An important early tuning system is Pythagorean tuning, where we force all frequency ratios to involve only powers of 2 and 3. In music, 3/2 is the 'fifth’: the most consonant of intervals except for the octave.

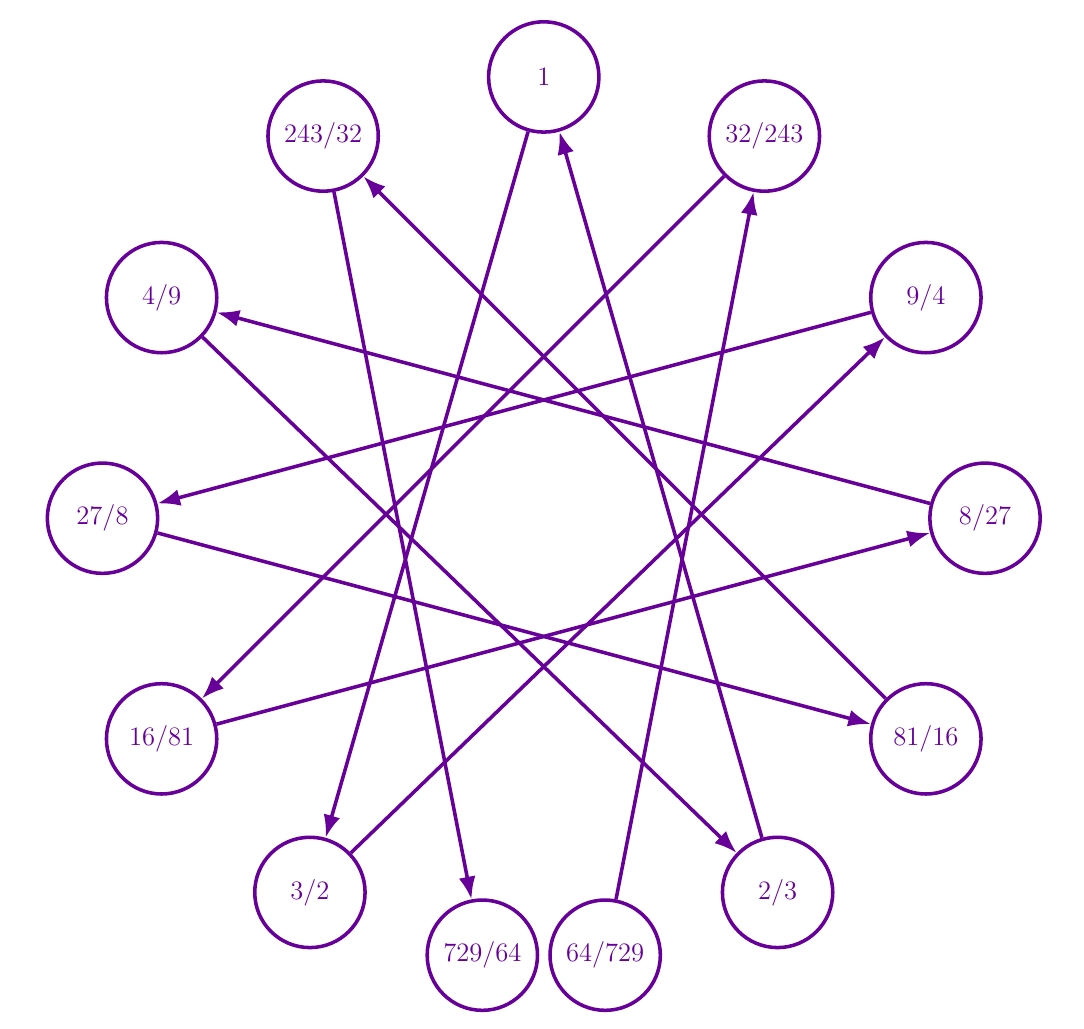

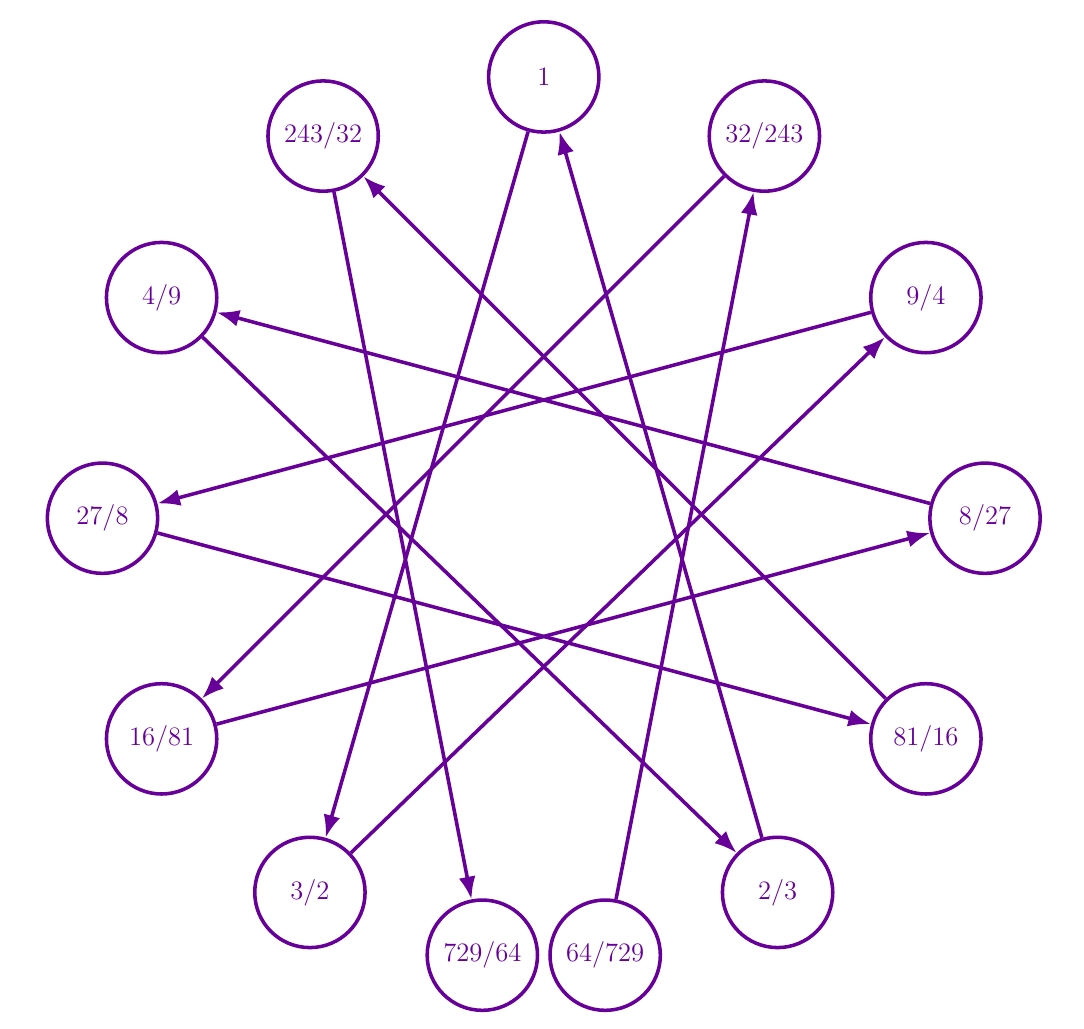

If we start with some frequency and go up and down by powers of 3/2, we create the 'circle of fifths’ shown above. It's almost a 12-pointed star, with one point for each note in the 12-tone equal-tempered scale.

Almost — but not quite! When we go up 12 fifths, we get a tone that's almost but not quite 2 times the frequency we started with. In other words, it's almost but not quite 7 octaves higher. So there's a glitch.

Here I've stuck that glitch at the opposite from the pitch labeled 1. That's a good place for it, because the spot directly opposite 1 is called the 'tritone’, or sometimes diabolus in musica: the 'devil in music’.

Let me explain the chart a bit more carefully. I started with any pitch and arbitrarily called its frequency 1. Then I climbed up 6 fifths, multiplying the frequency by 3/2 each time, getting pitches with frequencies

$$ 1, 3/2, 9/4, 27/8, 81/16, 243/32, 729/64 $$

Going all the way around the circle clockwise means going up an octave: that is, multiplying the frequency by 2. So each time I multiplied the frequency by 3/2, I went log2(3/2) of the way clockwise around the circle: that is, about 0.585 of the way around, a bit more than half-way.

Then I climbed down 6 fifths, going counterclockwise and dividing the frequency by 3/2 each time, getting pitches with frequencies

$$ 1, 2/3, 4/9, 8/27, 16/81, 32/243, 64/729 $$

These are the reciprocals of the numbers we saw going up.

Why did I stop when I did? 729/64 is nowhere close to 64/729, but their ratio is almost a power of 2:

$$ \displaystyle{ \frac{729/64}{64/729} = \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^{12} \! \approx 129.7 } $$

while

$$ \displaystyle{ 2^7 = 128 } $$

So our star is close to a 12-pointed star. But there's a glitch. And the size of the glitch is called the Pythagorean comma:

$$ \displaystyle{ \frac{(3/2)^{12}}{2^7} = \frac{3^{12}}{2^{19}} \approx 1.01364326477 } $$

This is one of the problems afflicting Pythagorean tuning, and later I'll say a bit about how people deal with it.

Now let's multiply the frequencies we've seen by powers of 2 to make them lie between 1 and 2. That gives us a scale that lies within a single octave:

These different pitches have names, by the way! Not just in Pythagorean tuning but in other related tuning systems, like the equal-tempered scale widely used in music today. Here they are: with their frequencies in the Pythagorean system: $$ \def\arraystretch{1.4} \begin{array}{lc} \textbf{tonic} & 1 \\ \textbf{minor 2nd} & \frac{256}{243} \\ \textbf{major 2nd} & \frac{9}{8} \\ \textbf{minor 3rd} & \frac{32}{27} \\ \textbf{major 3rd} & \frac{81}{64} \\ \textbf{major 4th} & \frac{4}{3} \\ \textbf{diminished 5th} & \frac{1024}{729} \\ \textbf{augmented 4th} & \frac{729}{512} \\ \textbf{perfect 5th} & \frac{3}{2} \\ \textbf{minor 6th} & \frac{128}{81} \\ \textbf{major 6th} & \frac{27}{16} \\ \textbf{minor 7th} & \frac{16}{9} \\ \textbf{major 7th} & \frac{243}{128} \\ \textbf{octave} & 2 \\ \end{array} $$

In the equal-tempered scale there's no difference between the augmented 4th and the diminished 5th: they're both the tritone. But in Pythagorean tuning they're different. And surprisingly, the augmented 4th is higher in pitch than the diminished 5th.

It may or may not help you to see the abbreviations for these different pitch names:

I could talk about this chart all day, but most of what I'd say would apply just as well to the equal-tempered scale. The big difference is that in Pythagorean tuning, unlike the equal-tempered scale, the augmented 4th (A4) and diminished fifth (d5) are not the same note. They are very close: the chart is not to scale, and if it were these two pitches would be almost on top of each other. But they're not the same!

It also may or may not help you to see the names for these pitches when the frequency we arbitrarily called 1 is the note called C:

We get a funny version of the scale with 13 notes, because F sharp (the augmented 4th in the key of C) is different from G flat (the diminished 5th).

Okay, but what if we want a scale with just 12 notes? We usually remove the diminished 5th, and make the augmented 4th do whatever jobs the diminished 5th would have done! So, we change our chart to this:

Or, in terms of frequencies, this:

This looks terrible, but more importantly it creates a badly out-of-tune pair of notes, namely those connected by the new red edge. These pitches have an ugly frequency ratio of

$$ \displaystyle{ \frac{729/512}{256/243} = \frac{3^{11}}{2^{17}} \approx 1.351524} $$

If we hadn't used the augmented 4th for a job the diminished 5th should be doing, we'd have gotten the much nicer-sounding ratio

$$\displaystyle{ \frac{1024/729}{256/243} = \frac{4}{3} \approx 1.333333} $$

The difference is audible and unpleasant: we've created what's called a 'wolf interval’, called that because it howls like a wolf. Unsurprisingly, the ugly ratio divided by the nicer ratio is our old nemesis, the Pythagorean comma:

$$\displaystyle{ \frac{3^{11}/2^{17}}{4/3} = \frac{3^{12}}{2^{19}} \approx 1.01364326477 } $$

It's interesting to look at the frequency ratios of neighboring notes in the Pythagorean scale: $$ \def\arraystretch{1.4} \begin{array}{lcccc} \textbf{minor 2nd / tonic} \phantom{ABC} & \frac{256}{243}\big/1 &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 2nd / minor 2nd} & \frac{9}{8}\big/\frac{256}{243} &=& 2187/2048 \\ \textbf{minor 3rd / major 2nd} & \frac{32}{27}\big/\frac{9}{8} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 3rd / minor 3rd} & \frac{81}{64}\big/\frac{32}{27} &=& 2187/2048\\ \textbf{major 4th /major 3rd} & \frac{4}{3}\big/\frac{81}{64} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{augmented 4th / major 4th} & \frac{729}{512}\big/\frac{4}{3} &=& 2187/2048 \\ \textbf{perfect 5th / augmented 4th} & \frac{3}{2}\big/\frac{729}{512} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{minor 6th / perfect 5th} & \frac{128}{81}\big/\frac{3}{2} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 6th / minor 6th} & \frac{27}{16}\big/\frac{128}{81} &=& 2187/2048 \\ \textbf{minor 7th / major 6th} & \frac{16}{9}\big/\frac{27}{16} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 7th / minor 7th} & \frac{243}{128}\big/\frac{16}{9} &=& 2187/2043 \\ \textbf{octave / major 7th} & 2\big/\frac{243}{128} &=& 256/243 \\ \end{array} $$

In the equal-tempered scale the frequency ratio of neighboring notes is always 21/12, and it's called a semitone. But as you can see, in the Pythagorean scale some neighboring notes have a frequency ratio of 256/243, while others have a ratio of 2187/2048. So there are two kinds of semitones in the Pythagorean scale:

The Pythagorean chromatic semitone is bigger than the Pythagorean diatonic semitone. How much bigger? What's their ratio?

$$\displaystyle{ \frac{2187/2048}{256/243} = \frac{3^{12}}{2^{19}} \approx 1.01364326477 } $$

Yes, it's the Pythagorean comma! Like a bad penny, it keeps coming back to haunt us.

By the way, the word 'limma' is from a Greek word meaning 'remnant', and it's used for several small intervals in music. The word 'apotome' is from a Greek word meaning 'cutting off', and it's apparently used only for this particular interval, as well as other things in mathematics and optics.

The somewhat irregular pattern of semitones in my chart above would become symmetrical if we had kept the diminished 5th, but then there would be a Pythagorean comma between the augmented 4th and diminished 5th, like this: $$ \def\arraystretch{1.4} \begin{array}{lcccc} \textbf{minor 2nd / tonic} \phantom{ABC} & \frac{256}{243}\big/1 &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 2nd / minor 2nd} & \frac{9}{8}\big/\frac{256}{243} &=& 2187/2048 \\ \textbf{minor 3rd / major 2nd} & \frac{32}{27}\big/\frac{9}{8} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 3rd / minor 3rd} & \frac{81}{64}\big/\frac{32}{27} &=& 2187/2048\\ \textbf{major 4th / major 3rd} & \frac{4}{3}\big/\frac{81}{64} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{diminished 5th / major 4th} & \frac{1024}{729}\big/\frac{4}{3} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{augmented 4th / diminished 5th} & \frac{729}{512}\big/\frac{1024}{729} &=& 531441/524288 \\ \textbf{perfect 5th / augmented 4th} & \frac{3}{2}\big/\frac{729}{512} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{minor 6th / perfect 5th} & \frac{128}{81}\big/\frac{3}{2} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 6th / minor 6th} & \frac{27}{16}\big/\frac{128}{81} &=& 2187/2048 \\ \textbf{minor 7th / major 6th} & \frac{16}{9}\big/\frac{27}{16} &=& 256/243 \\ \textbf{major 7th/minor 7th} & \frac{243}{128}\big/\frac{16}{9} &=& 2187/2043 \\ \textbf{octave / major 7th} & 2\big/\frac{243}{128} &=& 256/243 \\ \end{array} $$

Now the chart is symmetrical from top to bottom. The big nasty fraction in the middle is the Pythagorean comma:

$$\displaystyle{ \frac{531441}{524288} = \frac{3^{12}}{2^{19}} \approx 1.01364326477 }$$

Besides the Pythagorean comma — and the wolf interval we get if we try to avoid it — another big problem with Pythagorean tuning is that some very important intervals are represented by fairly complicated fractions. The ear seems to enjoy simple fractions! There are other tuning systems that do better at this, like 'just intonation’. For example, in Pythagorean tuning the minor third is 32/27 above the tonic, while in just intonation it's 6/5. In Pythagorean tuning the major third is a ridiculous 81/64 above the tonic, while in just intonation it's 5/4. Arguably just intonation gets these things right, while Pythagorean tuning gets them wrong.

