What's the pattern in this sequence?

In 2 dimensions, the most symmetrical polygons of all are the 'regular polygons'. All the edges of a regular polygon are the same length, and all the angles are equal. If you only count the convex ones, it's easy to list all the regular polygons: the equilateral triangle, the square, the regular pentagon, and so on. In short, there is an infinity of regular polygons: one with n sides for each n > 3. (The cases n = 0,1, and 2 are bit degenerate.)

In 3 dimensions, the most symmetrical polyhedra of all are the 'regular polyhedra', also known as the 'Platonic solids'. All the faces of a Platonic solid are regular polygons of the same size, and all the vertices look identical. We also demands that our Platonic solids be convex. There are only five Platonic solids:

The story goes on... but in higher dimensions one usually uses the term 'regular polytopes' instead of 'Platonic solids'. All the faces of a regular polytope must be lower-dimensional regular polytopes of the same size and shape, and all the vertices, edges, etc. have to look identical. Maximal symmetry, that's the name of the game! (Also, I'll only be talking about convex polytopes.)

In 4 dimensions, there are exactly six regular polytopes.

How can visualize these? Well, a Platonic solid looks a lot like a sphere in ordinary 3-dimensional space, with its surface chopped up into polygons. So, a 4d regular polytope looks a lot like a sphere in 4-dimensional space with its surface chopped up into polyhedra! A sphere in 4-dimensional space is called a '3-sphere', since people living on its surface would experience it as a 3-dimensional universe with the curious feature that if you hop aboard a rocket and shoot off straight in any direction, you eventually wind up back where you started. (This is just like what happens when you start walking in a straight line in any direction on an ordinary sphere.)

So, we can visualize the regular polytopes in 4 dimensions by taking a 3-sphere and drawing it chopped up into polyhedra. A 3-sphere is hard to draw until you realize it looks just like ordinary 3d space except that it 'wraps around'... very far away from here. But if we ignore that, and just draw a nearby portion of the 3-sphere chopped up into polyhedra, with everything outside this portion being one big polyhedron, we'll do okay. And this is what we get:

Some people call this a '5-cell', 'pentatope' or 'pentachoron'.

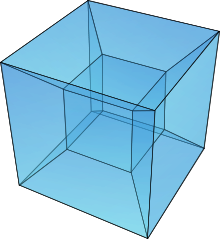

You'll notice the edges are bulging out on these pictures: that's because they're drawn in a 3-sphere! We can also draw the pictures in a 'flat' style, which may be more familiar, especially for the hypercube:

This shows the 'walls' of the 8 cubical faces, as well as their edges. Do you see the 8 cubical faces? You may only see 7, but that's because you're ignoring the cube on the outside of the whole picture.... remember, we're in a 3-sphere here.

Some people call this an 'orthoplex', or a 'hexadecachoron'.

Zounds!

You might things would keep getting more complicated in higher dimensions. But it doesn't! 4-dimensional space is the peak of complexity as far as regular polytopes go. From then on, it gets pretty boring. This is one of many examples of how 4-dimensional geometry and topology are more complicated, in certain ways, than geometry and topology in higher dimensions. And the spacetime we live in just happens to be 4-dimensional. Hmm.

In 5 or more dimensions, there are only three regular polytopes:

How can we understand the proliferation of regular polytopes in 4 dimensions? And how can we visualize them?

For starters, try Tony Smith's webpage. If you cross your eyes while gazing at this stereoscopic pair of images, you will see a 24-cell rotating in the 4th dimension, with the 4th dimension depicted using color. If you gaze long enough, you may become enlightened.

Here's another way to visualize the 4-dimensional regular polytopes.

Ever make a cube out of paper? You draw six squares on the paper in a

cross-shaped pattern, cut the whole thing out, and then fold it

up... it's called a 'foldout model' of a cube.

When you do this, you're taking advantage of the fact that the interior

angles of 3 squares don't quite add up to 360 degrees: they only add up

to 270 degrees. So if you try to tile the plane with squares in such a

way that only 3 meet at each vertex, the pattern naturally 'curls up'

into the 3rd dimension - and becomes a cube!

The same idea applies to all the other Platonic solids. And

we can understand the 4d regular polytopes in the same way!

For example: suppose you take a cube and push in the middle of each

face, making a dent shaped like an inverted pyramid. Keep pushing

in until the tips of all these pyramids meet at the cube's center.

Now you have a cube with 6 pyramid-shaped dents that meet at a point in

the center. Isn't it tempting to take 6 regular octahedra and fit their

corners into these dents? If they fit perfectly, maybe we could tile

3-dimensional space with regular octahedra, 6 meeting at each vertex!

Alas, they don't fit perfectly: there's a little 'wiggle room'.

