|

|

|

Here's a game. I flip a fair coin. If it lands heads up, I give you $1. If it lands tails up, I give you nothing.

How much should you pay to play this game?

This is not a mathematics question, because it asks what you "should" do. This could depend on many things that aren't stated in the question.

Nonetheless, mathematicians have a way they like to answer this question. They do it by computing the so-called 'expected value' of your payoff. With probability 1/2 you get 1 dollar; with probability 1/2 you get 0 dollars. So, the expected value is defined to be

Don't be fooled by the word 'expected': mathematicians use words in funny ways. I'm not saying you should expect to get 1/2 a dollar each time you play this game: obviously you don't! It means that you get 1/2 a dollar 'on average'. More precisely: if you play the game lots of times, say a million times, there's a high probability that you'll get fairly close to 1/2 a million dollars. (We could make this more precise and prove it, but that would be quite a digression right now.)

So, if you have lots of money and lots of time, you could pay up to 1/2 a dollar to play this game, over and over, and still make money on average. If you pay exactly 1/2 a dollar you won't make money on average, but you won't lose it either—on average.

Let's make the idea precise:

Definition. Suppose \( X\) is a finite set and \( p\) is a probability distribution on that set. Suppose

is a function from \( X\) to \( \mathbb{R}.\) Then the expected value of \( f\) with respect to \( p\) is defined to be

The idea here is that we are averaging the different values \( f(i)\) of the function \( f\), but we count \( f(i)\) more when the probability of the outcome \( i\) is bigger. We pronounce \( \langle f \rangle\) like this: "the expected value of \( f\)".

Example 1. Suppose you enter a lottery have a 0.01% chance of winning $100 and a 99.99% chance of winning nothing. What is the expected value of your payoff?

With probability 0.0001 you win $100. With probability .9999 you win zero dollars. So, your expected payoff is

dollars. So: if you play this game over and over, you expect that on average you will win a penny per game.

But usually you have to pay to enter a lottery! This changes everything. Let's see how:

Example 2. Suppose you pay \(\$\)5 to enter a lottery. Suppose you have a 0.01% chance of winning \(\$\)100 and a 99.99% chance of winning nothing. What is the expected value of your payoff, including your winnings but also the money you paid?

With probability 0.0001 you win \(\$\)100, but pay \(\$\)5, so your payoff is \(\$\)95 in this case. With probability .9999 you win nothing, but pay \(\$\)5, so your payoff is -\(\$\)5 in this case. So, your expected payoff is

dollars. In simple terms: if we play this game over and over, we expect that on average we will lose \(\$\)4.99 per play.

Example 3. Suppose you pay \(\$\)5 to play a game where you flip a coin 5 times. Suppose the coin is fair and the flips are independent. If the coin lands heads up every time, you win \(\$\)100. Otherwise you win nothing. What is the expected value of your payoff, including your winnings but also the money you paid?

Since the coin flips are fair and independent, the probability that it lands heads up every time is

So, when we count the \(\$\)5 you pay to play, with probability 1/32 your payoff is \(\$\)95, and with probability (1 - 1/32) = 31/32 your payoff is -\(\$\)5. The expected value of your payoff is thus

dollars.

Soon we'll start talking about games where players used 'mixed strategies', meaning that they randomly make their choices according to some probability distribution. To keep the math simple, we will assume our 'rational agents' want to maximize the expected value of their payoff.

But it's important to remember that life is not really so simple, especially if payoffs are measured in dollars. Rational agents may have good reasons to do something else!

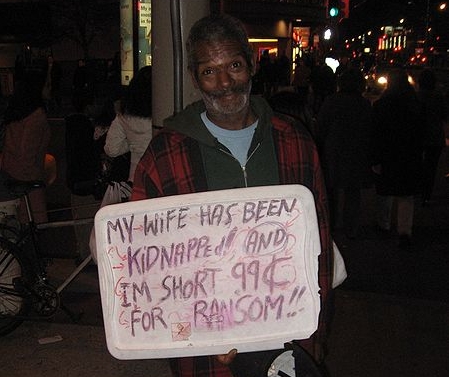

For example, suppose some evil fiend says they've kidnapped my wife and they'll kill her unless I give him a dollar. Suppose I only have 99 cents. But suppose they offer me a chance to play this game: I flip a fair coin, and if it lands heads up, I get \(\$\)1. If it lands tails up, I get nothing.

How much would I pay to play this game?

Assuming I had no way to call the police, etcetera, I would pay all my 99 cents to play this game. After all, if I don't play it, my wife will die! But if I do play it, I would at least have a 50% chance of saving her.

The point here is that my happiness, or utility, is not proportional to my amount of money. If I have less than \(\$\)1, I'm really miserable. If I have \(\$\)1 or more, I'm much better off. There are many other reasons why people might be willing to pay more or less to play a game than the expected value of its monetary payoff. Some people are risk tolerant: they are willing to accept higher risks to get a chance at a higher payoffs. Others are risk averse: they would prefer to have a high probability of getting a payoff even if it's not so big. See:

• Risk aversion, Wikipedia.

In class I asked all the students: would you like to play the following game? I'll flip a fair coin. Then I'll double your quiz score for today if it comes heads, but give you a zero for your quiz score if it comes up tails.

Suppose your quiz score is \( Q.\) If you get heads, I'll give you \( Q\) more points. If you get tails, I'll take away \( Q\) points. So the expected value of the payoff for this game, measured in points, is

So, if the expected value is what matters to you, you'll be right on the brink of wanting to play this game: it doesn't help you, and it doesn't hurt you.

But in reality, different people will make different decisions. I polled the students, using our electronic clicker system, and 46% said they wanted to play this game. 54% said they did not.

Then I changed the game. I said that I would roll a fair 6-sided die. If a 6 came up, I would multiply their quiz score by 6. Otherwise I would set their quiz score to zero.

If your quiz score is \( Q\), your payoff if you win will be \( 5 Q\), since I'm multiplying your score by 6. If you lose, your payoff will be \( -Q.\) So, the expected value of your payoff is still zero:

But now the stakes are higher, in a certain sense. You can win more, but it's less likely.

Only 30% of students wanted to play this new game, while 70% said they would not.

I got the students who wanted to play to hand in slips of paper with their names on them. I put them in a hat and had a student randomly choose one. The winner got to play this game. He rolled a 1. So, his quiz score for the day went to zero.

Ouch!

Here is a famous beggar in San Francisco:

You can also read comments on Azimuth, and make your own comments or ask questions there!

|

|

|