To finish off, here's a comparison between Pythagorean tuning and equal temperament: \[ \def\arraystretch{1.4} \begin{array}{lrrrc} & \textbf{ Pythagorean} & & \textbf{equal-tempered} & \textbf{Pythagorean/equal-tempered} \\ \textbf{tonic} & 1 = 1.000000 & = & 2^{0/12} = 1.000000 & 1 \\ \textbf{minor 2nd} & \frac{256}{243} \approx 1.053498 & {\color{blue}{<}} & 2^{1/12} \approx 1.059463 & \color{blue} 1 - 0.005630 \\ \textbf{major 2nd} & \frac{9}{8} = 1.125000 & {\color{red}{>}} & 2^{2/12} \approx 1.122462 & \color{red} 1 + 0.002261 \\ \textbf{minor 3rd} & \frac{32}{27} \approx 1.185185 & {\color{blue}{<}} & 2^{3/12} \approx 1.189207 & \color{blue} 1 - 0.003382 \\ \textbf{major 3rd} & \frac{81}{64} = 1.265625 & {\color{red}{>}} & 2^{4/12} \approx 1.259921 & \color{red} 1 + 0.004527\\ \textbf{perfect 4th} & \frac{4}{3} \approx 1.333333 & {\color{blue}{<}} & 2^{5/12} \approx 1.334840 & \color{blue} 1 - 0.001129 \\ \textbf{diminished 5th} & \frac{1024}{729} \approx 1.404664 & {\color{blue}{<}} & 2^{6/12} \approx 1.414214 & \color{blue} 1 - 0.006753 \\ \textbf{augmented 4th} & \frac{729}{512} \approx 1.423828 & {\color{red}{>}} & 2^{6/12} \approx 1.414214 & \color{red} 1 + 0.006799 \\ \textbf{perfect 5th} & \frac{3}{2} = 1.500000 & {\color{red}{>}} & 2^{7/12} \approx 1.498307 & \color{red}1+ 0.001130 \\ \textbf{minor 6th} & \frac{128}{81} \approx 1.580247 & {\color{blue}{<}} & 2^{8/12} \approx 1.587401 & \color{blue} 1 - 0.004507 \\ \textbf{major 6th} & \frac{27}{16} = 1.687500 & {\color{red}{>}} & 2^{9/12} \approx 1.681793 & \color{red} 1 + 0.003394 \\ \textbf{minor 7th} & \frac{16}{9} \approx 1.777778 & {\color{blue}{<}} & 2^{10/12} \approx 1.781797 & \color{blue} 1- 0.002256 \\ \textbf{major 7th} & \frac{243}{128} \approx 1.898438 & {\color{red}{>}} & 2^{11/12} \approx 1.887749 & \color{red} 1 + 0.005662 \\ \textbf{octave} & 2 = 2.000000 & = & 2^{12/12} = 2.000000 & 1\\ \end{array} \]

I'm not trying to imply that equal temperament is 'correct', but at right I'm showing the Pythagorean frequency divided by the corresponding equal-tempered frequency. It's a bit remarkable how close they are! The biggest deviations occur for the augmented 4th and diminished 5th, which are the same in equal temperament but separated by a comma in the Pythagorean scale. The second biggest deviations occur for the minor 2nd and major 7th. All these are fairly dissonant intervals even in the best of worlds. But the third biggest occur for the major 3rd and minor 6th.

Here's a picture comparing Pythagorean tuning and equal temperament:

Equal-tempered is black and Pythagorean is green. You can see the diminished fifth and augmented fourth straddling the tritone.

So much more to say! But I'll quit here for now.

Equal Temperament (Part 1)

I've explained how Pythagorean tuning, one of the older tuning systems, arises from the fact that twelve fifths is almost the same as seven octaves. In other words, multiplying by 3/2 twelve times is almost the same as multiplying by 2 seven times: \[ \displaystyle{ \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^{12} \! \approx 129.7 > 128 = 2^7 } \]

But not quite! That's why the star above does not quite close.

In the most widely used modern scale, we deal with this discrepancy by using a fifth that does not have a frequency ratio of 3/2, but rather

\[ \displaystyle{ 2^{7/12} \approx 1.49830707688} \]

It's a bit off, but not much. So it sounds pretty good, and most of us have decided to accept it (though I love those of you who haven't). We then equally divide this fifth into 7 steps, each with a frequency ratio of 21/12. We thus divide the octave into 12 steps, each with a frequency ratio of 21/12. The result is called the equal-tempered 12-tone scale, or 12-TET for short.

The only question I want to discuss today is: why 12 tones? What if we tried an equal-tempered scale with some other number of tones?

The historical question of how Western music arrived at a 12-tone scale is complicated. It seems much of the evidence is lost in the mists of time. I'm not qualified to tackle this question. Indeed, nothing I've read so far has convinced me that anyone is qualified, though I want to read more. So instead I'll just talk about the math.

Furthermore, I'll take a very narrow view of the question! When choosing a tuning system there are many factors at work. At the very least, for each interval you might like to play, you should ask how well a given tuning system accommodates that interval. In common practice Western music this includes asking how all the major thirds and fifths sound in a given tuning system — since major triads, consisting of a tone, the major third above that tone, and the perfect fifth above that tone, are so fundamental to this music. It's generally thought that a really nice major triad has frequency ratios

\[ 1 : \frac{5}{4} : \frac{3}{2} \]

And so, mathematically, we can take any tuning system and ask how closely its major triads come to having these frequency ratios. For example, in just intonation we make some major triads have exactly these frequency ratios... while others are quite bad.

But because I've recently been thinking about Pythagorean tuning, which is about fifths, in this entry I won't talk about major thirds at all — much less the myriads of other issues — and focus with laser-like single-mindedness on the question of fifths in equal-tempered scales. I hope to talk about other things later.

Clearly \[ \displaystyle{ 2^{7/12} \approx 1.49830707688} \] is remarkably close to 3/2. How well could we approximate the frequency ratio 3/2 if we used an equal-tempered scale with some other number of tones?

For a scale with n tones, this amounts to finding the power of 21/n that comes closest to 3/2. Here's how it works:

\[ \begin{array}{llllcl} \textbf{1-TET} & 2^{1/1} & = & 2.00000 &\; \; & 33.3333\% \\ \textbf{2-TET} & 2^{1/2} & \approx & 1.41421 &\; \; & -5.7191\% \\ & 2^{2/3} & \approx & 1.58740 && +5.8267\% \\ & 2^{2/4} & \approx & 1.41421 && -5.7191\% \\ \textbf{5-TET} & 2^{3/5} & \approx & 1.51572 && +1.1048\% \\ & 2^{4/6} & \approx & 1.58740 && +5.8267\% \\ \textbf{7-TET} & 2^{4/7} & \approx & 1.48599 && -0.9337\% \\ & 2^{5/8} & \approx & 1.54221 && +2.8141\% \\ & 2^{5/9} & \approx & 1.46973 && -2.0177\% \\ & 2^{6/10} & \approx & 1.51572 && +1.1048\% \\ & 2^{6/11} & \approx & 1.45948 && -2.7013\% \\ \textbf{12-TET} & 2^{7/12} & \approx & 1.49831 && -0.1129\% \\ \\ \textbf{29-TET} & 2^{17/29} & \approx & 1.50129 && +0.08629\% \\ \textbf{41-TET} & 2^{24/41} & \approx & 1.50042 && +0.02796\% \\ \textbf{53-TET} & 2^{31/53} & \approx & 1.49994 && +0.00394\% \\ \end{array} \]

At right I show the percentage error of the approximate fifth: for example, 21/2 is 5.7191% less than 3/2. The rows with names have a better perfect fifth than any row above. After 12-TET I got tired of showing you every row, and just showed the scales whose perfect fifth beats all previous scales.

◆ 1-TET is a ridiculous scale that only lets you play octaves, so its best approximate fifth is the octave.

◆ 2-TET also has a terrible approximate fifth: it's 21/2, the tritone, which is extremely dissonant.

◆ 5-TET is surprisingly good for a scale with so few tones, with an approximate fifth just 1.1048% too high. Many different pentatonic scales are used worldwide, but the pentatonic scale called slendro in Javanese and Balinese gamelan music is pretty close to 5-TET.

◆ 7-TET has an approximate fifth that's 0.9337% too low, just a bit better than 5-TET. Oddly I'm having trouble finding examples of music in 7-TET. Apparently it was used in some traditional Chinese music. I'd love to know more details.

◆ Then comes 12-TET, a marked improvement with a fifth that's just 0.1129% too low.

It's impossible not to notice that 5 + 7 = 12, and that our standard use of 12-TET on a piano divides the 12 tones into 5 black keys and 7 white keys.

The black keys form a pentatonic scale, while the white keys form the so-called diatonic scale. Both are widely used in Western music — and in the case of the diatonic scale that's a massive understatement: see my article on modes of the major scale for some ways it's used.

These pentatonic and diatonic scales are significantly different from 5-TET and 7-TET, since their notes are not close to evenly spaced. And yet I can't help but wonder if some faint shadow of 5-TET and 7-TET hangs over 12-TET, and the way we subdivide it into pentatonic and diatonic scales.

Mathematically, it seems to be a sheer coincidence that 5-TET, 7-TET and 12-TET give particularly good fifths and 5 + 7 = 12. But later I'll mention a few more facts that make this fact even more tantalizing!

◆ 29-TET is the next winner: its fifth is just 0.08629% too high. It has been argued that in 1318 the medieval Italian music theorist Marchetto da Padova proposed a system that is approximately 29-TET:

I'll admit I'm not convinced.

◆ 41-TET has a fifth that's just 0.02796% too high. This has been used or at least studied enough to have its own Wikipedia page:

The pianist and engineer Paul von Janko built a piano using this tuning, which is on display at the Gemeentemuseum in the Hague. I recommend looking at the Wikipedia page to see how much more detailed it is than anything I'm saying here. Then look at this:

and see what true devotion looks like! Xenharmonic music is music that uses tuning systems other than 12-TET.

◆ 53-TET is a massive improvement, with a fifth that's only 0.00394% too high, so this scale has been on people's radar for a long time. Wikipedia again has an article on it:

and this time the historical section is interesting enough to quote in detail:

Theoretical interest in this division goes back to antiquity. Jing Fang (78–37 BCE), a Chinese music theorist, observed that a series of 53 just fifths (3⁄253) is very nearly equal to 31 octaves (231). He calculated this difference with six-digit accuracy to be 177147⁄176776. Later the same observation was made by the mathematician and music theorist Nicholas Mercator (c. 1620–1687), who calculated this value precisely as

\[ \displaystyle{ \frac{3^{53}}{2^{84}} = \frac{19383245667680019896796723}{19342813113834066795298816} }\]which is known as Mercator's comma. Mercator's comma has a small value to begin with (≈ 3.615 cents), but 53 equal temperament flattens each fifth by only 1⁄53 of that comma (≈ 0.0682 cent ≈ 1⁄315 syntonic comma ≈ 1⁄344 Pythagorean comma). Thus, 53 tone equal temperament is for all practical purposes equivalent to an extended Pythagorean tuning.

After Mercator, William Holder published a treatise in 1694 which pointed out that 53 equal temperament also very closely approximates the just major third (to within 1.4 cents), and consequently 53 equal temperament accommodates the intervals of 5 limit just intonation very well. This property of 53-TET may have been known earlier; Isaac Newton's unpublished manuscripts suggest that he had been aware of it as early as 1664–1665.

Mercator's observation that 53-TET has a good approximate 'just major third' boils down to the fact that

\[ \displaystyle{ 2^{17/53} \approx 1.24898 }\]

is close to 5/4 = 1.25.

I find all the history here fascinating. Nicholas Mercator is not the guy with the Mercator projection — that was Gerardus Mercator. He's the guy who invented the term 'natural logarithm' and discovered that \[ \displaystyle{ \ln(1 + x) = 1 + x - \frac{x^2}{2} + \frac{x^3}{3} - \cdots }\]

By the way, 'Mercator' just means 'merchant', and Nicholas Mercator's German name was 'Kauffman'. I hope sometime to say more about the work of Mercator and Newton on tuning systems.

By the way, remember my observation that three good scales 5-TET, 7-TET and 12-TET are related by 5 + 7 = 12? After I posted this article, Sylvain pointed out on Mastodon that 29-TET, 41-TET and 53-TET are related by similar formulas! \[ \begin{array}{ccl} 29 &=& 12+12+5 \\ 41 &=& 12+12+12+5 \\ 53 &=& 12+12+12+12+5 \end{array} \]

More coincidences? Or is something deeper at work here? I have no idea!

What's next? Is there a systematic way to get ahold of these equal-tempered scales with good approximate fifths?

Yes: the key is to study the number

since this number x has

so if we find a good rational approximation to x, say

then we get

so in an equal-tempered scale with q tones, the fifth will be close to p tones above the octave.

To find good rational approximations to x we can take its continued fraction expansion... I'll do it using Wolfram Alpha... and get

If we truncate this at some point we get a good rational approximation to x and thus an equal-tempered scale with a good approximate fifth. For example \[ \displaystyle{ \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{1 + \frac{1}{2 + \frac{1}{2}}}} = \frac{7}{12} } \]

This says that 12-TET has a pretty good approximate fifth, and we get it by going up 7 steps on this 12-tone scale.

If we do this systematically we get these rational approximations to x:

1

1/2

3/5

7/12

24/41

31/53

179/306

389/665

9126/15601

18641/31867

46408/79335

65049/111202

111457/190537

6195184/10590737

6306641/10781274

31421748/53715833

100571885/171928773

131993633/225644606

and so on. I thank Chris Grossack for showing me how to compute these using Sage.

This list includes all the 'best so far' equal-tempered scales on my previous list except for 7-TET. It skips straight from 5-TET to 12-TET. Why is that — what's the underlying math here? I imagine there's quite a bit to say, not about this one particular case but about the general theory of approximating numbers by rationals. I know continued fractions give good results, but what about all the other 'best so far' approximations: that is, rational approximations that are better than any with a smaller denominator? Are they common, rare, etc.?

We can also get new scales, using \[ \begin{array}{ccl} 2^{179/306} & \approx & 1.50000501098 \\ 2^{389/665} & \approx & 1.49999990153 \\ 2^{9126/15601} & \approx & 1.50000000175 \\ 2^{18641/31867} & \approx & 1.49999999966 \end{array} \]

and so on.

Of course, this is basically an argument for why you shouldn't let mathematicians get involved with tuning systems. A scale with 306 or more tones is not very practical — and even though we can compose and play music on such scales using computers, the ear will not greatly prefer the fifths in this scale to those in 53-TET.

To be frank, most people are perfectly happy with 12-TET! And I should lay my cards on the table: my overall goal is not to find better tuning systems, but to better understand the math behind the historically most important 12-tone tuning systems. I would like to write about these:

These dates are very rough, and I'd love to find some books that

investigate the history more carefully... but anyway, I'm not sure

I'll even get around to discussing all these systems. But I'd like

to! There is some mildly fancy math that could be brought in, which I

haven't seen people using.

Equal Temperament (Part 2)

When I listed some equal-tempered scales with good perfect fifths (see

my October 15th entry, a

reader named Sylvain

noticed something interesting. The scales with 5, 7, 12, 17, 29, 41

and 53 tones are particularly good, and

$$ \begin{array}{ccl}

17 &=& 12 + 5 \\

29 &=& 12 + 12 + 5 \\

41 &=& 12 + 12 + 12 + 5 \\

53 &=& 12 + 12 + 12 + 12 + 5

\end{array}

$$

I asked if this is a coincidence. And now I know the answer: no, it's not! There really is a reason for this pattern.

As we'll see, part of the reason is that $$ 7/12 \approx 0.58333333333... $$ is very close to $$ \log(3/2)/\log(2) \approx 0.58496250072... $$ But we'll also see it's crucial that 5 × 7 is slightly less than a multiple of 12. As far as I can tell, these coincidences are unrelated.

Surprisingly, the further coincidence that 5 + 7 = 12 seems to play no role here. But of course there are 5 black notes and 7 white notes in the scale on a piano, and that's musically important too! So the music we love, and even the music we could love in equal-tempered scales with more notes, relies on 3 interlocking facts about the numbers 5, 7 and 12.

All this started becoming clear to me when Scott Centoni wrote a little program in Sage to see how good the perfect fifth is in \(N\)-TET (the scale that divides the octave into N equally spaced notes).

When we use logarithms of frequency ratios, log(3/2) is a perfect fifth, while log(2)\(M/N\) is the \(M\)th note in \(N\)-TET. So, one way to formulate the question mathematically is: how well can we approximate log(3/2) by log(2)\(M/N\) for some integer \(M\)?

Alternatively: how well we can approximate log(3/2)/log(2) by a number of the form \(M/N\)?

Scott Centoni graphed the answer to the latter question and got the following:

This graph shows the difference $$ \Delta = M/N - \log(3/2)/\log(2) $$ for the best choice of \(M\) for each \(N\) from \(N = 5\) up to \(N = 65\). For example, take \(N = 12\). Then \(M = 7\) gives the best approximation to \(\log(3/2)/\log(2)\), and $$ \Delta = 7/12 - \log(3/2)/\log(2) \approx -0.00162916742 $$ So, the blue dot labeled 12 is very slightly below the x axis.You'll immediately notice a bunch of nice patterns in this chart. Most exciting to me are the descending bands consisting of either 6 even numbers or 6 odd numbers!

The bands of even numbers almost cross the x axis at multiples of 12, namely \(N\) = 12, 24, 36, 48, 60. The difference \(\Delta\) is the same for all these \(N\). Why? Well, 7/12 is so close to the magic number log(3/2)/log(2) that the best approximation to this magic number of the form \(M\)/24 is just 14/24 = 7/12. The best approximation of the form \(M\)/36 is just 21/36 = 7/12. And so on for quite a while... but not forever.

Also, if you look very carefully, you'll see \({|\Delta|}\) is smaller for \(N\) = 58 than \(N\) = 60. So while multiples of 12 provide the best even choices of N for a while, this doesn't last forever.

After a bit of glitchiness at the start, the bands of odd numbers come close to the x axis at numbers that are 5 more than a multiple of 12, namely 17, 29, 41, 53 and 65. Why? This is a bit more tricky. A good explanation of this was provided by gjm on Mathstodon, and I'll quote it below. Ultimately the reason is that 7 times 5 is almost a multiple of 12... yet that hint will probably seem quite cryptic until you read what gjm wrote.

But first, another visibly obvious pattern: the scales with \(N\) = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30 and 35 notes all have the same Δ. Why? Well, 3/5 is fairly close to the magic number log(3/2)/log(2), so the best approximation to this number of the form \(M\)/10 is 6/10 = 3/5. And so on for a while. But it turns out 21/35 = 3/5 is not as close to the magic number as 20/35, so the pattern breaks down at this point.

