|

|

|

As you crack your eyes one morning your reason is assaulted by a strange sight. Over your head, humming quietly, there floats a monitor, an ethereal otherworldly screen on which is written a curious message. "I am the Screen of ultimate Truth. I am bulging with information and ask nothing better than to be allowed to impart it."

It would be nice if more math books started with something attention-grabbing like this. In fact, it appears near the beginning of

1) Geoffrey M. Dixon, Division Algebras: Octonions, Quaternions, Complex Numbers and the Algebraic Design of Physics, Springer Verlag, 1994.

Dixon is convinced that the details of the Standard Model of particle interactions can be understood better by taking certain mathematical structures very seriously. There are very few algebras over the reals where we can divide by nonzero elements: if we demand associativity and commutativity, just the reals themselves and the complex numbers. If we drop the demand for commutativity, we also get a 4-dimensional algebra called the quaternions, invented by Hamilton. If in addition we drop the demand for associativity, and ask only that our algebra be "alternative", we also get an 8-dimensional algebra called the octonions, or Cayley numbers. (I'll say what "alternative" means in "week61".) Clearly these are very special structures, and also clearly they play an important role in physics... or do they?

Well, few people doubt that the real numbers are fundamental to physics (though some advocates of the discrete might prefer the integers), and with emergence of quantum theory, if not sooner, the basic role of the complex numbers also became clear. Hamilton discovered the quaternions in the 1800s, and used them to formulate a beautiful theory of rotations in 3-dimensional space. They fell out of favor somewhat when the vectors of Gibbs proved simpler for many purposes, but their deeper importance became clear when people started studying spin: indeed, the Pauli matrices so important in physics are closely related to the quaternions, and it is the group of unit quaternions, SU(2), rather than the group of rotations in 3d space, SO(3), which turns out to be the symmetry group whose different representations correspond to particles of different spin. But what about the octonions?

Well, there are not too many places in physics yet where the octonions reach out and grab one with the force the reals, complexes, and quaternions do. But they are certainly out there, they have a certain beauty to them, and they are the natural stopping-point of a certain finite sequence of structures, so it is natural for people of a certain temperament to believe that they are there for a reason. Dixon makes a passionate case for this in the beginning of his book.

Suppose you were confronted with the Screen of Truth. What would you ask it? Dixon, being a physicist, naturally fantasizes asking it why the universe is the way it is! What kind of answer could this possibly have? Perhaps there is only one consistent way for things to be, and mathematics, with its unique and beautiful structures that are pure expressions of logical necessity, is trying to tell us something about this?

On the one hand this seems outrageous... especially to the hard-nosed pragmatist or empiricist in us. It seems old-fashioned, naive, and too good to be true. On the other hand, the universe is outrageous! It's outrageous that it exists in the first place, and doubly outrageous that it has the particular physical laws it does and no others. It has only been through the old-fashioned, naive belief that we can understand it using mathematics that we discovered what we have of its physical laws. So maybe eventually we will see that the basic structures of mathematics determine, in some mysterious sense, all the basic laws of physics. Or maybe we won't. In either case, there is a long way yet to go. As Dixon's Screen of Truth comments, before it departs:

Do you believe that were I to explain as much of what I know as you could comprehend that you would recognize it, that you would say, oh yes, this is but an extension of what we have already done, and though the mathematics is broader, the principles deeper, I am not surprised? Do you think you have asked even a fraction of the questions you need to ask?

Anyway, it is at least worth considering all the beautiful mathematical structures one runs into for their potential importance. For example, the octonions.

In order to write this week's Finds, I needed to learn a little about the octonions. I wanted some good descriptions of the octonions, that hopefully would "explain" them or at least make them easy to remember. So I asked for help on sci.physics.research, and I got some help from Greg Kuperberg, Ezra Getzler, Matthew Wiener, and Alexander Vlasov. After a while Geoffrey Dixon got wind of this and referred me to his work! I'll probably talk to him later this summer when I go back to Cambridge Massachusetts, and hopefully I'll learn more about octonions and the like.

But for now let me just give a quick beginner's introduction to the octonions. A lot of this appears in

2) William Fulton and Joe Harris, Representation Theory - a First Course, Springer Verlag, Berlin, 1991.

I should add that this book is a very good place to learn about Lie groups, Lie algebras, and their representations... I wish I had taken a course based on this book when I was in grad school!

