I'd like to tell you about two kinds of logic. In both, we start with a set \\( X \\) of "states of the world" and build a set of statements about the world, also known as "propositions". In the first, propositions correspond to subsets of \\( X \\). In the second, propositions correspond to partitions of \\( X \\). In both approaches we get a _poset_ of propositions where the partial order is "implication", written \\( \implies \\).

The first kind of logic is very familiar. We could call it "subset logic", but it's part of what people usually call "[classical logic](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Classical_logic)". This is the sort of logic we learn in school, assuming we learn any at all. The second kind of logic is less well known: it's called "[partition logic](https://arxiv.org/abs/0902.1950)". Interestingly, Fong and Spivak spend more time on the second kind.

I'll start by talking about the first kind.

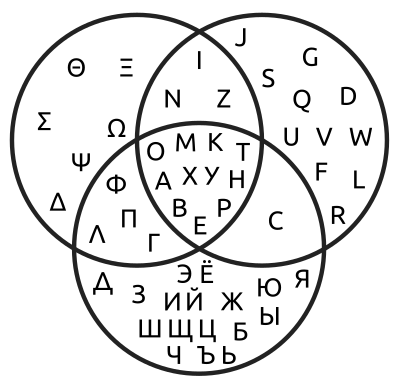

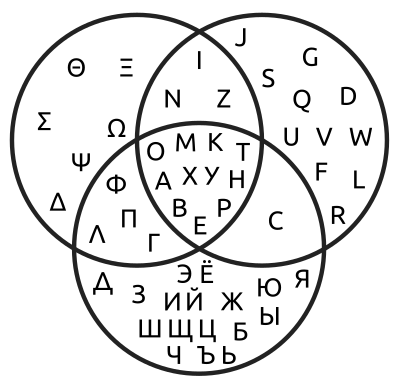

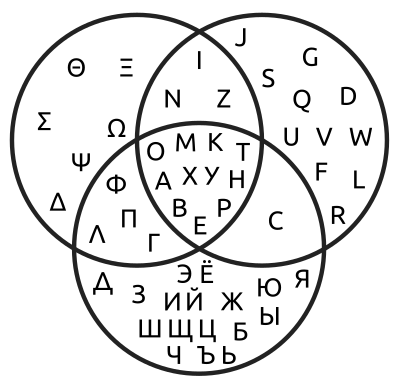

Most of us learn the relation between propositions and subsets, at least implicitly, when we meet [Venn diagrams](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venn_diagram):

This is a picture of some set \\( X \\) of "states of the world". But the world here is very tiny: it's just a letter. It can be any letter in the Latin, Greek or Cyrillic alphabet. Each region in the Venn diagram is subset of \\( X \\): for example, the upper left circle contains all the letters in the Greek alphabet. But each region can also be seen as a proposition: a statement about the world. For example, the upper left circle corresponds to the proposition "The letter belongs to the Greek alphabet".

As a result, everything you can do with subsets of \\( X \\) turns into something you can do with propositions. Suppose \\( P, Q, \\) and \\( R \\) are subsets of \\( X \\). We can also think of these as propositions, and:

* if \\( P \subseteq Q \\) we say the proposition \\( P \\) **implies** the proposition \\( Q \\), and we write \\( P \implies Q \\).

* If \\( P \cap Q = R \\) we say \\(P \textbf { and } Q = R \\).

* If \\( P \cup Q = R \\) we say the proposition \\( P \textbf{ o r} Q = R \\).

All the rules obeyed by "subset", "and" and "or" become rules obeyed by "implies", "and" and "or".

I hope you know this already, but if you don't, you're in luck: _this is this most important thing you've heard all year!_ Please think about it and ask questions until it revolutionizes the way you think about logic.

But really, all this stuff is about one particular way of getting a poset from the set \\( X \\).

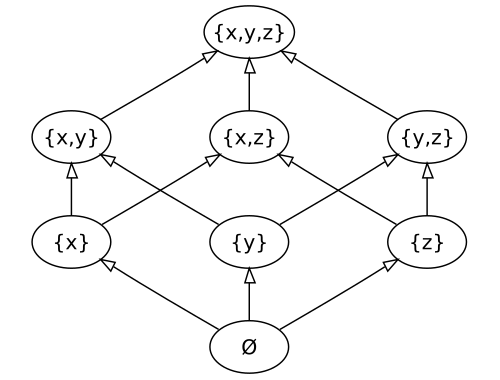

For any set \\( X \\) the **[power set](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_set)** of \\( X \\) is the collection of all subsets of \\( X \\). We call it \\( P(X) \\). It's a poset, where the partial ordering is \\( \subseteq \\).

