’, which proves a masterclass in audacious ornamentation, yet never overburdening Bach’s melodic lines. In fact the effect here is truly meditative. Fittingly, there is a long silence before the limpid Gavotte.

Are there any caveats? Some might find the basic pulse of the First and Fifth Sarabandes perhaps too slow. To me they work precisely because he teases so much out of each line. They have a Gouldian intensity that draws you ineluctably in without any of the Canadian’s wilfulness.

You can be in no doubt of the thought that has gone into this enterprise, from Anderszewski’s ordering of the courantes of the First Suite, which he explains in the booklet, to the programming of the suites themselves, opening the disc with the Third rather than the more quizzical First. And at every turn, he harnesses the possibilities of the piano in the service of Bach; the result is a clear labour of love, and one in which he shines new light on old music to mesmerising effect, all of which is captured by a warmly sympathetic recording and an engaging booklet-note by Mark Audus.

Anderszewski’s CDs are all too infrequent, so let’s cherish this one.

This coastal area could be one of the routes people took from Siberia into the Americas. Folks have recently become convinced that wolves were first tamed in Siberia. But this line of dogs may have separated from the Siberian line for 6,550 years! And by isotope analysis of the bones, it seems this particular dog may have subsisted on a diet of fish and scraps from seals and whales.

Here's a nice article about this research:

And here's the actual research:

Red foxes colonised the North American continent in two waves: before or during the Illinoian glaciation, and during the Wisconsinan glaciation. Gene mapping demonstrates that red foxes in North America have been isolated from their Old World counterparts for over 400,000 years, thus raising the possibility that speciation has occurred, and that the previous binomial name of Vulpes fulva may be valid.The Wisconinan glaciation was the last 'ice age' — or technically 'glaciation' — and the Illinoian was the one before that, roughly 190,000-130,000 years ago. There have been lots of glaciations in the last few million years. It sounds like foxes may have come over here just in the last two! But I'm a bit confused, because it also sounds like they also genetically separated from old world foxes 400,000 years ago. Maybe they were hanging out in Siberia or something....[....]

Although they ranged far south during the Wisconsinan, the onset of warm conditions shrank their range toward the north, and they have only recently reclaimed their former American ranges because of human-induced environmental changes. Genetic testing indicates two distinct red fox refugia exist in North America, which have been separated since the Wisconsinan.