Let's start with the real numbers. Then the complex number

a+bi

can be thought of as a pair

(a,b)

of real numbers. Addition is done component-wise, and multiplication goes like this:

(a,b)(c,d) = (ac - db,da + bc)

We can also define the conjugate of a complex number by

(a,b)* = (a,-b).

Now that we have the complex numbers, we can define the quaternions in a similar way. A quaternion can be thought of as a pair

(a,b)

of complex numbers. Addition is component-wise and multiplication goes like this

(a,b)(c,d) = (ac - d*b, da + bc*)

This is just like how we defined multiplication of complex numbers, but with a couple of conjugates (*'s) thrown in. To emphasize how similar the two multiplications are, we could have included the conjugates in the first formula, since the conjugate of a real number is just itself.

We can also define the conjugate of a quaternion by

(a,b)* = (a*,-b).

The game continues! Now we can define an octonion to be a pair of quaternions; as before, we add these component-wise and multiply them as follows:

(a,b)(c,d) = (ac - d*b, da + bc*).

One can also define the conjugate of an octonion by

(a,b)* = (a*,-b).

Why do the real numbers, complex numbers, quaternions and octonions have multiplicative inverses? I take it as obvious for the real numbers. For the complex numbers, you can check that

(a,b)* (a,b) = (a,b) (a,b)* = K (1,0)

where K is a real number called the "norm squared" of (a,b). The multiplicative identity for the complex numbers is (1,0). This means that the multiplicative inverse of (a,b) is (a,b)*/K. You can check that the same holds for the quaternions and octonions!

This game of getting new algebras from old is called the "Cayley-Dickson" construction. Of course, the fun we've had so far should make you want to keep playing this game and develop a 16-dimensional algebra, the "hexadecanions," consisting of pairs of octonions equipped with the same sor of multiplication law. What do you get? Why aren't there multiplicative inverses anymore? I haven't checked, because this is my summer vacation! I am learning about octonions just for fun, since I just finished writing some rather technical papers, and my idea of fun does not presently include multiplying two hexadecanions together to see why the norm-squared law (a,b) (a,b)* = (a,b)* (a,b) = K (1,0) breaks down. But I'm sure someone out there will enjoy doing this... and I'm sure someone else out there has already done it! So they should let me know what happens. There is something out there called "Pfister forms", which I think might be related.

[Toby Bartels did some nice work on hexadecanions in response to the above challenge, which appears at the end of this article.]

Now if we unravel the above definition of quaternions, by writing the quaternion (a+bi,c+di) as a+bi+cj+dk, we see that the multiplication law is

i2 = j2 = k2 = -1,

and

ij = -ji = k, jk = -kj = i, ki = -ik = j.

For more about the inner meaning of these rules, see "week5". Similarly, we can unravel the above definition of octonions by writing the octonion (a+bi+cj+dk,e+fi+gj+hk) as

a + b e1 + c e2 + d e3 + e e4 + f e5 + g e6 + h e7.

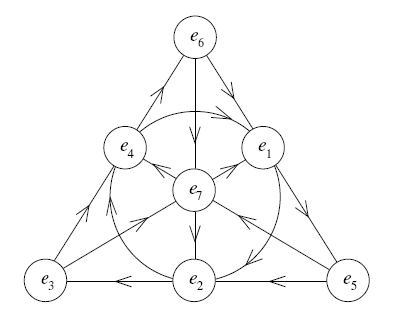

Note: since mathematicians are very impersonal, they usually call these seven dwarves e1,...,e7 instead of Sleepy, Grumpy, etc. as in the Disney movie. Any one of these 7 guys times himself is -1. Also, any two distinct ones anticommute; for example, e3 e7 = -e7 e3. There is a nice way to remember how to multiply them using the "Fano plane". This is a projective plane with 7 points, where by a "projective plane" I mean that any two points determine an abstract sort of "line", which in this case consists of just 3 points, and any two lines intersect in a point. It looks like this:

The "lines" are the 3 edges of the big triangle, the 3 lines going through a vertex, the center and the midpoint of the opposite edge, and the circle including e1, e2, and e3. All the "lines" are cyclically ordered, and that tells you how to multiply the seven dwarves. For example, the line that's actually a circle goes clockwise, so e1 e2 = e4, e2 e4 = e1, and e4 e1 = e2. The lines that are edges of the big triangle also point clockwise, so for example e5 e2 = e3, and cyclic permutations thereof, and e6 e3 = e4. The lines that go through the center point from the vertex to the midpoint of the opposite edge, so for example e3 e7 = e1. I hope that made sense; you can work it out yourself, of course.