You can also see that the scales with \(N\) = 7, 14, 21, 28 and 25 all have the same Δ. The reason is similar: 4/7 is close to the magic number.

Now for gjm's explanation of the bands of even and odd numbers, and further subtleties:

The pattern is a consequence of 7/12 being a good approximation for \(r = \log(3/2)/\log(2)\); there's a little bit less here than meets the eye.Write \(r = 7/12 + h\) where \(h\) is small (it's a little bit smaller than 1/600).

Suppose we're looking at a scale with \(N = 12n + k\) equally-spaced notes. Then the quality of the fifths depends on how close \((12n + k)r\) is to an integer. Well, \[ (12n+k)r = 7n + (7/12)k + (12n+k)h \] Call these terms \(A, B, C\).

\(A\) is always an integer so we can ignore it.

\(B\) mod 1 repeats with period 12. It's zero when \(k=0\), so multiple-of-12 scales are good as long as \(C\) stays small. It's -1/12 when \(k=5\), and \(C\) is positive, so \(N = 12k+5\) scales are also pretty good, though (at least initially) not as good, as long as \(C\) stays small.

When does the pattern break? Well, \(C\) gradually increases as \(N = 12n+k\) does. After it crosses \(1/24\), at \(N = 26\), \(B = -1/12\) becomes better than \(B = 0\); this doesn't break the pattern yet but it means that "29 is better than 36" even though "12 is better than 17". After \(C\) crosses 1/12, at \(N = 52\), \(B = -2/12\) becomes better than \(B = 0\), and this does break the pattern for even \(N\); \(N = 58\) beats \(N = 60\). After \(C\) crosses 3/24 at \(N = 76\), even \(N\) starts beating odd \(N\) again. After \(C\) crosses 2/12 at \(N = 103\), \(B = -3/12\) becomes better than \(B = -1/12\), which breaks the pattern for odd \(N\); \(N = 111\) is better than \(N = 113\).

The prose is a bit dense here, but it very much repays close reading. In particular, why are equal-tempered scales with numbers of tones like $$ \begin{array}{ccl} 17 &=& 12 + 5 \\ 29 &=& 12 + 12 + 5 \\ 41 &=& 12 + 12 + 12 + 5 \\ 53 &=& 12 + 12 + 12 + 12 + 5 \\ 65 &=& 12 + 12 + 12 + 12 + 12 + 5 \end{array} $$

so good? It must be because these numbers times log(3/2)/log(2) are close to integers.

And why is that? Well, 7/12 is a tiny bit smaller than log(3/2)/log(2). So it must be because for n = 1,2,3,4,5 the number 12n + 5 times 7/12 is a tiny bit smaller than an integer. But that's equivalent to saying 5×7/12 is a tiny bit smaller than an integer. And that's equivalent to saying 5×7 is a bit less than a multiple of 12. And that's true: $$ 35 \approx 36 $$ While I'm talking about perfect fifths, I can't resist showing you Scott's similar chart for major thirds:

Now we are seeing how close some fraction of the form \(M\)/\(N\) comes to log(5/4)/log(2), since a major third has a frequency ratio of 5/4. While the patterns are striking, they are quite different than for perfect fifths! Presumably this is because there is no fraction with small denominator coming very close to log(5/4)/log(2).

Note that \(N\) = 53 gives a very good major third as well as a very good perfect fifth.

I also repeated Scott Centoni's analysis for minor thirds:

Now we are seeing how close some fraction of the form \(M\)/\(N\) comes to log(6/5)/log(2), since a minor third has a frequency ratio of 6/5.

If you're curious how Scott Centoni's plot for fifths would continue to equal-tempered scales with larger numbers of notes, here's how it looks for \(N\)-TET from \(N\) = 12 to \(N\) = 100:

and here's how it looks from \(N\) = 100 to \(N\) = 200:

In the first chart one of the 'descending bands of 6 odd numbers' actually has just 5 numbers. In the second chart, where the vertical scale is different, those bands are still there, but they're so steep that it's easier to see ascending bands of numbers.

There's a lot to explore here. But at least we've seen why the number

12 becomes important as soon you get interested in equal-tempered

scales with perfect fifths!

Just Intonation (Part 1)

$$

\begin{array}{lccc}

& \textbf{Pythagorean} && \textbf{just intonation} \\

\textbf{tonic} & 1 &=& 1 \\

\textbf{major 2nd} & 9/8 &=& 9/8 \\

\textbf{major 3rd} & 81/64 &>& 5/4 \\

\textbf{perfect 4th} & 4/3 &=& 4/3 \\

\textbf{perfect 5th} & 3/2 &=& 3/2 \\

\textbf{major 6th} & 27/16 &>& 5/3 \\

\textbf{major 7th} & 243/128 &>& 15/8 \\

\textbf{octave} & 2 &=& 2 \\

\end{array}

$$

In 'Pythagorean tuning’ all the frequency ratios between tones are products of powers of the primes 2 and 3. I explained this system in detail here. Because the largest prime it uses is 3, we say Pythagorean tuning is a form of '3-limit tuning'. One can imagine other forms of 3-limit tuning, though no other is as popular.

Now I want to start talking about '5-limit tuning’, where we allow frequency ratios to be products of powers of 2, 3 and 5.

The most popular form of 5-limit tuning is often called 'just intonation'. Broadly defined, just intonation refers to any form of tuning where the frequency ratios are rational numbers. But in practice people often use this term for the specific 5-limit tuning system shown in the above chart. This system was extremely popular in Renaissance music, but it continues to be important today, especially for string instruments.

It will take me a while to explore the mathematics of just intonation. There's a lot more to say here than for Pythagorean tuning. Having an extra prime to play with opens up many new subtleties!

The first thing to notice is that the 3rd, 6th and 7th notes in the major scale are simpler fractions in just intonation than in Pythagorean tuning — as you can see in the chart above.

This is probably why just intonation became popular. It was invented before 150 AD, when Ptolemy wrote about it in his book Harmonikon. But the even older Pythagorean tuning was great for medieval music, which emphasized fifths. Only when major thirds and sixths became popular in England starting in the 1400s with composers like John Dunstaple, and then spread into the rest of Europe, did just intonation take over!

To oversimplify: as the austere and sometimes rather harsh harmonies of medieval music softened to the sweeter sounds of Renaissance polyphony, the need for a better major thirds and sixths pushed just intonation to the fore. It seems to have dominated music until the 1500s! Then, as Baroque music called for more key changes, the beauty of simple fractions in a single major key was slowly sacrificed in favor of other virtues, leading ultimately to the utter dominance of equal temperament today.

In The Arithmetic of Listening, Kyle Gann writes:

History intervenes and alters musical practice. During the Hundred Years’ War (1337–1453), northern France was intermittently occupied by the English; the Maid of Orleans, Joan of Arc, turned the tide in France’s favor by helping get Charles VII crowned king in 1429, though she was burned at the stake in 1431. Before this highwater mark of the war, however, a great influx of English culture had already invaded France, establishing an English presence at such events as the Council of Constance, which lasted from 1414 to 1418 and reportedly attracted more than seventeen hundred musicians. Unlike the medieval French theorists, who were committed to Pythagoreanism, we have evidence that fifteenth-century English musicians used thirds as consonances in a five-limit tuning. Among other things, an influential English theorist, Walter Odington (fl. 1298–1316), had mentioned in his Summa de speculatione musice that major and minor thirds could be sung as consonances of 5/4 and 6/5, respectively, and that they were frequently so altered in actual practice. Also, the music of early fifteenth-century English composers such as John Dunstaple (c. 1390–1453) was noticeably more triadic than the contemporaneous French style; in the precise words of music historian Margaret Bent, in English music of the time, “3rds often seem to be ends in themselves while in contemporary continental music they are still straining for resolution.” This fuller, more consonant sound was termed “the contenance angloise” by a French contemporary who praised his countryman Guillaume Dufay and Gilles Binchois for adopting it. The English — historically less theoretically inclined than the French — were happily and intuitively filling their music with major thirds all over the place and tuning them nicely. Pythagorean tuning, so theoretically sound, began to seem practically deficient and, perhaps worse than that, old-fashioned.So let's think about those thirds a bit harder! As my chart above shows, the Pythagorean major third vibrates $$ \frac{81}{64} = 1.265625 $$ times as fast as the tonic (the first note in the scale). The just major third vibrates $$ \frac{5}{4} = 1.25 $$ times as fast as the tonic. So, the major third sounds a bit sharper in Pythagorean tuning! You can hear a Pythagorean major third here and a just major third here. If you're like me it may take a while to tell the difference.Under English influence, then, consonant, five-based thirds began to abound in fifteenth-century music throughout Europe. To deal with them required moving from a one-dimensional tuning concept to a two-dimensional one. Pythagorean tuning is one-dimensional: it can be diagrammed as a line of perfect fifths. In five-limit tuning we must weigh and jostle two desirable intervals: the 3/2 fifth and the 5/4 third.

To be precise, the Pythagorean major 3rd vibrates exactly $$ \frac{81/64}{5/4} = \frac{81}{80} = 1.0125 $$ times faster than the just major 3rd. And the major 6th and 7th also vibrate \(81/80\) times as fast in Pythagorean tuning as they do in just intonation! For the major 6th, the reason is that $$ \frac{27/16}{5/3} = \frac{81}{80} $$ while for the major 7th, we have $$ \frac{243/128}{15/8} = \frac{81}{80} $$ So this number, \(81/80\), is a big deal! It's called the 'syntonic comma', and I've already written about it here — it makes other interesting appearances in music.

But the big question is: where do the frequency ratios in just intonation come from? What principles do they follow, besides the fact that they're expressed in terms of powers of 2, 3 and 5?

These questions become even more interesting when we go from the 7-tone major scale to the 12-tone chromatic scale. Then the comparison between Pythagorean tuning and just intonation looks like this: $$ \begin{array}{lccc} & \textbf{Pythagorean} && \textbf{just intonation} \\ \textbf{tonic} & 1 && 1 \\ \textbf{minor 2nd} & 256/243 &<& 16/15 \\ \textbf{major 2nd} & 9/8 &=& 9/8 \\ \textbf{minor 3rd} & 32/27 &<& 6/5 \\ \textbf{major 3rd} & 81/64 &>& 5/4 \\ \textbf{perfect 4th} & 4/3 &=& 4/3 \\ \textbf{diminished 5th} & 1024/729 &<& 64/45 \\ \textbf{augmented 4th} & 729/512 &>& 45/32 \\ \textbf{perfect 5th} & 3/2 &=& 3/2 \\ \textbf{minor 6th} & 128/81 &<& 8/5 \\ \textbf{major 6th} & 27/16 &>& 5/3 \\ \textbf{minor 7th} & 16/9 &=& 16/9 \\ \textbf{major 7th} & 243/128 &>& 15/8 \\ \textbf{octave} & 2 &=& 2 \\ \end{array} $$

This is pretty complicated! But there are a lot of interesting patterns at work here. Whenever the Pythagorean and just intonation frequencies are not equal, the greater one divided by the smaller one equals the syntonic comma, \(81/80\). And can you spot the pattern in the 'greater than' and 'less than' signs?

I will have much more to say about just intonation and 5-limit tuning in posts to come. For now I recommend this:

It has more about the diatonic comma!

Just Intonation (Part 2)

Now let's dive into the beauties

of 5-limit

tuning — that is, tuning systems with frequency ratios that

are products of powers of only the primes 2, 3 and 5:

$$ 2^a\, 3^b \, 5^c , \qquad a,b,c \in \mathbb{Z} $$

We've already tackled 3-limit tuning, where we only got to use the

primes 2 and 3. Since multiplying the frequency by 2 merely raises a

tone by an octave, giving a tone that sounds 'just the same, only

higher', we were freed to focus on powers of 3/2. Multiplying the

frequency by 3/2 raises a tone by a fifth, so we got a diagram called

the circle

of fifths:

A point on this circle is a pitch class: two tones give the same pitch class if and only if their frequencies differ by a power of 2.

This circle shows that going up 6 fifths gets us to almost the same pitch class as going down 6 fifths. They're both very close to the tritone: the pitch class directly opposite our original frequency, 1. Taking advantage of these facts, we obtained the Pythagorean tuning system.

Let's try to mimic this procedure for 5-limit tuning! This gets a lot more interesting. Eventually it leads to a popular tuning system, or group of systems, called 'just intonation'.

Since multiplying the frequency by powers of 2 just changes the pitch by octaves, we can focus on powers of 3/2 and 5/4. As mentioned, the frequency ratio 3/2 is called a 'fifth', or more precisely a 'just perfect fifth'. Similarly, 5/4 is called a 'major third', or more precisely a 'just major third'. So, one way to think about 5-limit tuning is that it goes beyond 3-limit tuning by giving us access to the just major third.