You can either take my word for this, or check it yourself....

But we can snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. We can't tile

3d space with octahedra this way, but if we let the pattern 'curl

up' into the 4th dimension, we get a 4d regular polytope! This is

the 24-cell. It has 24 octahedral faces, 6 meeting at each vertex.

Next let's do the same trick starting with a regular tetrahedron.

Push in each triangular face, getting a dent in the shape of

somewhat squat triangular pyramid. Keep pushing until the tips of

all these dents meet at the center of our original tetrahedron.

Now stick a regular tetrahedron in each dent. There's a lot of wiggle

room this time. So let the pattern curl up into the 4th

dimension... and get the 4-simplex, with 5 tetrahedral faces, 4

meeting at each vertex!

In fact, there's so much room in these dents that we can even stick

the corner of a cube in each one. If we do this, there's

still some wiggle room - and if we let the pattern curl up into the

4th dimension, we get the hypercube, with 8 cubical faces, 4 meeting

at each vertex!

Actually, we can even go further - we can stick the corner of a

dodecahedron in each dent. This time there's only a tiny bit

of wiggle room. If we let the pattern curl up, we get the 120-cell,

with 120 dodecahedral faces, 4 meeting at each vertex!

This is fun - so let's try another Platonic solid. This time, let's

start with a regular octahedron. Push in each of the 8 triangular

faces, getting dents in the shape of triangular pyramids. Keep

pushing until the dents meet at the middle, and then stick a regular

tetrahedron in each of the 8 dents! There's some wiggle room - though

not as much as last time - so again, let the pattern curl up in

4-dimensional space... and get the 4-dimensional cross-polytope, with

16 tetrahedral faces, 8 meeting at each vertex!

Next, let's take an icosahedron and do the same trick. Push in each

of the 20 triangular faces, making dents in the shape of triangular

prisms, and keep pushing until the tips of all these dents meet at the

center of the icosahedron. Now stick a regular tetrahedron in each

dent. There's only a tiny bit of wiggle room this time! But go ahead,

let the pattern curl up into the 4th dimension.... and get the

hypericosahedron, with 600 tetrahedral faces, 20 meeting at each vertex!

(Note the pattern: the less wiggle room we have, the bigger our

4d regular polytope is.)

Finally, let's do the same procedure starting from a dodecahedron.

Here each dent looks like it wants the corner of an icosahedron

put into it - so go ahead and try!

Hmm. Wait a minute! Is there wiggle room this time, or not?

And even if there is, are we guaranteed to get a regular polytope

using this trick?

I'll leave this as a little puzzle for you... If you give up,

click here.

I hope you've done your best to visualize everything I just said. But

if you had trouble, don't feel too bad! Andrew Weimholt has drawn

pictures of foldout

models of the 4d regular polytopes. If you look at these, what I

said should make more sense.

While you're pondering that, let me tell you another way to

get some of the 4d regular polytopes. This method involves quaternions,

which are a souped-up version of the complex numbers with three

square roots of -1, called i, j, and k. A typical quaternion

looks like this:

where a,b,c, and d are real numbers. To multiply the quaternions, you

need to use these rules, invented by Hamilton back in 1843:

Let's start with the 24-cell, since this guy has no analog in

other dimensions.

Since the vertices of the 24-cell lie on the unit sphere in

4 dimensions, we can think of

its vertices as certain unit quaternions. The 24-cell

happens to have, not only 24 faces, but also 24 vertices!

We can take

them to be precisely the unit 'Hurwitz integral quaternions',

which are quaternions of the form

where a,b,c,d are either all integers or all integers plus 1/2.

One can check that the Hurwitz integral quaternions are closed

under multiplication, so the vertices of the 24-cell form a

subgroup of the unit quaternions. A regular polytope that's

a symmetry group in its own right - ponder that while you

cross your eyes and gaze at it spinning around!

Similarly, the 600-cell has 120 vertices, which we can think

of as certain unit quaternions. We can take them to be precisely the unit

'icosians'. These are quaternions of the form

where a,b,c,d all live in the 'golden field' - meaning

that they're of the form x + √5 y where x and y are

rational. Since the icosians are closed under multiplication

a group under multiplication, the vertices of the 120-cell

also form a group!

The vertices of the 4-dimensional cross-polytope also form

a subgroup of the unit quaternions. But this one is a little

less exciting. We just take the quaternions of the form

where one of the numbers a,b,c,d is 1 or -1, and the rest

are zero. This 8-element subgroup is sometimes

called 'the quaternion group'.

Those are all the 4-dimensional regular polytopes that are

also groups. Three out of six ain't bad!

But we can get most of the rest using duality.