My convention for numbering the seven dwarves in the picture above is completely arbitrary, so don't bother remembering it - make up your own if you prefer! The convention I chose looks sort of weird at first, but it has a couple of endearing features:

So those are the octonions in a nutshell. I should say a bit about how they relate to triality for SO(8), the exceptional Lie group G2, the group SU(3) which is so important in the study of the strong force, and to lattices like E8, Λ16 and the Leech lattice. But I will postpone that; for now you can consult Fulton and Harris, and also various papers by Dixon:

3) Geoffrey Dixon, Octonion X-product orbits, preprint available as hep-th/9410202.

Octonion X-product and E8 lattices, preprint available as hep-th/9411063.

Octonions: E8 lattice to Λ16, preprint available as hep-th/9501007.

Octonions: invariant representation of the Leech lattice, preprint available as hep-th/9504040.

Octonions: invariant Leech lattice exposed, preprint available as hep-th/9506080.

I am not presently in a position to assess these papers or Dixon's work relating division algebras and the Standard Model, but hopefully sometime I will be able to say a bit more.

Let me wrap up by saying a bit about the Leech lattice. As described in my review of Conway and Sloane's book ("week20"), there is a wonderful branch of mathematics that studies the densest ways of packing spheres in n dimensions. Most of the results so far concern lattice packings, packings in which the centers of the spheres form a subset of Rn closed under addition and scalar multiplication by integers. When n = 8, the densest known packing is given by the so-called E8 lattice. In "week20" I described how to get this lattice using the quaternions and the icosahedron. Briefly, it goes as follows. The group of rotational symmetries of the icosahedron (not counting reflections) is a subgroup of the rotation group SO(3) containing 60 elements. As mentioned above, SO(3) has as a double cover the group SU(2) of unit quaternions. So there is a 120-element subgroup of SU(2) consisting of elements that map to elements of SO(3) that are symmetries of the icosahedron. Now form all integer linear combinations of these 120 special elements of SU(2). We get a subring of the quaternions known as the "icosians''.

We can think of icosians as special quaternions, but we can also think of them as special vectors in R8, as follows. Every icosian is of the form

(a + √5 b) + (c + √5 d)i + (e + √5 f)j + (g + √5 h)k

with a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h rational - but not all rational values of a,...,h give icosians. The set of all vectors x = (a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h) in R8 that correspond to icosians in this way is the E8 lattice!

The Leech lattice is the densest known packing in 24 dimensions. It has all sorts of remarkable properties. Here is an easy way to get ones hands on it. First consider triples of icosians (x,y,z). Let L be the set of such triples with

x = y = z mod h

and

x + y + z = 0 mod h*

where h is the quaternion (-√5 + i + j + k)/2. Since we can think of an icosian as a vector in R8, we can think of L as a subset of R24. It is a lattice, and in fact, it's the Leech lattice! I have a bit more to say about the Leech lattice in "week20'', but the real place to go for information on this beast is Conway and Sloane's book. It turns out to be related to all sorts of other "exceptional'' algebraic structures. People have found uses for many of these in string theory, so if string theory is right, maybe they are important in physics. Personally, I want to understand them more deeply as pure mathematics before worrying too much about their applications to physics.

Here is what Toby Bartels wrote:

From: Toby Bartels Subject: Re: why hexadecanions have no inverses To: John Baez Date: Sun, 20 Aug 1995 I spent a couple days thinking about why hexadecanions have no inverses, and the first thing I want to say about it is that they do. However, these inverses are of limited applicability, because the hexadecanions are not a division algebra. A division algebra allows you to conclude, given x y = 0, that x or y is 0. If your algebra has inverses, you might try to multiply this equation by the inverse of x or y (whichever one isn't 0) to prove the other is 0, but this only works if the algebra is associative. Since the octonions and hexadecanions aren't associative, there's no reason (yet) to think either of these is a division algebra. It turns out that the octonions are a division algebra, despite not being associative, but the hexadecanions aren't. Why aren't the hexadecanions a division algebra? Because the real numbers aren't of characteristic 2. Allow me to explain. I will prove below that the 2^n onions are a division algebra only if the 2^(n-1) onions are associative. So, the question becomes: why aren't the octonions associative? Well, I've found a proof that 2^n onions are associative only if 2^(n-1) onions are commutative. So, why aren't the quaternions commutative? Again, I have a proof that 2^n onions are commutative only if 2^(n-1) onions equal their own conjugates. So, why don't the complex numbers equal their own conjugates? I have a proof that 2^n onions do equal their own conjugates, but it works only if the 2^(n-1) onions are of characteristic 2. The real numbers are not of characteristic 2, so the complex numbers don't equal their own conjugates, so the quaternions aren't commutative, so the octonions aren't associative, so the hexadecanions aren't a division algebra. I require a few identities about conjugates that hold for all 2^n onions: (x*)* = x, (x + y)* = x* + y*, and (x y)* = y* x*. (If these identities are reminiscent of identities for transposes of matrices, it is no coincidence.) I will prove these by induction. That is, if an identity holds for 2^(n-1) onions, I show it holds for 2^n onions. Since they hold trivially for the reals (n = 0), they hold for all. ((a, b)*)* = (a*, -b)* = ((a*)*, -(-b)). By the induction hypothesis and the nature of addition (an Abelian group), ((a*)*, -(-b)) = (a, b). ((a, b) + (c, d))* = (a + c, b + d)* = ((a + c)*, -(b + d)). By the induction hypothesis and addition again, ((a + c)*, -(b + d)) = (a* + c*, -b + -d) = (a*, -b) + (c*, -d) = (a, b)* + (c, d)*. The next proof needs the distribution of multiplication over addition. (a, b) ((c, d) + (e, f)) = (a, b) (c + e, d + f) = (a (c + e) - (d + f)* b, (d + f) a + b (c + e)*). By the induction hypothesis and the identity immediately above, (a (c + e) - (d + f)* b, (d + f) a + b (c + e)*) = (a c + a e - d* b - f* b, d a + f a + b c* + b e*) = (a c - d* b, d a + b c*) + (a e - f* b, f a + b e*) = (a, b) (c, d) + (a, b) (e, f). Also, ((a, b) + (c, d)) (e, f) = (a + c, b + d) (e, f) = ((a + c) e - f* (b + d), f (a + c) + (b + d) e*). By the induction hypothesis again, ((a + c) e - f* (b + d), f (a + c) + (b + d) e*) = (a e + c e - f* b - f* d, f a + f c + b e* + d e*) = (a e - f* b, f a + b e*) + (c e - f* d, f c + d e*) = (a, b) (e, f) + (c, d) (e, f). ((a, b) (c, d))* = (a c - d* b, d a + b c*)* = ((a c - d* b)*, -(d a + b c*)). Using the induction hypothesis and each of the above identities, ((a c - d* b)*, -(d a + b c*)) = (c* a* - (-b)* (-d), -d a + (-b) c*) = (c*, -d) (a*, -b) = (c, d)* (a, b)*. In light of the above identities, if I ever come across, say, (x y* + z)*, I'll simply write y x* + z* without a moment's hesitation. Since inductive proofs have been so useful, I'll use one to prove that 2^n onions always have inverses. First, I'll extend the method in John's article, beginning with an inductive proof that x x* = x* x is real. (a, b) (a, b)* = (a, b) (a*, -b) = (a a* + b* b, 0), and (a, b)* (a, b) = (a*, -b) (a, b) = (a* a + b* b, 0). The inductive hypothesis states that both a* a = a a* and b* b are real, so (a, b) (a, b)* = (a, b)* (a, b) is real. Since the sum of a positive real and a nonnegative real is positive, I can take this as a proof by induction that x x* = x* x is not only real, but is also positive unless x = 0 (which will be important). All you have to do now is check that these things are true of the 2^0 onions, and they are, quite trivially (since the 2^0 onions are the reals). Since the 2^n onions are always a vector space over the reals (as mentioned in John's article), x (x* / (x x*)) = (x x*) / (x x*) = 1. Since one can always divide by the real x x*, the inverse of x is x* / (x x*) in any 2^n onion algebra. To continue with the streak of inductive proofs, I will now try