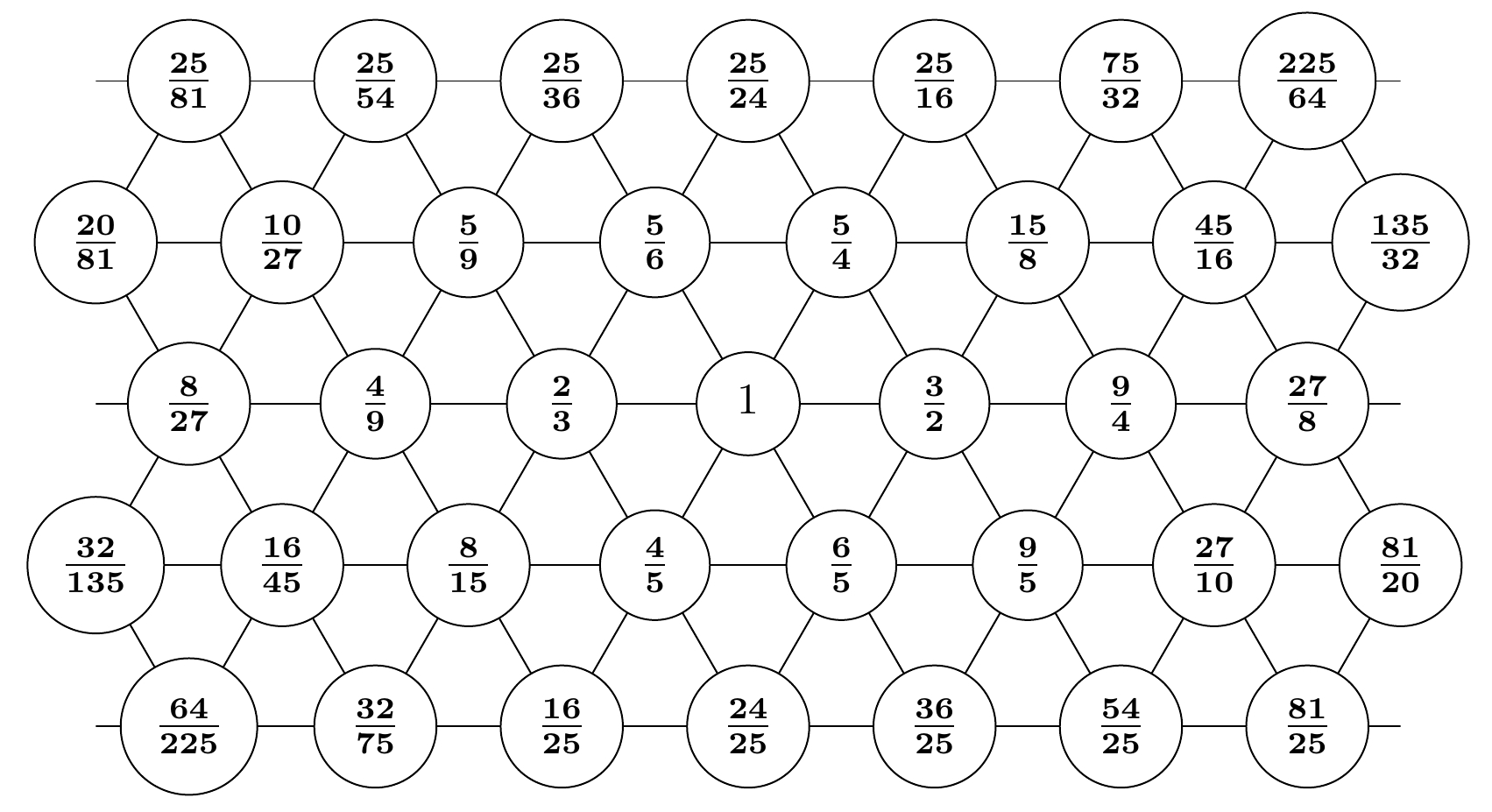

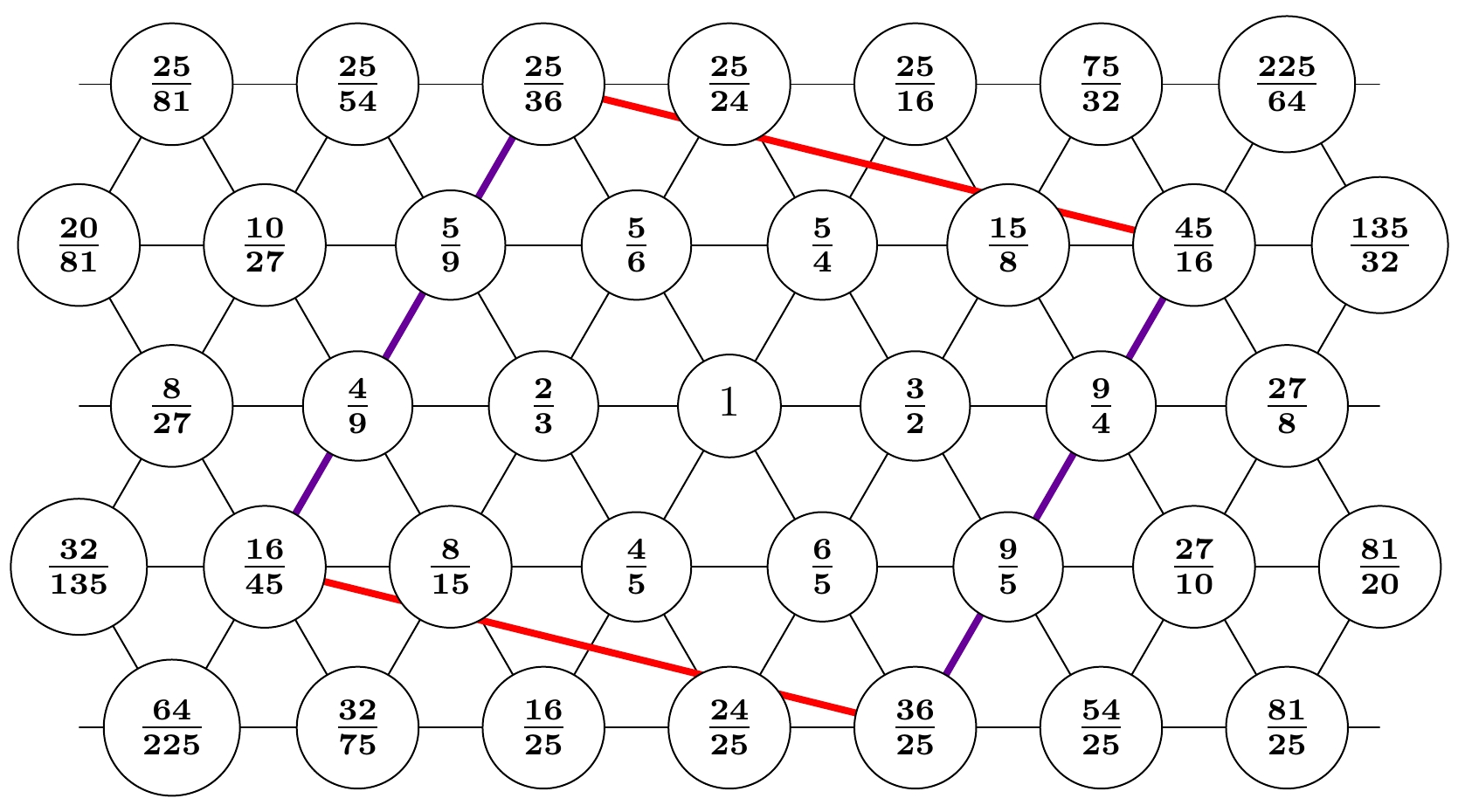

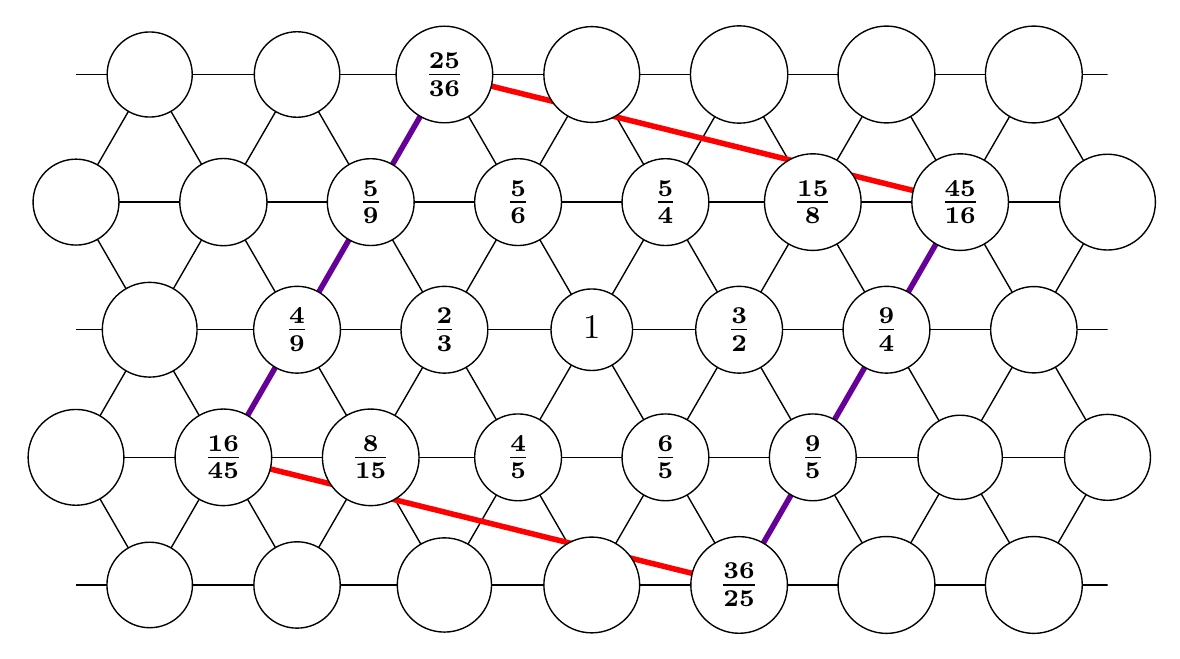

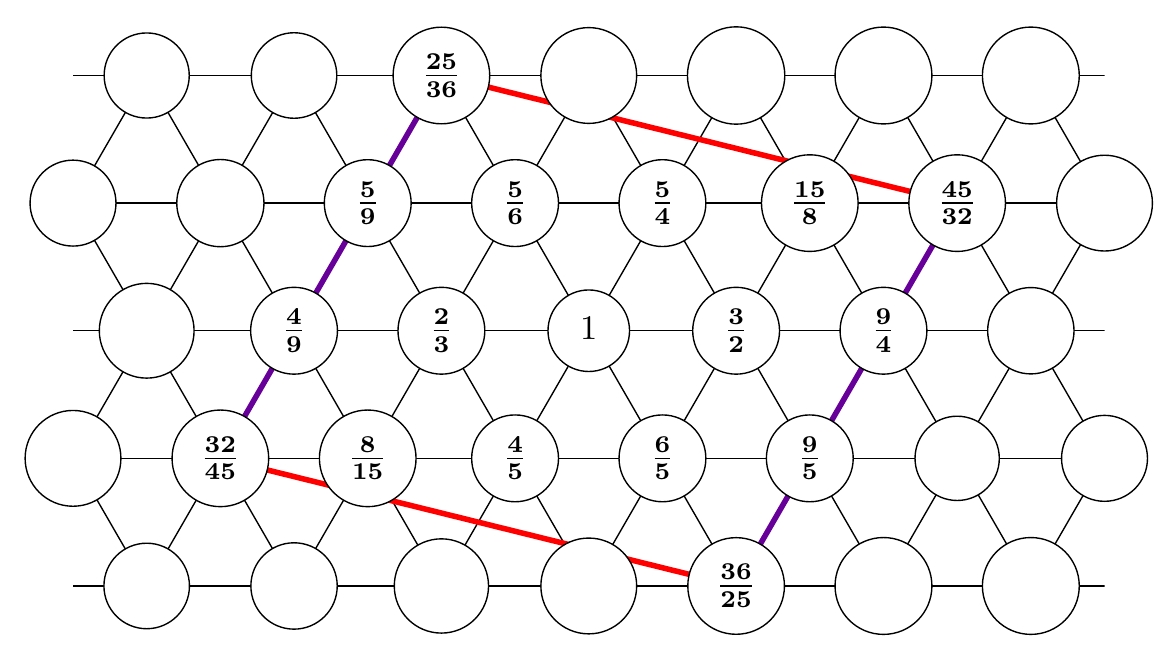

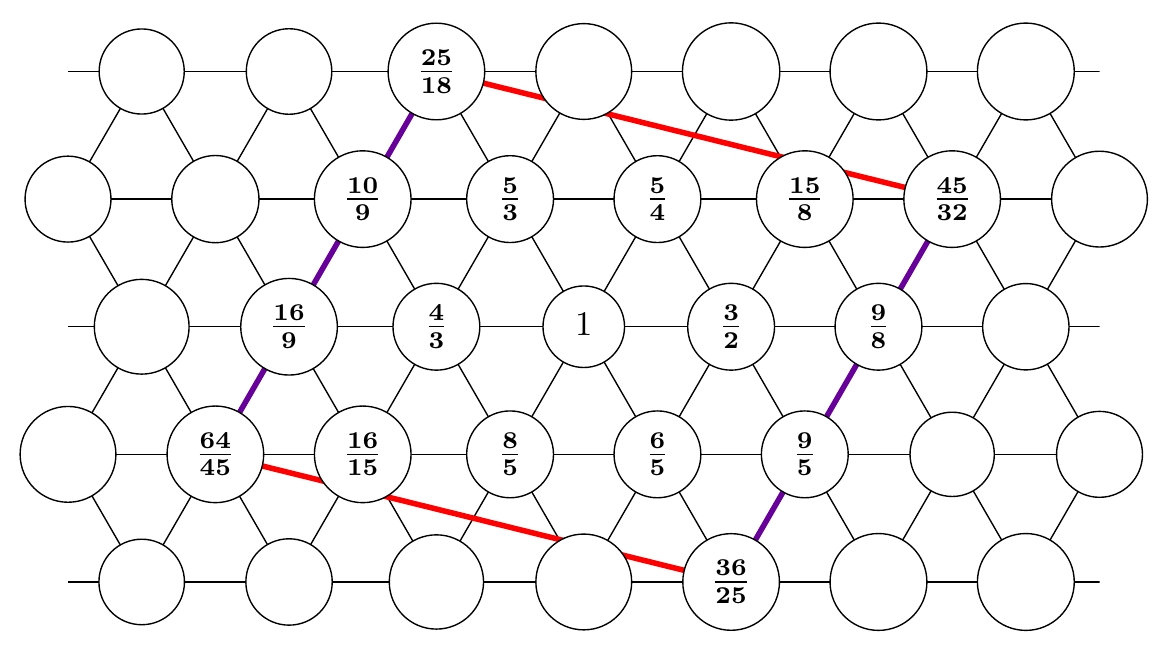

It literally adds an extra dimension! Here we show a lattice with the number 1 at the center, where going one step east multiplies the number by 3/2 and going one step roughly northeast multiplies the number by 5/4:

In musical terms, going one step east takes us up a fifth, while going one step roughly northeast takes us up a third.

Why did I draw a triangular lattice instead of a rectangular one? For now you can think of it as a random artistic decision, but the resulting diagram is called a Tonnetz, which means 'tone network' in German, and later we'll see how useful it is.

Now let's repeat what we did for Pythagorean tuning: let's see how far we have to go before we reach almost the same pitch class in more than one way.

It turns out there are four ways to get very close to the tritone. These four ways are the corners of this parallelogram:

To clean up the picture, let's keep only the tones within this parallelogram (or on its boundary):

Now take these numbers and multiply them by suitable powers of 2 to keep them between 1 and 2. This gives tones lying between the tone at the center of the picture and the tone one octave above, as we'd want for a scale:

Now look at the numbers at the corners of this parallelogram! Let's check that they are close to a tritone, as I claimed. The tritone has frequency $$ \sqrt{2} \; \approx \; 1.414214 \dots $$ The corners are labeled by these numbers: $$ \begin{array}{ccl} \displaystyle{ \frac{25}{18} } &=& 1.38888\dots \\ \\ \displaystyle{ \frac{45}{32} } &=& 1.40625 \\ \\ \displaystyle{ \frac{64}{45} } &=& 1.42222 \dots \\ \\ \displaystyle{ \frac{36}{25} } &=& 1.44 \end{array} $$ So yes, they're pretty close!

Now for the cool part. Suppose we 'wrap around' this parallelogram to get a torus:

We identify the 4 tones on its left edge with the 4 tones on its right edge. Similarly, we identify the 2 tones on the top edge with the 2 tones on the bottom edge. And we're left with 12 tones — great for a 12-tone scale!

It's like magic, how the number 12 shows up yet again.

But there's a problem. The 4 tritones aren't equal, and the 4 numbers on the left edge don't equal the numbers on the right edge. They're close, but not quite equal! This is the same sort of problem that afflicted us in Pythagorean tuning, where we had two candidates for the tritone. But now we get 4 candidates for the tritone, 2 candidates for the major second, and 2 candidates for the minor seventh. So we get a scale with some choices: $$ \begin{array}{ll} \textrm{tonic} & \textrm{1} \\ \textrm{minor 2nd} & \textrm{16/15} \\ \textrm{major 2nd} & \textrm{10/9 or 9/8} \\ \textrm{minor 3rd} & \textrm{6/5} \\ \textrm{major 3rd} & \textrm{5/4} \\ \textrm{perfect 4th} & \textrm{4/3} \\ \textrm{tritone} & \textrm{25/18 or 45/32 or 65/45 or 36/25} \\ \textrm{perfect 5th} & \textrm{3/2} \\ \textrm{minor 6th} & \textrm{8/5} \\ \textrm{major 6th} & \textrm{5/3} \\ \textrm{minor 7th} & \textrm{16/9 or 9/5} \\ \textrm{major 7th} & \textrm{15/8} \\ \textrm{octave} & \textrm{2} \\ \end{array} $$ We need to make some decisions to get a specific scale.

But first, notice that the pattern would be clearer if we hadn't forced our frequencies to lie between 1 and 2 — that is, between the tonic and the octave. It's better if we force them to lie between \(1/\sqrt{2}\) and \(\sqrt{2}\) — that is, between the tritone below the tonic, and the tritone above. Then the Tonnetz has a beautiful symmetry:

For any number in the parallelogram, its reciprocal appears in the opposite position! If we use these numbers instead, we get this nicer table: $$ \begin{array}{ll} \textrm{tritone} & \textrm{25/36 or 32/45} \\ \textrm{perfect 5th} & \textrm{3/4} \\ \textrm{minor 6th} & \textrm{4/5} \\ \textrm{major 6th} & \textrm{5/6} \\ \textrm{minor 7th} & \textrm{8/9 or 9/10} \\ \textrm{major 7th} & \textrm{15/16} \\ \textrm{tonic} & \textrm{1} \\ \textrm{minor 2nd} & \textrm{16/15} \\ \textrm{major 2nd} & \textrm{10/9 or 9/8} \\ \textrm{minor 3rd} & \textrm{6/5} \\ \textrm{major 3rd} & \textrm{5/4} \\ \textrm{perfect 4th} & \textrm{4/3} \\ \textrm{tritone} & \textrm{45/32 or 36/25} \\ \end{array} $$ Now we can start at the tonic and either climb up to the tritone, or climb down to the tritone... using the reciprocals of the same numbers!

Okay, enough perfect mathematical beauty. We have some difficult decisions to make: we have to choose which frequencies we'll actually use for our scale.

Let's recall how it worked for Pythagorean tuning. There we had two choices of tritone. One approach would be to choose both, calling one the augmented 4th and one the diminished 5th. But this gives us a total of 13 tones in our scale! To get a 12-tone scale people typically keep one choice of tritone and discard the other. This causes various difficulties like the 'wolf fifth'.

All these issues become even more complicated in 5-limit tuning, since now we have 4 choices of tritone, 2 choices of major second, and 2 choices of minor seventh. I'll talk about this later.

For now, I just want to point out this. If we only want a major scale, our decisions become much easier: we just need to choose which major 2nd we want! There are just two choices: 10/9 and 9/8. 10/9 is called the small just whole tone and it sounds like this, while 9/8 is called the large just whole tone and it sounds like this.

9/8 is arguably the simpler fraction, and it's the one we used in Pythagorean tuning. If we use 9/8 as our major second we get the following scale, which I'll compare with Pythagorean tuning: $$ \begin{array}{lccc} & \textbf{Pythagorean} && \textbf{just intonation} \\ \textbf{tonic} & 1 && 1 \\ \textbf{major 2nd} & 9/8 && 9/8 \\ \textbf{major 3rd} & 81/64 &>& 5/4 \\ \textbf{perfect 4th} & 4/3 && 4/3 \\ \textbf{perfect 5th} & 3/2 && 3/2 \\ \textbf{major 6th} & 27/16 &>& 5/3 \\ \textbf{major 7th} & 243/128 &>& 15/8 \\ \textbf{octave} & 2 && 2 \\ \end{array} $$ This scale was discussed by Claudius Ptolemy in his famous book Harmonikon roughly around 150 AD, and it's called Ptolemy's intense diatonic scale.

I don't know why it's called 'intense', but this form of just intonation is intensely beautiful. It was very popular from around 1300 (at least in England) to at least 1550 (by which time it had spread to all of Europe). In 1558, in his influential text Le istitutioni harmoniche, the music theorist Gioseffo Zarlino proclaimed that this scale was "the only one that can reasonably be sung" — even though he was busy introducing a more complex tuning system for keyboards, called meantone temperament.

The rise of just intonation from 1300 to 1550 went hand in hand with increased use of major triads, which later became the bread and butter of classical music. A major triad on a tone consists of:

The amazing thing about Ptolemy's intense diatonic scale is that all the notes lie in major triads on the three most important notes in the scale: the tonic, the perfect fourth and the perfect fifth. You can see it in this chart here:

or if you prefer thinking in key of C major:

There are many more questions to answer when we go beyond Ptolemy's intense diatonic scale and construct a chromatic (i.e. 12-tone) scale based on 5-limit tuning. How do we choose between the 4 tritones? How do we choose between the two major 2nds — should we stick with the large just whole tone 9/8, or try the small just whole tone 10/9? How do we choose between the two minor 7ths? And what's the math underlying these choices?

I have a lot to say about this. There's also a lot more to say about

the Tonnetz. But all this will have to wait!

Just Intonation (Part 3)

In the previous section I said a bit about 'just intonation': that is,

tuning where the most important notes have frequency ratios that are

simple fractions. I focused on the historically important case of

'5-limit tuning', where the frequency ratios are products of powers of

primes ≤ 5.