In general, the 'dual' of a regular polytope is another

polytope, also regular, having one vertex in the center of

each face of the polytope we started with. The dual of the

dual of a regular polytope

is the one we started with (only smaller). So polytopes

come in mated pairs - except for some 'self-dual' ones.

In 2 dimensions, every regular polytope is its own dual.

In 3 dimensions, the tetrahedron is self-dual. The dual

of the cube is the octahedron. And the dual of the dodecahedron

is the icosahedron.

In 4 dimensions, the 4-simplex is self-dual. The 24-cell is

also self-dual - that's why it had 24 faces and also 24 vertices!

The dual of the hypercube is the 4-dimensional cross-polytope. The

dual of the 120-cell is the 600-cell.

In higher dimensions, the n-simplex is self-dual, and

the dual of the n-cube is the n-dimensional

cross-polytope.

But what is so special about 4 dimensions, exactly?

Well, there are very few dimensions in which the unit sphere

is also a group. It happens only in dimensions 1, 2, and 4!

In 1 dimensions the unit sphere is just two points, which we

can think of as the unit real numbers, -1 and 1. In 2 dimensions

we can think of the unit sphere as the unit complex numbers,

exp(iθ). In 4 dimensions we can think of the unit sphere

as the unit quaternions.

Only in these dimensions do we get polytopes that are also groups in a

natural way. In 2 dimensions all the regular n-gons correspond to

groups consisting of the unit complex numbers exp(2πi/n). In 4

dimensions things are more subtle and interesting. It's especially

interesting because the group of unit quaternions, also known as

SU(2), happens to be the 'double cover' of the rotation group in 3

dimensions. Roughly speaking, this means that there is a nice

function sending 2 elements of SU(2) to each rotation in 3 dimensions.

This gives a slick way to construct the 600-cell, or hypericosahedron.

Take the icosahedron in 3 dimensions. Consider its group of

rotational symmetries. This is a 60-element subgroup of the rotation

group in 3 dimensions. Now look at the corresponding subgroup of

SU(2) - its 'double cover', so to speak. This is a 120-element

subgroup of the unit quaternions. These are the vertices of the

hypericosahedron! So in a very real sense, the hypericosahedron

is just the symmetries of the icosahedron! This trick doesn't

work in higher dimensions. This is one thing that's very cool about 4

dimensions - it inherits the hypericosahedron and the

hyperdodecahedron from the the fact that the icosahedron and

dodecahedron happen to exist in 3 dimensions.

Similarly, the 24-cell comes from the symmetries of the tetrahedron!

I copied the pictures of rotating Platonic solids from the Wikipedia

article on Platonic solids

under the terms of the GNU

Free Documentation License: these were made by Cyp. I also copied

the pictures of 4d regular polytopes from the Wikipedia articles on

these polytopes, under the terms of the relevant copyrights: these

were made by Tom Run using Robert Webb's Stella software. These

articles are a great place to get started on understanding the

Platonic solids.

For more information try Eric Weisstein's Mathworld

website. He has lots of information on Platonic solids

and 4d

geometry. You can rotate the Platonic solids and 4d polytopes

using your mouse!

If you have access to VRML, you can also have fun with George Hart's

Encyclopedia

of Polyhedra, which has over 1000 polyhedra in it. (VRML stands for

"virtual reality modelling language", and it's available as a plugin

for most browsers.)

If you want to learn a lot about regular polytopes,

read this book by the king of geometry:

For more about the icosahedron, see "Some

thoughts on the number six".

For more about icosians and related marvels, see

week20 of This Week's Finds.

For more about the Platonic solids, how fool's gold fooled the

Greeks into inventing the regular dodecahedron, and highly

symmetric structures in higher dimensions,

see week62,

week63,

week64, and

week65 of my weekly column on mathematical

physics. This story continues at a deeper level in

week186 and

week187.

For more on the Hurwitz integral quaternions and the mysteries

of triality in 8 dimensions, see week91.

For a deeper look at relations between different Platonic solids,

and also more stuff about the 24-cell and 600-cell, see

week155.

Everything sufficiently beautiful is connected to all other

beautiful things! Follow the beauty and you will learn all

the coolest stuff. The Platonic solids are a nice

place to start.

© 2020 John BaezFoldout Models of 4-Dimensional Platonic Solids

Platonic Solids and the Quaternions

ij = -ji = k

jk = -kj = i

ki = -ik = j

Directions for Further Study

For more on the dodecahedron, see "Tales of

the dodecahedron: from Pythagoras through Plato to Poincaré".

From Kepler's Mysterium

Cosmographicium,

in which he modeled the orbits of the

five known planets using Platonic solids.

The cube fits outside

all those shown above.

Of the infinite forms we must select the most

beautiful, if we are to proceed in due order.... — Plato, in the

Timaeus

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu

home