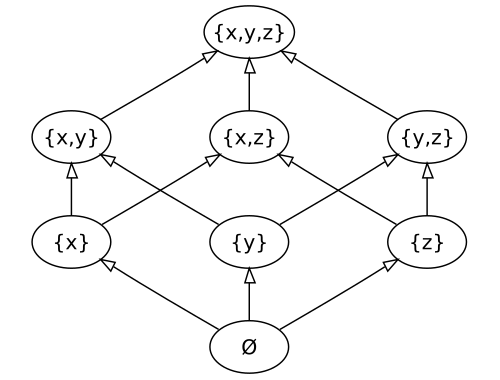

For example, here is a picture of the poset \\( P(X) \\) when \\( X = \\{x,y,z\\} \\):

This is a picture of some set \\( X \\) of "states of the world". But the world here is very tiny: it's just a letter. It can be any letter in the Latin, Greek or Cyrillic alphabet. Each region in the Venn diagram is subset of \\( X \\): for example, the upper left circle contains all the letters in the Greek alphabet. But each region can also be seen as a proposition: a statement about the world. For example, the upper left circle corresponds to the proposition "The letter belongs to the Greek alphabet".

As a result, everything you can do with subsets of \\( X \\) turns into something you can do with propositions. Suppose \\( P, Q, \\) and \\( R \\) are subsets of \\( X \\). We can also think of these as propositions, and:

* if \\( P \subseteq Q \\) we say the proposition \\( P \\) **implies** the proposition \\( Q \\), and we write \\( P \implies Q \\).

* If \\( P \cap Q = R \\) we say \\(P \textbf { and } Q = R \\).

* If \\( P \cup Q = R \\) we say the proposition \\( P \textbf{ o r} Q = R \\).

All the rules obeyed by "subset", "and" and "or" become rules obeyed by "implies", "and" and "or".

I hope you know this already, but if you don't, you're in luck: _this is this most important thing you've heard all year!_ Please think about it and ask questions until it revolutionizes the way you think about logic.

But really, all this stuff is about one particular way of getting a poset from the set \\( X \\).

For any set \\( X \\) the **[power set](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Power_set)** of \\( X \\) is the collection of all subsets of \\( X \\). We call it \\( P(X) \\). It's a poset, where the partial ordering is \\( \subseteq \\).

For example, here is a picture of the poset \\( P(X) \\) when \\( X = \\{x,y,z\\} \\):

As you can see, it looks like a 3-dimensional cube. Here's a picture of \\( P(X) \\) when \\( X \\) has 4 elements:

As you can see, it looks like a 3-dimensional cube. Here's a picture of \\( P(X) \\) when \\( X \\) has 4 elements:

In this picture we say whether each element is in or out of the subset by writing a 1 or 0. This time we get a 4-dimensional cube.

What's the union of two subsets \\( S, T \subseteq X \\)? It's the smallest subset of \\( X \\) that contains both \\( S \\) and \\( T \\) as subsets. This is an example of a concept we can define in any poset:

**Definition.** Given a poset \\( (A, \le) \\), the **join** of \\( a, b \in A \\), if it exists, is the least element \\( c \in A \\) such that \\( a \le c \\) and \\( b \le c \\). We denote the join of \\( a \\) and \\( b \\) as \\( a \vee b \\).

Quite generally we can try to think of _any_ poset as a poset of propositions. Then \\( \vee \\) means "or". In the logic we're studying today, this poset is \\( P X \\) and \\( \vee \\) is just "union", or \\( \cup \\).

Similarly, what's the intersection of two subsets \\( S, T \subseteq X \\)? Well, it's the largest subset of \\( X \\) that is contained as a subset of both \\( S \\) and \\( T \\). Again this is an example of a concept we can define in any poset:

**Definition.** Given a poset \\( (A, \le) \\), the **meet** of \\( a, b \in A \\), if it exists, is the greatest element \\( c \in A \\) such that \\( c \le a \\) and \\( c \le b \\). We denote the meet of \\( a \\) and \\( b \\) as \\( a \wedge b \\).