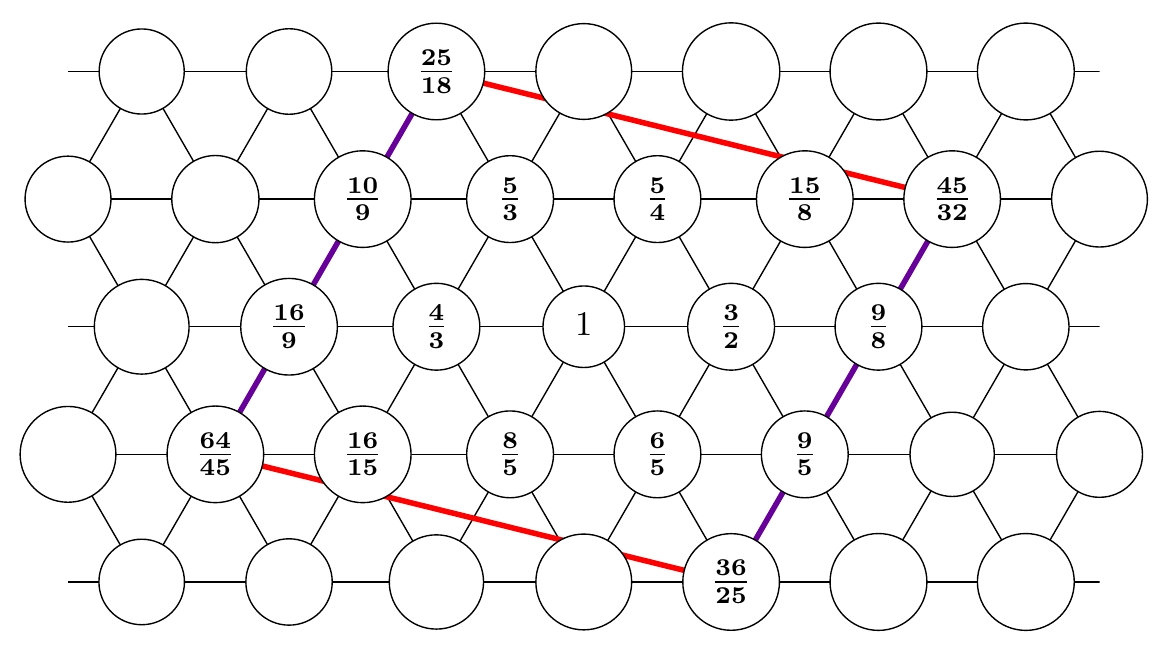

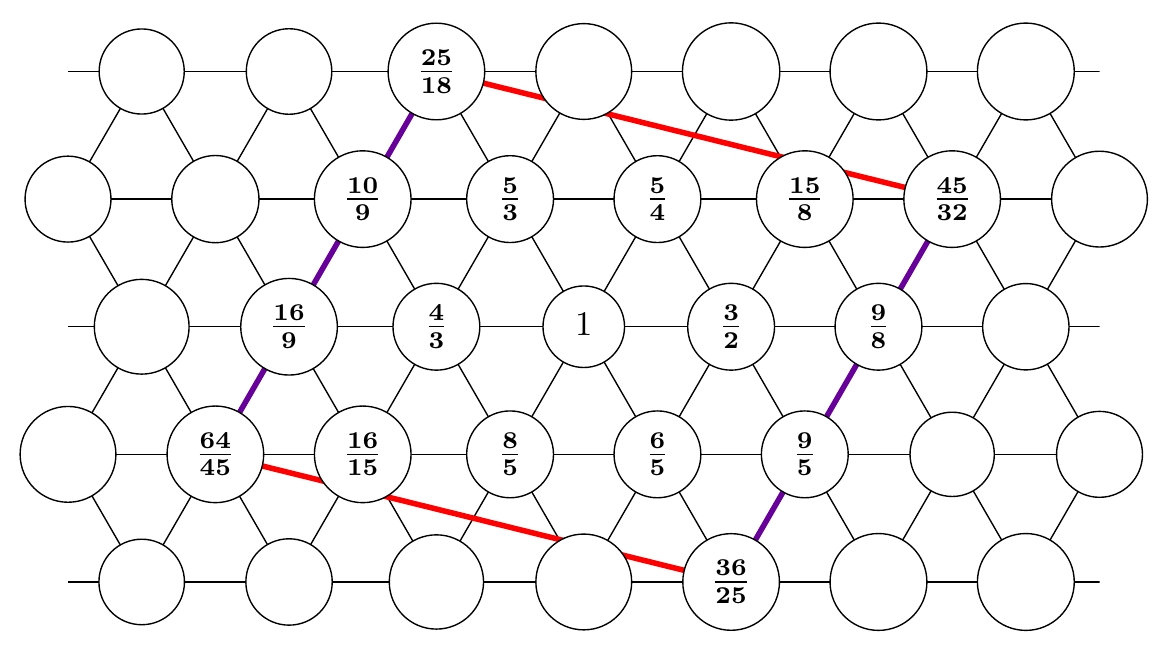

I went a long way toward getting some popular scales in 5-limit tuning. I started by drawing a chart called a 'Tonnetz' where going east multiplies the frequency by 3/2, and going roughly northeast multiplies the frequency by 5/4:

Then, I kept only the numbers in a parallelogram whose corners are numbers very close to a tritone, that is, \(\sqrt{2}\) or \(1/\sqrt{2}\):

Then I multiplied these numbers by appropriate powers of 2 to make them lie between 1 and 2:

If we curl this parallelogram up into a torus, this torus has exactly 12 notes on it! To curl it up, we need to glue each note on the parallelogram's left edge to its partner on the right edge:

We also need to glue each note on the parallelogram's top edge to its partner on the bottom:

The problem is that not all the notes we're gluing together have the same frequency! Luckily, they're close.

How close are these notes, exactly? That's what I want to analyze today. Believe it or not, music theorists have thought about this for thousands of years and made up special terms to describe the answers.

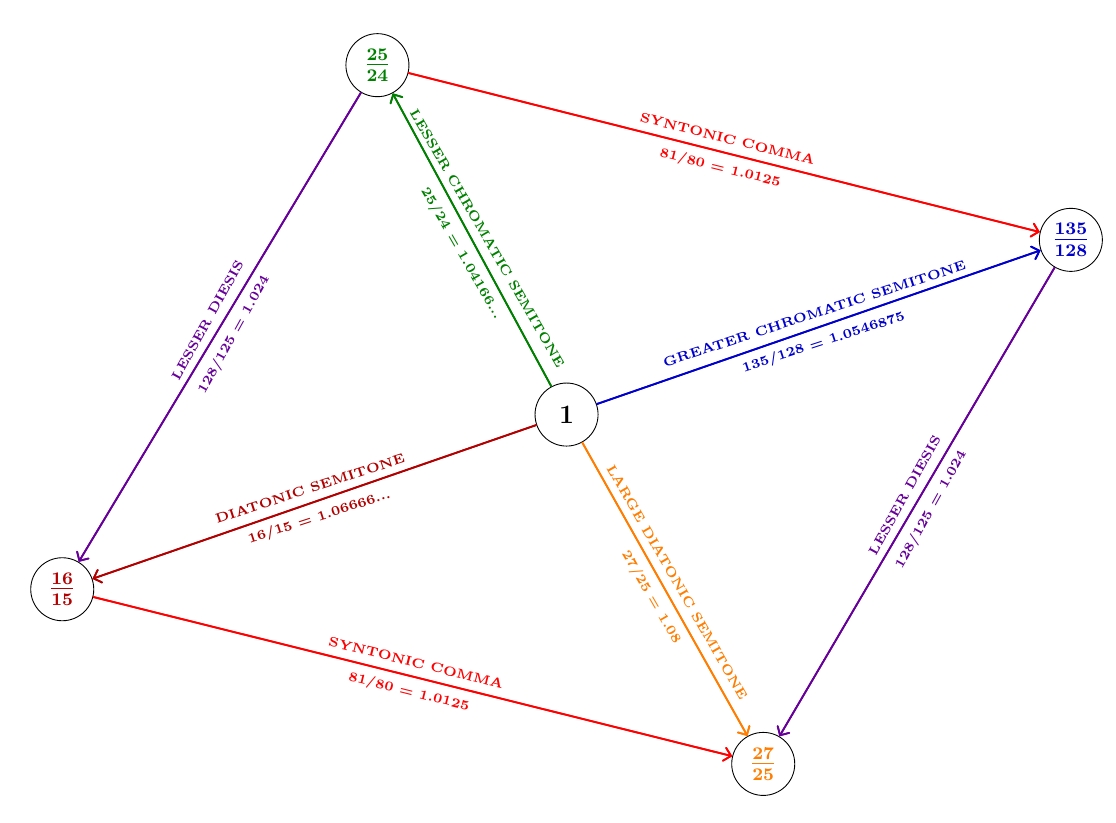

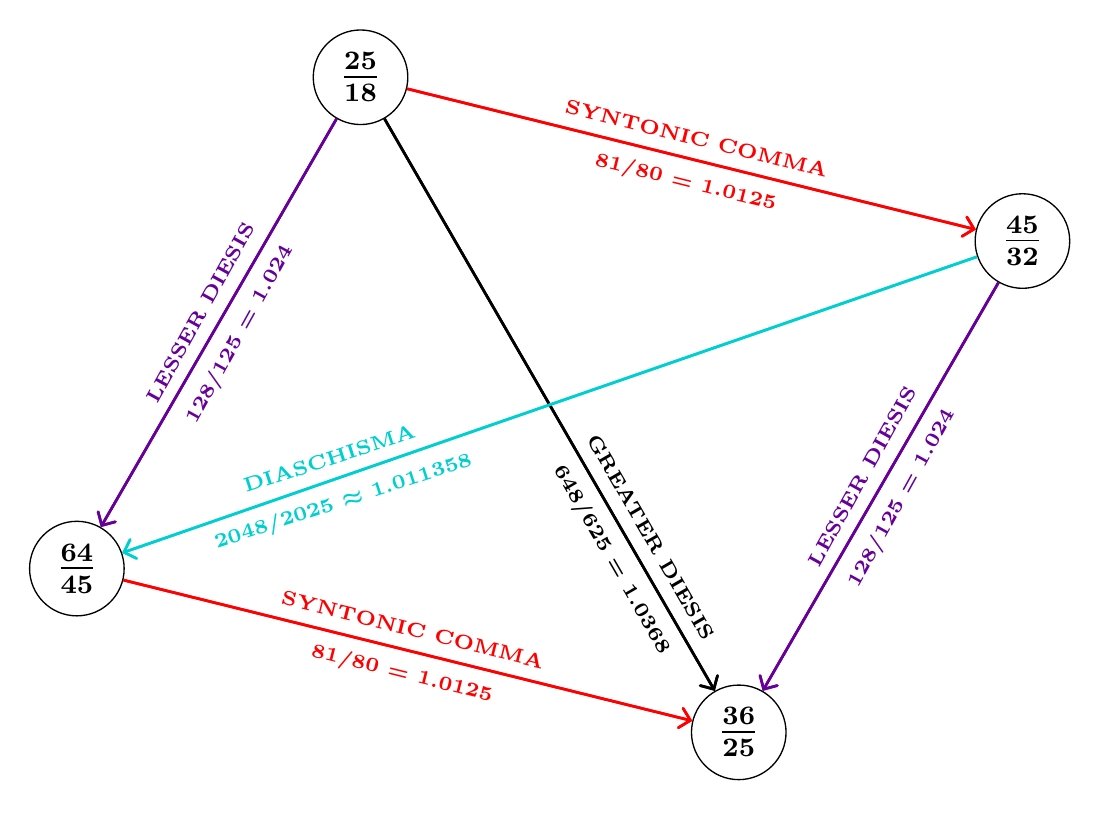

First let's compare the notes on the left edge of the parallelogram to their partners on the right edge:

If we work out their frequency ratios, we see the notes on the right are a bit higher than those on the left: \[ \begin{array}{ccl} \displaystyle{\frac{45/32}{25/18}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{81}{80}} \\ \\ \displaystyle{\frac{9/8}{10/9}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{81}{80}} \\ \\ \displaystyle{\frac{9/5}{16/9}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{81}{80}} \\ \\ \displaystyle{\frac{36/25}{64/45}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{81}{80}} \end{array} \] We always get the same ratio! And it's our friend the syntonic comma: \[ 81/80 = 1.0125 \] This is no accident, of course: it's built into the structure of the Tonnetz. In music terminology, when we go up 4 just perfect fifths and then go down a just major third and 2 octaves, the frequency gets multiplied by \[ 3/2 \times 3/2 \times 3/2 \times 3/2 \times 4/5 \times 1/2 \times 1/2 = 81/80 \] which is the syntonic comma.

So: curling up the parallelogram means deciding whether to use tones on the its left edge and tones on its right edge — which forces us into the jaws of the syntonic comma.

Next let's compare the notes on the top edge of the parallelogram to their partners on the bottom edge:

If we work out their frequency ratios, we see the notes on the bottom are a bit higher than their partners on the top: \[ \begin{array}{ccl} \displaystyle{\frac{64/45}{25/18}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{128}{125}} \\ \displaystyle{\frac{36/25}{45/32}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{128}{125}} \end{array} \] Yet another glitch! This number is called the lesser diesis: \[ 128/125 = 1.024 \] 'Diesis' is a Greek word meaning 'leak' or 'escape' — though 'glitch' might be a more idiomatic translation. In music terminology, if you go up an octave and then go down 3 just major thirds, the frequency gets multiplied by \[ 2 \times 4/5 \times 4/5 \times 4/5 = 128/125 \] which is the lesser diesis. You can see how this works by staring at the Tonnetz.

In short, when we curl up the parallelogram we have some choices to make concerning the major second, the tritone and the major seventh: \[ \begin{array}{ll} \textrm{tonic} & \textrm{1} \\ \textrm{minor 2nd} & \textrm{16/15} \\ \textrm{major 2nd} & \textrm{10/9 or 9/8} \\ \textrm{minor 3rd} & \textrm{6/5} \\ \textrm{major 3rd} & \textrm{5/4} \\ \textrm{perfect 4th} & \textrm{4/3} \\ \textrm{tritone} & \textrm{25/18 or 45/32 or 65/45 or 36/25} \\ \textrm{perfect 5th} & \textrm{3/2} \\ \textrm{minor 6th} & \textrm{8/5} \\ \textrm{major 6th} & \textrm{5/3} \\ \textrm{minor 7th} & \textrm{16/9 or 9/5} \\ \textrm{major 7th} & \textrm{15/8} \\ \textrm{octave} & \textrm{2} \\ \end{array} \] For the major second we have two choices whose ratio is the syntonic comma: 10/9 and 9/8. In a symmetrical way, for the minor seventh below the tonic we have two choices whose ratio is the syntonic comma: 8/9 and 9/10. But we multiply these choices by 2 to get choices for the minor seventh above the tonic: 16/9 and 9/5.