When we think of a poset as a poset of propositions, \\( \wedge \\) means "and". When our poset is \\( P(X) \\), \\( \wedge \\) is just "intersection". \\( \cap \\).

We could go on with this, and if this were a course on classical logic I would. But this is a course on applied category theory! So, we shouldn't just stick with a fixed set \\( X \\). We should see what happens when we let it vary! We get a poset of propositions for each set \\( X \\), but all these posets are related to each other.

I'll talk about this more next time, but let me give you a teaser now. Say we have two sets \\( X \\) and \\( Y \\) and a function \\( f : X \to Y \\). Then we get a monotone map from the poset \\( P(Y) \\) to the poset \\( P(X) \\), called

\[ f^* : P(Y) \to P(X) \]

For any \\( S \in P(Y) \\), the set \\( f^*(S) \in P(X) \\) is defined like this:

\[ f^*(S) = \\{ x \in X : \; f(x) \in S \\} \]

Next time, I'll show you this monotone map has both a left and a right adjoint! And these turn out to be connected to the logical concepts of "there exists" and "for all". I believe this was first discovered by the great category theorist [Bill Lawvere](https://www.emis.de/journals/TAC/reprints/articles/16/tr16abs.html).

So you see, I haven't given up talking about left and right adjoints. I'm really just getting ready to explain how they show up in logic: first in good old classical "subset logic", and then in the weird new "partition logic".

**[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**

In this picture we say whether each element is in or out of the subset by writing a 1 or 0. This time we get a 4-dimensional cube.

What's the union of two subsets \\( S, T \subseteq X \\)? It's the smallest subset of \\( X \\) that contains both \\( S \\) and \\( T \\) as subsets. This is an example of a concept we can define in any poset:

**Definition.** Given a poset \\( (A, \le) \\), the **join** of \\( a, b \in A \\), if it exists, is the least element \\( c \in A \\) such that \\( a \le c \\) and \\( b \le c \\). We denote the join of \\( a \\) and \\( b \\) as \\( a \vee b \\).

Quite generally we can try to think of _any_ poset as a poset of propositions. Then \\( \vee \\) means "or". In the logic we're studying today, this poset is \\( P X \\) and \\( \vee \\) is just "union", or \\( \cup \\).

Similarly, what's the intersection of two subsets \\( S, T \subseteq X \\)? Well, it's the largest subset of \\( X \\) that is contained as a subset of both \\( S \\) and \\( T \\). Again this is an example of a concept we can define in any poset:

**Definition.** Given a poset \\( (A, \le) \\), the **meet** of \\( a, b \in A \\), if it exists, is the greatest element \\( c \in A \\) such that \\( c \le a \\) and \\( c \le b \\). We denote the meet of \\( a \\) and \\( b \\) as \\( a \wedge b \\).

When we think of a poset as a poset of propositions, \\( \wedge \\) means "and". When our poset is \\( P(X) \\), \\( \wedge \\) is just "intersection". \\( \cap \\).

We could go on with this, and if this were a course on classical logic I would. But this is a course on applied category theory! So, we shouldn't just stick with a fixed set \\( X \\). We should see what happens when we let it vary! We get a poset of propositions for each set \\( X \\), but all these posets are related to each other.

I'll talk about this more next time, but let me give you a teaser now. Say we have two sets \\( X \\) and \\( Y \\) and a function \\( f : X \to Y \\). Then we get a monotone map from the poset \\( P(Y) \\) to the poset \\( P(X) \\), called

\[ f^* : P(Y) \to P(X) \]

For any \\( S \in P(Y) \\), the set \\( f^*(S) \in P(X) \\) is defined like this:

\[ f^*(S) = \\{ x \in X : \; f(x) \in S \\} \]

Next time, I'll show you this monotone map has both a left and a right adjoint! And these turn out to be connected to the logical concepts of "there exists" and "for all". I believe this was first discovered by the great category theorist [Bill Lawvere](https://www.emis.de/journals/TAC/reprints/articles/16/tr16abs.html).

So you see, I haven't given up talking about left and right adjoints. I'm really just getting ready to explain how they show up in logic: first in good old classical "subset logic", and then in the weird new "partition logic".

**[To read other lectures go here.](http://www.azimuthproject.org/azimuth/show/Applied+Category+Theory#Course)**