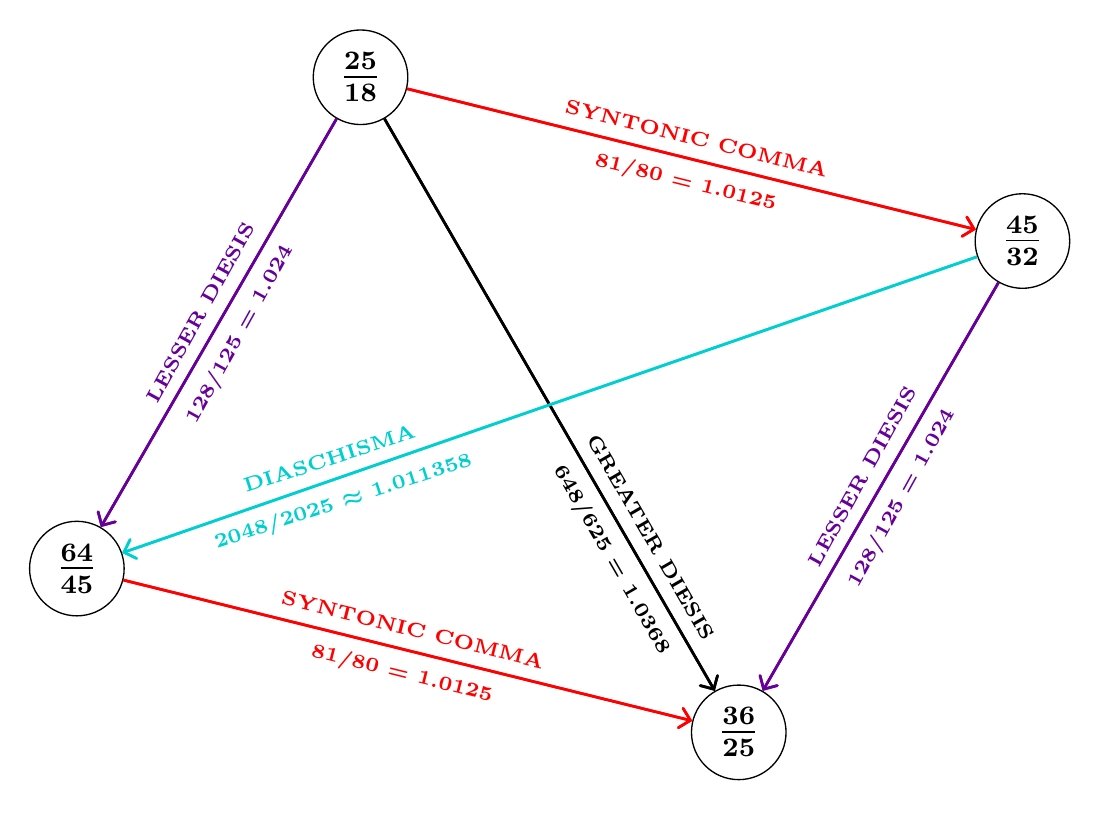

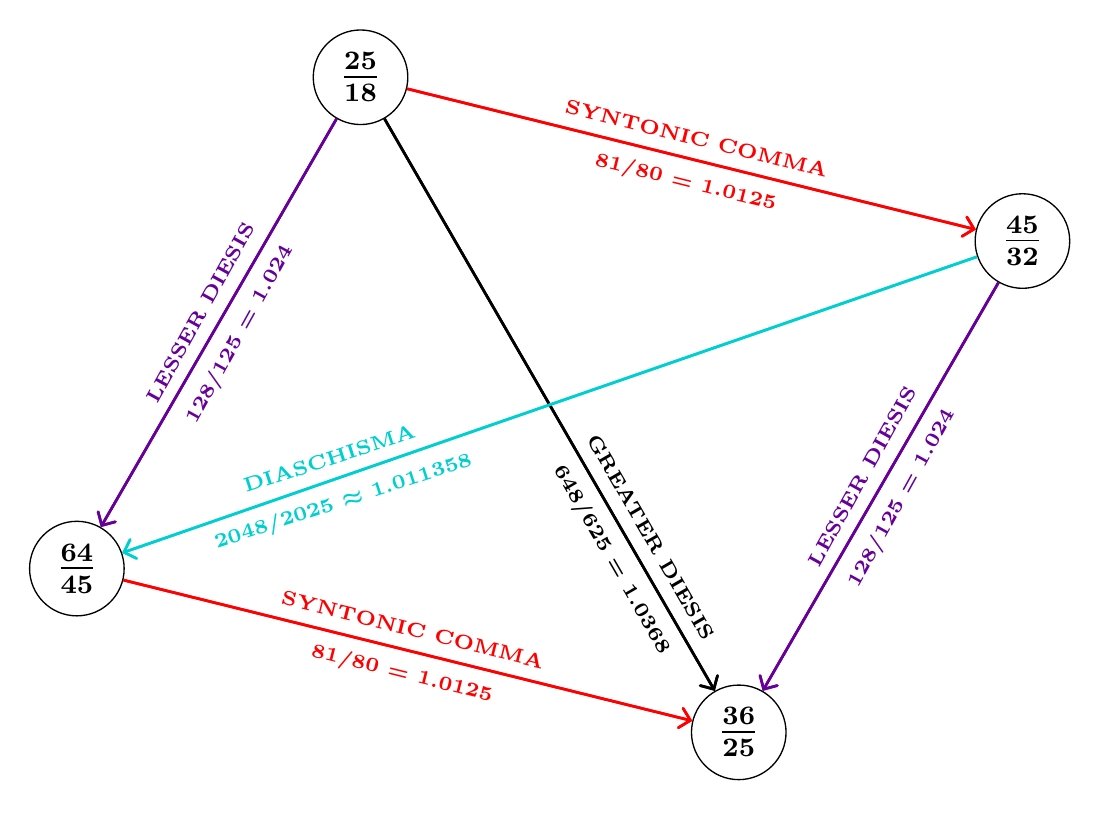

The biggest challenge involves the tritone, where we have four choices, coming from the corners of our parallelogram:

Here I've drawn arrows from lower tones to higher tones, and labeled each edge by the frequency ratio between the tones it connects.

The top and bottom edges have a frequency ratio of a syntonic comma, 81/80, while the left and right edges have a frequency ratio of a lesser diesis, 128/125. The diagonals also have standard names!

The diagonal from upper left to lower right gives a frequency ratio called the greater diesis: \[ \frac{36/25}{25/18} = \frac{648}{625} = 1.0368 \] In other words,

The diagonal from the upper right to the lower left gives a frequency ratio called the diaschisma: \[ \frac{64/45}{45/32} = \frac{2048}{2025} \approx 1.011358\dots \] In other words,

Apparently the diaschisma got its name from the physicist Helmholtz, but it was already studied by Boethius, who wrote a book called De musica in 510 AD. 'Schisma' means something like 'split', so I guess 'diaschisma' means 'the split between'.

Here you can see the syntonic comma, lesser and greater diesis, and diaschisma in decimals, to make it easier to compare how big they are:

Sometimes the tritone is called diabolus in musica — 'the devil in music'. The usual explanation is that this frequency ratio is so dissonant. But as we've seen, it's also devilishly difficult to deal with in just intonation! We have four choices. What should we do?

Stay tuned for more!

Just Intonation (Part 4)

We've seen that there are some choices required when trying to pick a

12-note scale in just intonation:

| tonic | 1 | |

| minor 2nd | 16/15 | |

| major 2nd | 10/9 or 9/8 | |

| minor 3rd | 6/5 | |

| major 3rd | 5/4 | |

| perfect 4th | 4/3 | |

| tritone | 25/18 or 45/32 or 64/45 or 36/25 | |

| perfect 5th | 3/2 | |

| minor 6th | 8/5 | |

| major 6th | 5/3 | |

| minor 7th | 16/9 or 9/5 | |

| major 7th | 15/8 | |

| octave | 2 |

Theoretically, there are

choices. But one is more popular than all the rest — at least in theory. Today I want to talk about that.

Beware: the heyday of just intonation was the Renaissance, but we have rather little information about the actual everyday practice of tuning back then. I wouldn't be surprised if many performers didn't give a fig about these numbers. What we mainly have is writings of theorists. They certainly knew their math. But I have not yet identified a passage in those old theoretical writings where someone commits to a specific 12-tone scale in just intonation. Quite possibly I haven't dug deep enough yet.

When I look around for such scales, modern authors tend to give this one:

| tonic | 1 | |

| minor 2nd | 16/15 | |

| major 2nd | 10/9 or 9/8 | |

| minor 3rd | 6/5 | |

| major 3rd | 5/4 | |

| perfect 4th | 4/3 | |

| tritone | 25/18 or 45/32 or 64/45 or 36/25 | |

| perfect 5th | 3/2 | |

| minor 6th | 8/5 | |

| major 6th | 5/3 | |

| minor 7th | 16/9 or 9/5 | |

| major 7th | 15/8 | |

| octave | 2 |

What's so good about this one?

First, 9/8 is a lot better than 10/9 for the major 2nd. We need it if we want all the notes in the major scale to lie in triads with frequency ratios 1 : 1.25 : 1.5. In C major these triads look like this:

Here the all-important 9/8 shows up as 9/4 since it's an octave up. And the chord in blue, containing the 9/4, has been incredibly important in western music ever since the Renaissance. You tend to play it right before the last chord in a piece of music! It's so bloody important that it has its own special name: the dominant chord.

Second, why should we pick 16/9 for the minor 7th instead of 9/5?

There could be valid musical reasons, but I don't know a compelling one, so I'll retreat to mathematics — a subject I actually know — and point out that this choice gives a scale that's symmetrical. That is, for each frequency in the scale, its reciprocal is also in the scale!

Now you may argue that this is baloney: the reciprocal of 16/9 is 9/16, and that's not on this list:

| tonic | 1 | |

| minor 2nd | 16/15 | |

| major 2nd | 9/8 | |

| minor 3rd | 6/5 | |

| major 3rd | 5/4 | |

| perfect 4th | 4/3 | |

| tritone | 45/32 | |

| perfect 5th | 3/2 | |

| minor 6th | 8/5 | |

| major 6th | 5/3 | |

| minor 7th | 16/9 | |

| major 7th | 15/8 | |

| octave | 2 |

True. You got me there! But 9/16 is just 9/8 divided by 2, which is on the list. Multiplying or dividing a frequency by a power of 2 gives another frequency in the same 'pitch class': they only differ by octaves. So musicians would say 9/16 really is in the scale, just an octave down.

In fact, the symmetry I'm talking about becomes a lot clearer if we list the tones in our scale going both up from the tonic and down from the tonic:

| perfect 5th | 3/4 | |

| minor 6th | 4/5 | |

| major 6th | 5/6 | |

| minor 7th | 8/9 | |

| major 7th | 15/16 | |

| tonic | 1 | |

| minor 2nd | 16/15 | |

| major 2nd | 9/8 | |

| minor 3rd | 6/5 | |

| major 3rd | 5/4 | |

| perfect 4th | 4/3 | |

Look: for each number on the list, its reciprocal on the list! Even better, the reciprocal of any 'major' tone is a 'minor' one, and vice versa. So flipping this scale upside down by taking reciprocals switches major and minor!

This is not a mere curiosity: it's a profound musical fact. Major is 'happy', minor is 'sad', and flipping one upside down gives the other... just like flipping a smile upside down gives a frown.

But you'll notice that to achieve this beautiful symmetry I left out the tritone. In fact, no single one of our original four choices of tritone:

gives a symmetrical scale. The reason is simple: none of these numbers is twice its reciprocal. To achieve that, we'd need to let the frequency of tritone be \(\sqrt{2}\). But that would be irrational.

So, people who want a symmetrical scale get it by choosing two tritones! They usually choose these two, which are reciprocals up to a factor of 2:

They call the smaller one the 'augmented 4th', and the larger one the 'diminished 5th'. Then we get a scale with this beautiful symmetry:

| diminished 5th | 32/45 | |

| perfect 5th | 3/4 | |

| minor 6th | 4/5 | |

| major 6th | 5/6 | |

| minor 7th | 8/9 | |

| major 7th | 15/16 | |

| tonic | 1 | |

| minor 2nd | 16/15 | |

| major 2nd | 9/8 | |

| minor 3rd | 6/5 | |

| major 3rd | 5/4 | |

| perfect 4th | 4/3 | |

| augmented 4th | 45/32 | |

Alas, we got this beautiful symmetry at the expense of having a 13-tone scale with two tones very close to each other. If we want 12 tones, we need to discard one. People usually discard the diminished 5th and keep the augmented 4th, namely 45/32.

Why? I'm not sure, but as a mathematician I'll note that the other choice gives a scale that's just an upside-down version of the scale people usually choose. So, I don't lose much by following the usual convention.

So there we are! We've made our choices as best we can. And since tuning theory is all about frustration, sticking to this approach gives us two choices, neither entirely pleasing:

and

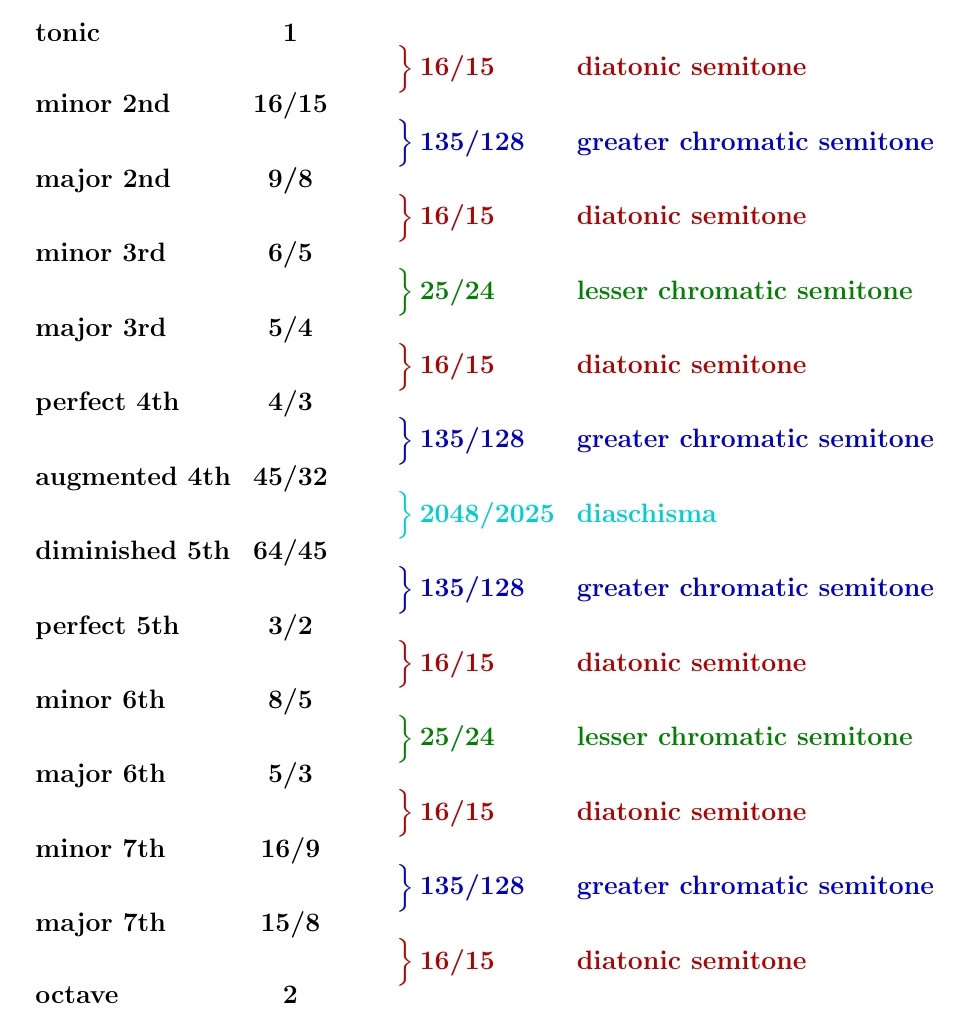

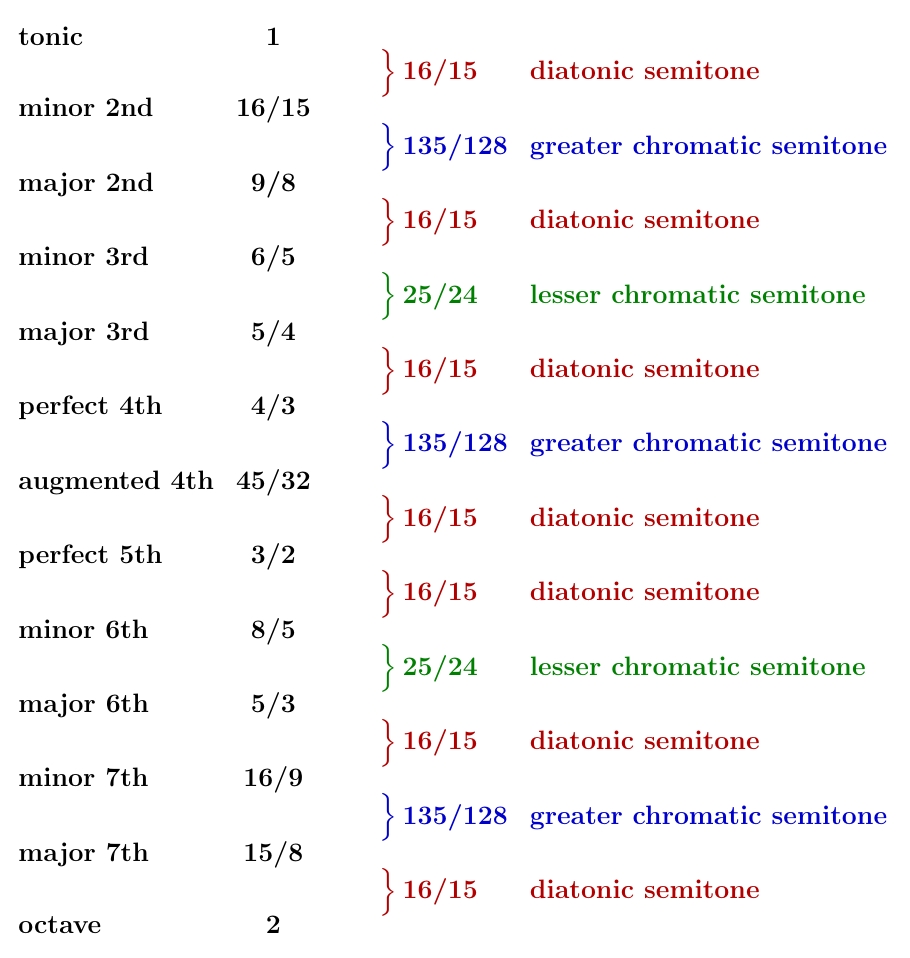

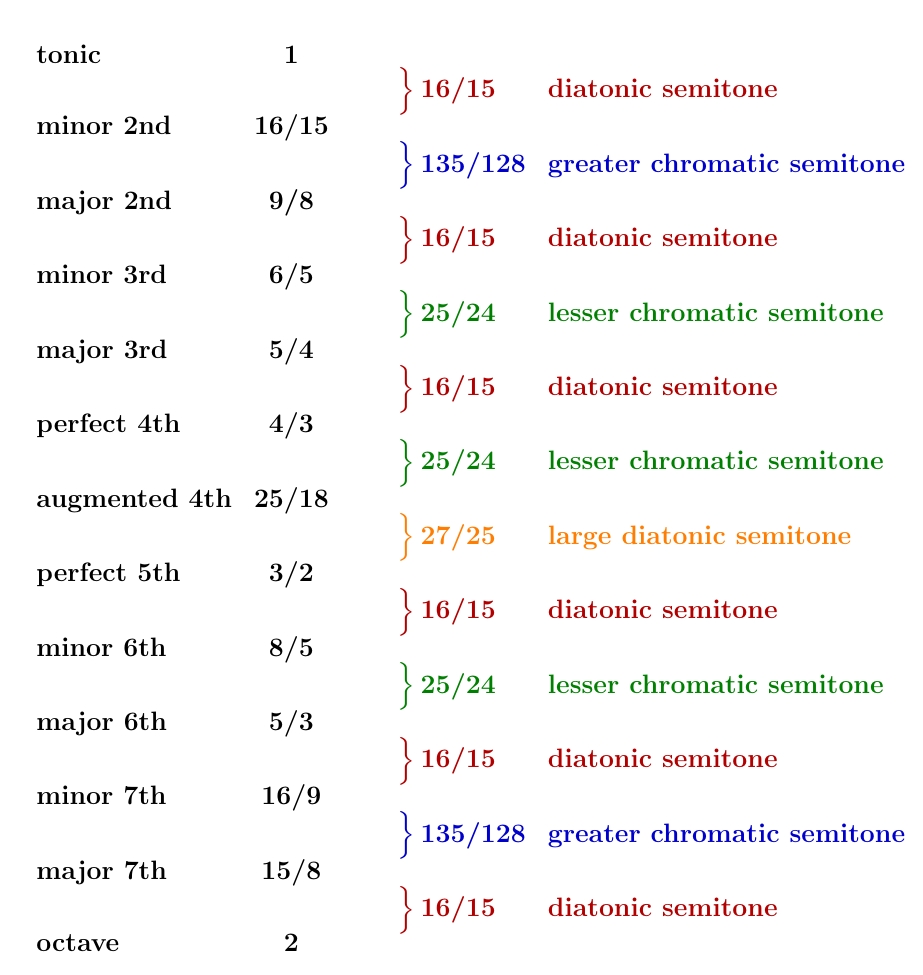

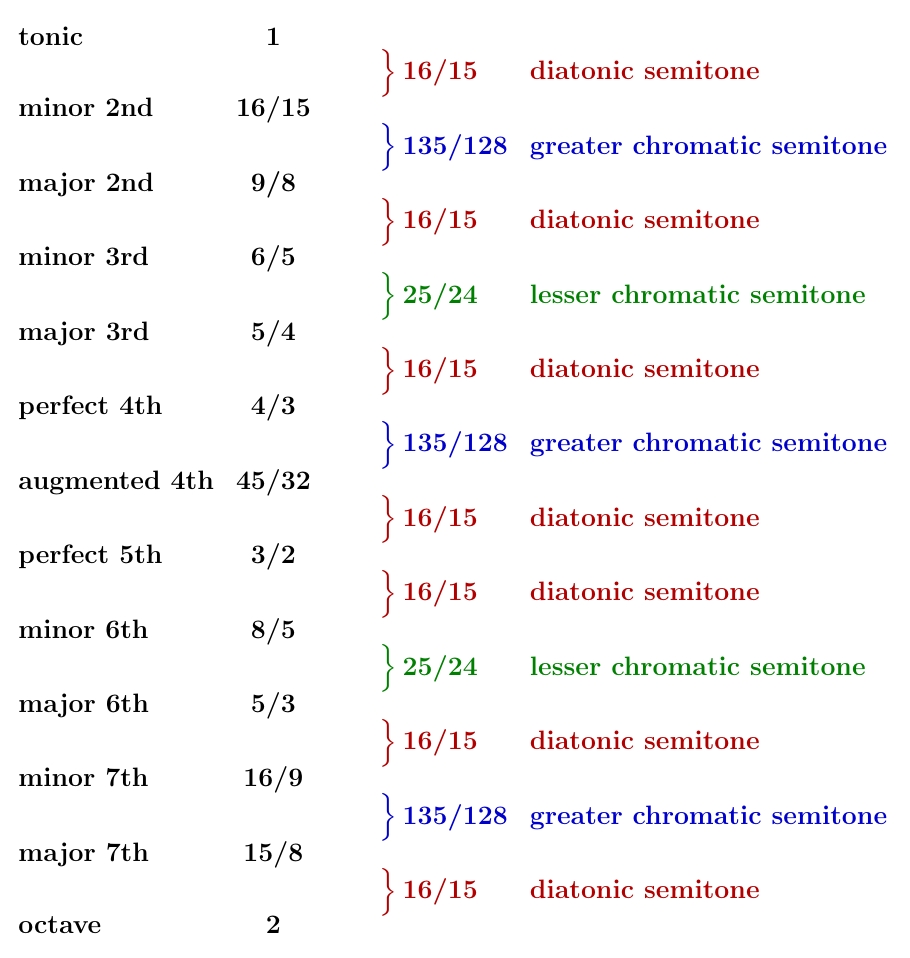

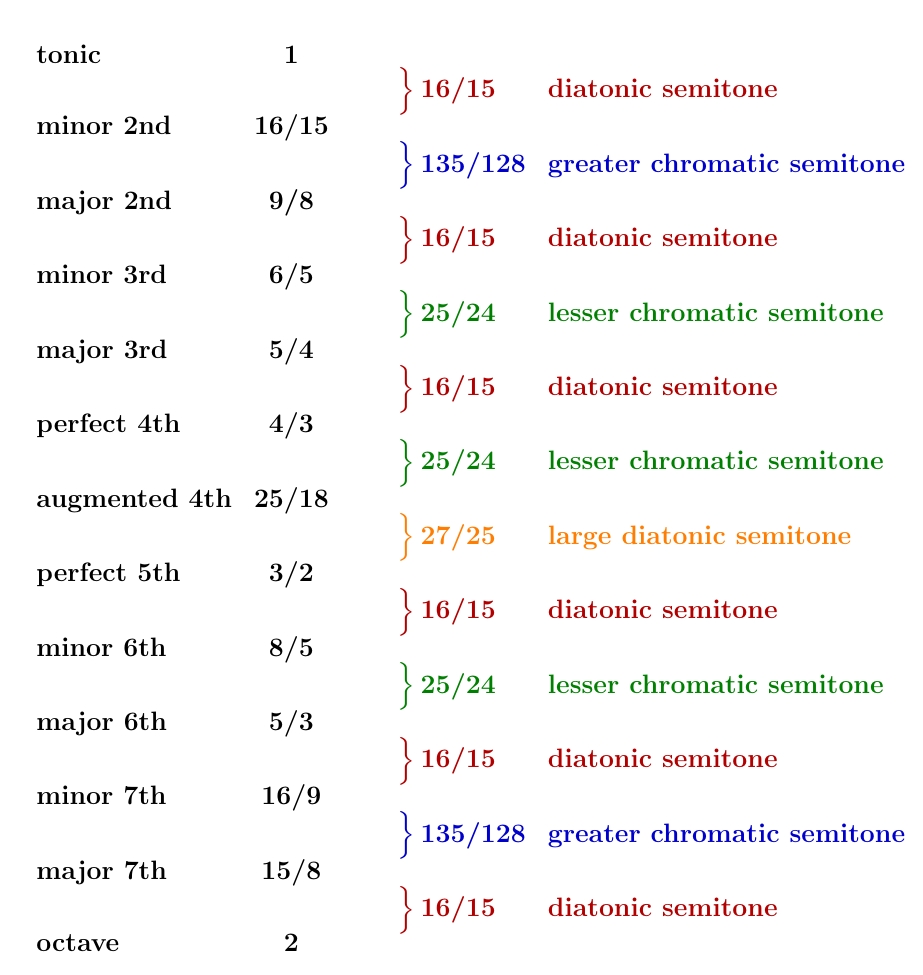

Now let's examine each of these choices in more detail! I want to look at the spacings between the notes. Of course they are not equal: that only happens in equal temperament. But as you might expect, they have cool names. People have been studying this stuff for a long time.

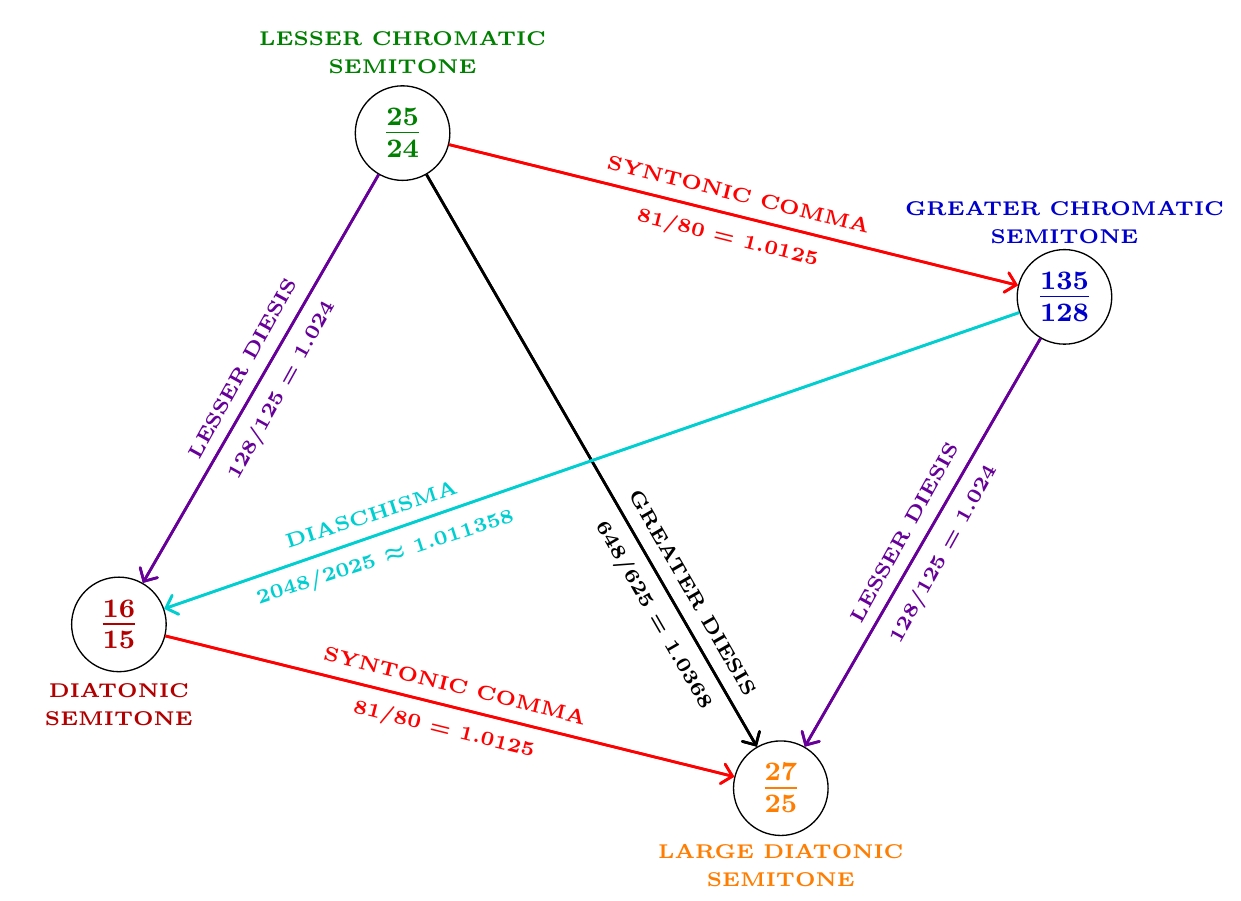

Note that this scale has a beautiful up-down symmetry, as advertised!

There are four kinds of spacings between notes. Three are close to the usual spacing between notes on an equal-tempered piano. They're called half-tones, or semitones:

Our scale also has a tiny space between the augmented 4th and diminished 5th:

I discussed the diaschisma in Part 3, along with all the other tiny intervals between the four choices of tritone in just intonation:

Now you can see why Boethius grappled with the diaschisma as early as 510 AD, though it was named much later by the great mathematician and physicist Helmholtz.

Here's another picture of our scale, which also shows the tones not chosen, in gray:

The up-down symmetry is very visible here.

But what if we create a 12-tone scale by removing the diminished 5th, as people seem to usually do? Then we break the up-down symmetry, and get this scale:

This seems to be the most popular 12-tone just intonation scale. For example, it was favored by Newton and Mersenne.

Compared to the symmetrical 13-tone scale it's based on, this scale has an extra diatonic semitone. There's a reason for that: when we discard the diminished 5th and jump all the way from the augmented 4th to the 5th, we stick the diaschisma onto one of the greater chromatic semitones we had. This gives a diatonic semitone, since

or in terms of numbers: $$ \displaystyle{ \frac{16}{15} = \frac{135}{128} \times \frac{2048}{2025} } $$

Okay, we have reached a natural stopping point for today. I have described the most popular 12-tone scale that uses just intonation! We have seen the frequencies of all its notes. We have also studied the spaces between its notes. What more could we want?

Well, remember that we chose two of the four possible tritones to be the augmented 4th and diminished 5th, namely these:

What if we chose the other two? We'd get another symmetrical 13-tone scale, and discarding its augmented 5th we'd get another 12-tone scale. What's wrong with that scale?

It actually is worse in some objective sense. But to see how, we need to look at it!

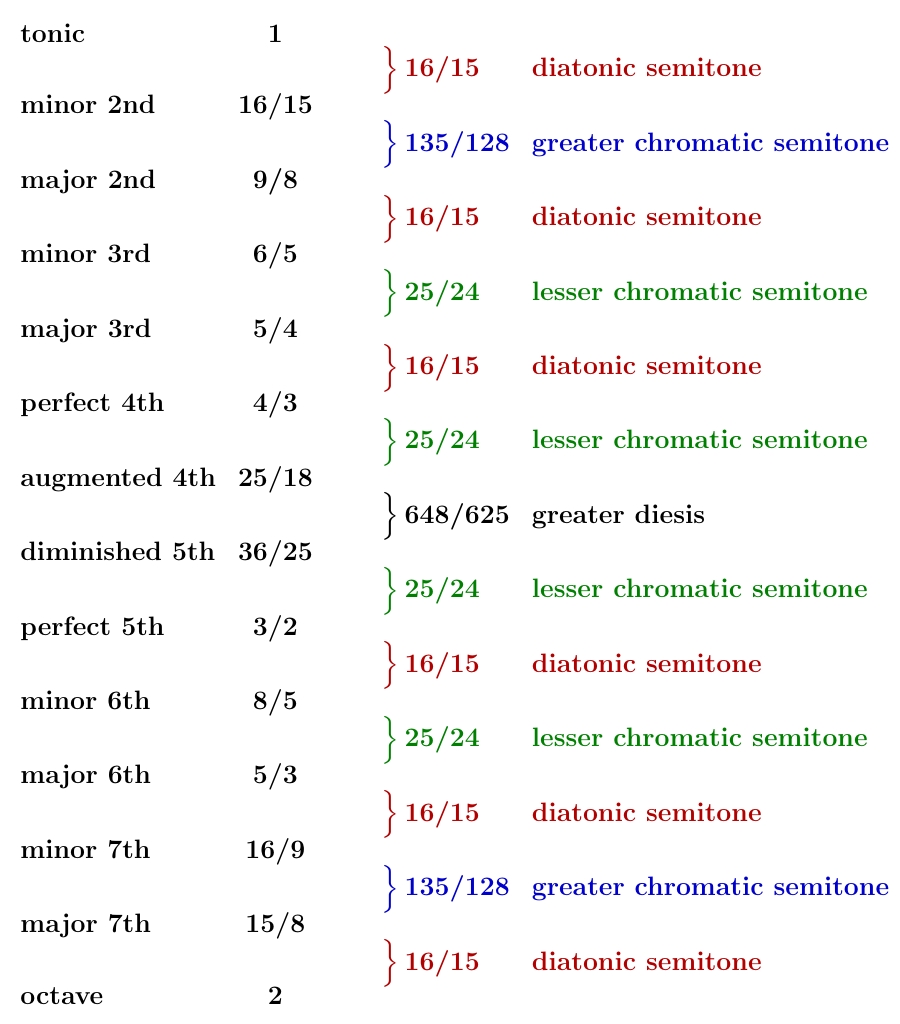

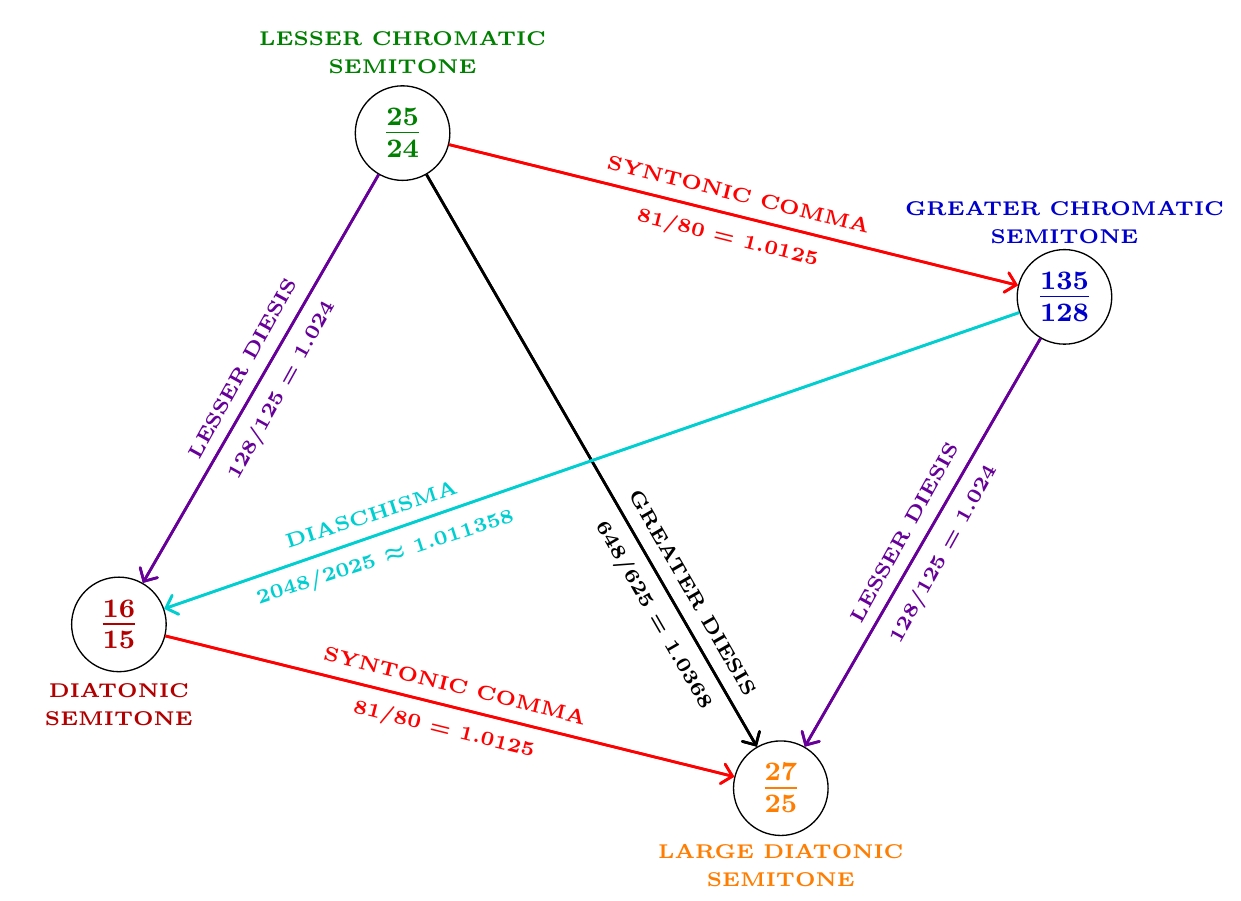

So, let's create a symmetrical 13-tone scale where we use the other two tritones as our augmented 4th and diminished 5th:

It looks like this:

Now the space between the augmented 4th and diminished 5th is bit bigger! It's changed from the diaschisma to a larger interval:

The two neighboring spaces have therefore shrunk. In fact they've shrunk from greater chromatic semitones to lesser chromatic semitones, since

or in terms of numbers:

$$ \displaystyle{ \left(\frac{135/128}{25/24}\right)^2 = \frac{648/625}{2048/2025} } $$

Wild!

This scale doesn't look worse than our other symmetrical 13-tone scale: at least, not to me. It's when we create a 12-tone scale by discarding the diminished 5th that something funny happens.

Let's do it: let's throw out the diminished 5th! Then we get this scale:

Look! Not only does it lack up-down symmetry, as we expect — there's something else odd about it. It has four kinds of semitone! Yes: it has the three we've already seen, but also this:

This is significantly bigger than the other three semitones. And it's nasty to have to keep track of yet another kind of semitone. So, arguably, this scale is not as nice as the one people actually settled on. But the large diatonic semitone is still significant in music theory. Since we got it by sticking the greater diesis onto a lesser chromatic semitone, we get:

or in terms of numbers:

$$ \displaystyle{ \frac{27}{25} = \frac{25}{24} \times \frac{648}{625} } $$

By the way: if you find it impossible to remember these crazy numbers and the web of mathematical relations connecting them, don't feel bad. So do I! Next time I'll summarize all these mathematical relations using some pretty pictures.

Puzzle 1. As we've seen, the most popular 12-tone just intonation scale has 7 diatonic semitones, 3 greater chromatic semitones, and 2 lesser chromatic semitones:

By permuting these semitones we can get many other scales. How many different scales can we get this way?

Puzzle 2. Our second, less popular almost symmetrical 12-tone just intonation scale has 6 diatonic semitones, 2 greater chromatic semitones, 3 lesser chromatic semitones and 1 large diatonic semitone:

How many other scales can we get by permuting these semitones?

Of course these questions are warmups for a bigger question:

Puzzle 3. How many 12-tone scales are there where the spacing between each pair of successive notes is either a diatonic semitone, a greater chromatic semitone, a lesser chromatic semitone or a large diatonic semitone?

These alternative scales may seem pointless, but in fact some have been studied by famous music theorists or mathematicians. For example, in 1694 William Holder discussed a scale with 5 lesser chromatic semitones, no greater chromatic semitones, 4 diatonic semitones and 3 large diatonic semitones!

(For answers to these puzzles see Part 6.)

Just Intonation (Part 5)

In Part 2 we saw that in just

intonation there are four candidates for

the tritone. They

are simple fractions close to the square root of 2. We saw that they

lie at the corners of a parallelogram in a diagram called the tone

network, or Tonnetz:

To get a 12-tone scale from this parallelogram, we need to think about the tiny differences between these 4 numbers. More precisely, since our ear hears frequency ratios, we need to think about the ratios of these 4 numbers, which are close to 1. Because people have been thinking about them for centuries, they all have cool names:

Here I've drawn arrows from tones of lower frequency to tones of higher frequency, and labeled these arrows by the frequency ratios.

In Part 4 we studied how to get a 12-tone scale in just intonation. I described two ways. In the most popular way, the spaces between tones come in 3 different sizes. But I also described another way, which is a bit less nice because the spaces between notes come in 4 different sizes. These 4 sizes are called semitones, but each has it own individual name.

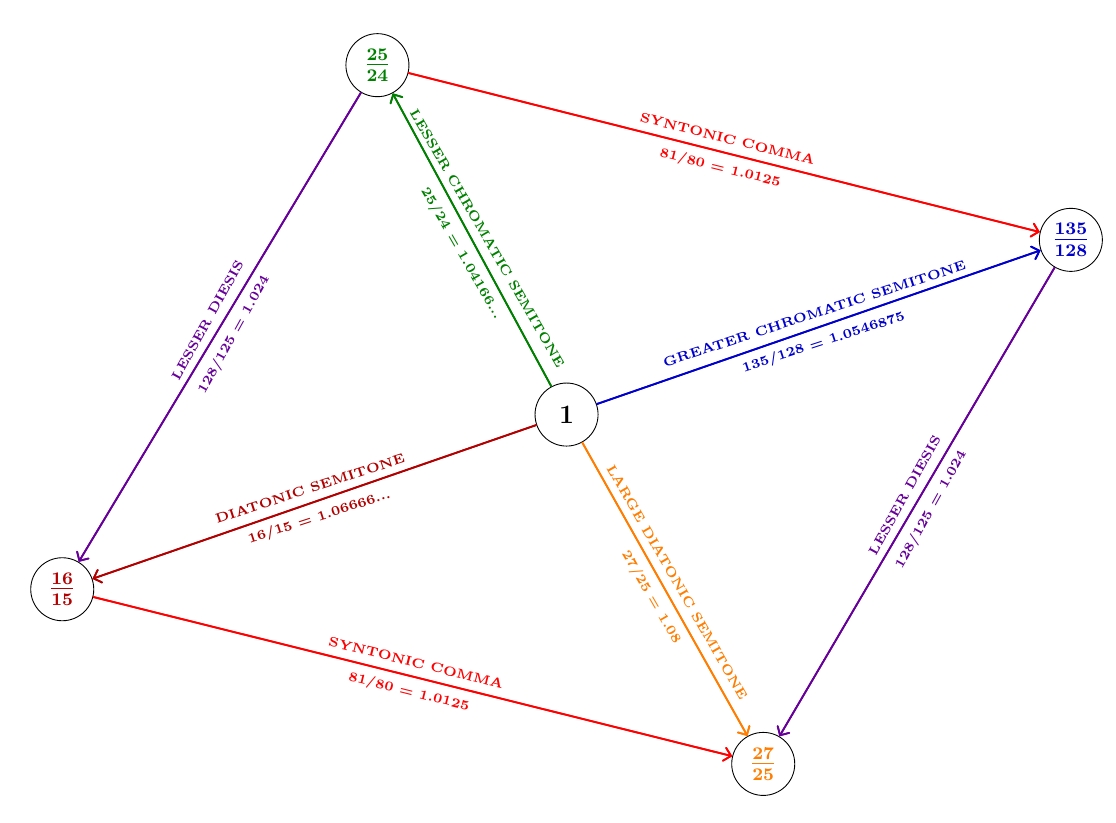

Now for something cool. Let's draw a parallelogram with these 4 semitones as corners. Let's draw arrows from those of lower frequency to those of higher frequency, and label these arrows by the frequency ratios:

Hey! The frequency ratios are just the same as in our other parallelogram!

What's going on?

Here's what: when we take the parallelogram of semitones and shift it up a perfect fourth, we get the parallelogram of tritones!

Let me spell that out more carefully. It turns out that each tritone in our first parallelogram is a semitone higher than the perfect fourth, 4/3. But there are 4 kinds of semitone, so we get 4 kinds of tritone: $$ \begin{array}{ccl} \displaystyle{ \frac{25}{24} \times \frac{4}{3}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{25}{18}} \\ \\ \displaystyle{ \frac{135}{128} \times \frac{4}{3}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{45}{32}} \\ \\ \displaystyle{ \frac{16}{15} \times \frac{4}{3}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{64}{45}} \\ \\ \displaystyle{ \frac{27}{25} \times \frac{4}{3}} &=& \displaystyle{\frac{36}{25}} \end{array} $$ So there's less going on than meets the eye: everything fits together.

We can also draw our parallelogram of semitones with the tonic, that is the frequency 1, in the middle:

The arrows here should make you think of vector addition, where adding two sides of a triangle can give you the third if the arrows are pointing the right way. But here the edges are just numbers, and we combine them by multiplying them. So each triangle in this picture gives an identity:

So you don't need to remember all these identities: they're all in the picture!

Our earlier picture describes the frequency ratios of the semitones at the opposite corners of this parallelogram:

So it gives two more identities:

But again, the picture relieves you of the need to remember the identities. And you don't need to learn all the fancy names for things if you don't want to!

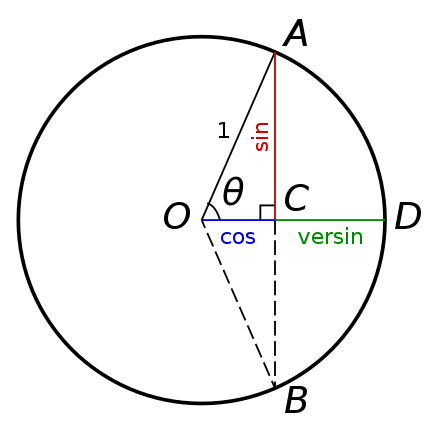

It's a bit like trigonometry. You can learn the names of lots of trig functions and identities relating them. Or you can just learn to understand the sine and cosine and the identities relating those. Or you can just learn to understand the function \(\exp(ix)\) and a couple of identities it obeys. The more you use trigonometry, or the more you enjoy it, the more it pays to remember. If you really love trigonometry and its history, learn about the versine:

Or go hog wild: learn about the haversine, the coversine, the vercosine, the covercosine, and more!

But if you don't want to learn this stuff, it's fine to take a more economical approach.

Puzzle 1. I drew the number 1 at the center of this parallelogram of semitones:

But what should really be at the center?

Puzzle 2. If we use the same logic, what should be at the center of this parallelogram of tritones?

Newton did his work on this in college when he was 22. This was 1665, the year he later fled Trinity College to avoid the Great Plague, went to the countryside, invented calculus, began thinking about gravity, and discovered that a prism can recombine colors of light to make white light.

Given this, I can't resist classifying all possible scales of this sort. Today we'll see that by a certain precise definition, there are 174,240 such scales! It will take a bit of combinatorics to work this out. Among this large collection of scales we will also find smaller sets of scales with nice properties. But I still don't know why those mathematicians chose the scales they did.

In studying this, and indeed in all my work on just intonation, I was greatly helped by this wonderful paper:

It's full of interesting diagrams:

Anyway, let's get going!

In Part 4, I examined the choices involved in building a just intonation scale. I described a general recipe for building such scales. These leads to 2 × 4 × 2 = 16 different scales, based on how you make the choices here:

| tonic | 1 | |

| minor 2nd | 16/15 | |

| major 2nd | 10/9 or 9/8 | |

| minor 3rd | 6/5 | |

| major 3rd | 5/4 | |

| perfect 4th | 4/3 | |

| tritone | 25/18 or 45/32 or 64/45 or 36/25 | |

| perfect 5th | 3/2 | |

| minor 6th | 8/5 | |

| major 6th | 5/3 | |

| minor 7th | 16/9 or 9/5 | |

| major 7th | 15/8 | |

| octave | 2 |

Newton's scale is one of these 16. Marin Mersenne had created the same scale in 1636, but Newton probably didn't know this. In fact I studied this scale in Part 4, where I claimed that it's the most popular just intonation scale of all! It's hard to be sure of that — but I certainly think it's the nicest one.

Here it is:

The intervals between the notes come in 3 different sizes, which we will discuss soon. In Part 4, I explained some reasons this scale is nice. For example, the intervals here are nearly palindromic! The first interval is the same as the last, and so on — except right at the middle of the scale, the 'tritone', where this symmetry is impossible because it would force \(\sqrt{2}\) to be a rational number.

In Part 4, I also considered another less popular scale among the 16 generated by my recipe:

In this one the intervals come in 4 different sizes! Let's make up abbreviations for them. In order of increasing size, they are:

With this notation, Newton's scale is

I'll say this scale has type (2,3,7,0) since it has 2 c's, 3 C's, 7 d's and 0 D's. The less popular scale I mentioned is

This scale has type (3,2,6,1). Arguably this scale is worse, because the large diatonic semitone is quite large compared to all the rest.

Muzzulini also describes some other just intonation scales. Here's one that Nicolas Mercator created around 1660 — not the Mercator with the map, the one who discovered the power series for the logarithm:

This is striking because it has two large diatonic semitones: it's of type (4,1,5,2).

Here's one that the music theorist William Holder wrote down in 1694:

This has three diatonic semitones — the most possible! It's of type (5,0,4,3).

Leonhard Euler came up with this scale in 1739:

This has type (3,2,6,1).

It would be interesting to find out, if possible, why various authors chose the scales they did. Did they scan the universe of possibilities and try to pick a scale that was optimal in some way — or did they did they just make one up? Answering this would require some historical investigation.

All these ruminations led me to some questions about enumerating and classifying scales, which I included as puzzles in Part 4. Now let me finally answer them!

Puzzle 1. As we've seen, the most popular 12-tone just intonation scale is of type (2,3,7,0). That is, it has 2 lesser chromatic semitones, 3 greater chromatic semitones, 7 diatonic semitones, and no large diatonic semitones. By permuting these semitones we can get many other scales. How many different scales can we get this way?

Answer. We have a 12-element set and we're asking: in how many ways can we partition it into a 2-element set, a 3-element set and a 7-element set? This is the kind of question that multinomial coefficients were designed to answer. The answer is

\[ \qquad \qquad \displaystyle{ \frac{12!}{2! \cdot 3! \cdot 7!} = 7920. } \qquad \qquad █ \]

Puzzle 2. Our second, less popular 12-tone just intonation scale is of type (3,2,6,1): it has 3 lesser chromatic semitones, 2 greater chromatic semitones, 6 diatonic semitones and 1 large diatonic semitone. How many other scales can we get by permuting these semitones?

Answer. By the same reasoning, we have

\[ \displaystyle{ \frac{12!}{3! \cdot 2! \cdot 6! \cdot 1!} = 55,440 } \]

such scales. █

These puzzles were warmups for a bigger question:

Puzzle 3. How many 12-tone scales are there where the spacing between each pair of successive notes is either a lesser chromatic semitone, a greater chromatic semitone, a diatonic semitone, or a large diatonic semitone?

Answer. The only types of scales allowed are quadruples \((i,j,k,\ell)\) of nonnegative integers where \[ \displaystyle{ \left(\frac{25}{24}\right)^i \left( \frac{135}{128} \right)^j \left( \frac{16}{15} \right)^k \left( \frac{27}{25} \right)^\ell = 2 }\]

or equivalently, \[ \displaystyle{ i \ln\left(\frac{25}{24}\right) + j \ln\left( \frac{135}{128} \right) + k \ln\left( \frac{16}{15} \right) + \ell \ln \left( \frac{27}{25} \right) = \ln 2. } \]

The four numbers \[ \ln\left(\frac{25}{24}\right), \ln\left( \frac{135}{128} \right),\ln\left( \frac{16}{15} \right), \ln \left( \frac{27}{25} \right) \]

span the 3-dimensional rational vector space with basis \(\ln 2, \ln 3, \ln 5,\) so they must obey one linear relation with integer coefficients (and others following from this one). This relation is \[ \displaystyle{ \ln\left(\frac{25}{24}\right) + \ln \left( \frac{27}{25} \right) = \ln\left( \frac{135}{128} \right) + \ln\left( \frac{16}{15} \right).} \]

This says cD = Cd: the lesser chromatic semitone followed by the large diatonic semitone takes you up to a frequency 9/8 higher, just like the greater chromatic semitone followed by the diatonic semitone.

This means that if a type \((i,j,k,\ell)\) is allowed, so is \((i+1,j-1,k-1,\ell+1)\) if \(j-1,k-1 \ge 0\). Furthermore, it means this move (and its inverse) can take you from any allowed type to all other allowed types.

So, let's start with the type where \(\ell,\) the number of large diatonic semitones, is as small as possible. This is our friend \[ (2,3,7,0). \]

We can get all other allowed types by repeatedly adding 1 to the first and last component of this vector and subtracting 1 from the other components. Thus, these are all the allowed types:

We can now use the methods of Puzzles 1 and 2 to count the scales of each type. We get:

\(\displaystyle{ \frac{12!}{2! \cdot 3! \cdot 7! \cdot 0!} } \) = 7,920 scales of type (2,3,7,0),

\(\displaystyle{ \frac{12!}{3! \cdot 2! \cdot 6! \cdot 1!} } \) = 55,440 scales of type (3,2,6,1),

\(\displaystyle{ \frac{12!}{4! \cdot 1! \cdot 5! \cdot 2!} } \) = 83,160 scales of type (4,1,5,2),

\(\displaystyle{ \frac{12!}{5! \cdot 0! \cdot 4! \cdot 3!} } \) = 27,720 scales of type (5,0,4,3).

So, we get a total of

This is a ridiculously large number of scales! But of course, not all are equally good. Let's impose some extra constraints.

The whole point of just intonation was to make the third equal to 5/4, and we also want to keep the fourth at 4/3 and the fifth at 3/2, as we had in Pythagorean tuning. When it comes to the second, either 10/9 or 9/8 are considered acceptable in just intonation. I like 9/8 a bit better, so let's do this:

Puzzle 4. How many 12-tone scales are there where the spacing between each pair of successive notes is either a lesser chromatic semitone, a greater chromatic semitone, a diatonic semitone, a large diatonic semitone, and:

Answer. With these constraints there are 1,600 allowed scales. The idea is this:

So, we get 4 × 2 × 1 × 4 × 500 = 1,600 scales of this sort. █