to prove that the 2^n onions are always a division algebra. (I will fail.) Assume 0 = (0, 0) = (a, b) (c, d) = (a c - d* b, d a + b c*). This gives the system of equations a c - d* b = 0 = d a + b c*. Multiplying, (a c) c* - (d* b) c* = 0 c* = 0 = d* 0 = d* (d a) + d* (b c*). If 2^(n-1) onions are associative, I can add the equations to get a (c c*) + (d* d) a = 0. Since c c* and d* d are real, they commute with a, and the division algebra nature of 2^(n-1) onions allows me to conclude that c c* + d* d = 0 (which implies c = d = 0 in light of positive definiteness) or that a = 0 (from which the original equation gives b = 0). Thus, the octonions are a division algebra (since the quaternions are associative), but the hexadecanions aren't (since the octonions aren't associative). (If you're reading carefully, you realize that I haven't really proved that the hexadecanions aren't a division algebra. I've failed to prove that they are, but that's not the same thing. When I first wrote this, I wasn't reading carefully; I will return to plug this hole later.) Thus, the 2^n onions are a division algebra iff the 2^(n-1) onions are a division algebra and are associative. So, let's try to prove associativity of 2^n onions by induction. ((a, b) (c, d)) (e, f) = (a c - d* b, d a + b c*) (e, f) = ((a c - d* b) e - f* (d a + b c*), f (a c - d* b) + (d a + b c*) e*) =((ac)e - (d* b)e - f* (da) - f* (b c*), f(ac) - f(d* b) + (da) e* + (b c*) e*). On the other hand, (a, b) ((c, d) (e, f)) = (a, b) (c e - f* d, f c + d e*) = (a (c e - f* d) - (f c + d e*)* b, (f c + d e*) a + b (c e - f* d)*) = (a(ce) - a(f* d) - (c* f*)b - (e d*)b, (fc)a + (d e*)a + b(e* c*) - b(d* f)). Assuming the induction hypothesis that 2^(n-1) onions are associative, these are equal in general iff 2^(n-1) onions also are commutative. Thus, 2^n onions are associative iff 2^(n-1) onions are associative and are commutative. So, let's try to prove commutativity of 2^n onions by induction. (a, b) (c, d) = (a c - d* b, d a + b c*). On the other hand, (c, d) (a, b) = (c a - b* d, b c + d a*). Assuming the induction hypothesis that 2^(n-1) onions are commutative, these are equal in general iff 2^(n-1) onions also equal their own conjugates. Thus, 2^n onions are commutative iff 2^(n-1) onions are commutative and equal their own conjugates. So, let's try to prove conjugate equality of 2^n onions by induction. (a, b) = (a, b). On the other hand, (a, b)* = (a*, -b). Assuming the induction hypothesis that 2^(n-1)onions equal their own conjugates, these are equal in general iff 2^(n-1) onions also have characteristic 2. (b = -b means 0 = b + b = 1 b + 1 b = (1 + 1) b = 2 b; this is true in general iff 0 = 2, which is what characteristic 2 means.) Thus, 2^n onions equal their own conjugates iff 2^(n-1) onions equal their own conjugates and have characteristic 2. Since the reals don't have characteristic 2, there's no point in trying to prove anything about that by induction. However, it's a general result that any algebra has characteristic 2 if it has a superalgebra of characteristic 2. Since the 2^n onions are all superalgebras of the reals (which means the reals are always isomorphic to a subset of the 2^n onions), none of the 2^n onions can have characteristic 2 if the reals don't. In summary, the definition of the reals as the complete ordered field, along with an initial definition that x* = x in the reals, allows trivial proofs that: they form a division algebra, they are associative, they are commutative, and they equal their own conjugates, but they don't have characteristic 2. (All of these, in fact, are true of any ordered field with this definition of conjugate, complete or not.) From this and the above considerations, the complex numbers form a division algebra, are associative, and are commutative, but they neither equal their own conjugates nor have characteristic 2. From this, the quaternions form a division algebra and are associative, but they neither are commutative, equal their own conjugates, nor have characteristic 2. From this, the octonions form a division algebra but they neither associative, are commutative, equal their own conjugates, nor have characteristic 2. Finally, the hexadecanions neither form a division algebra, are associative, are commutative, equal their own conjugates, nor have characteristic 2. At this point, I must return to the logical hole I mentioned earlier. But I want to work with a different algebraic concept than a division algebra; instead I will use (inspired by Doug Merrit's post to sci.physics.research) what I guess is called `alternativity', which says x (x y) = (x x) y. I don't like putting alternativity into the pattern, since associativity implies alternativity. All the other properties (commutativity, conjugate equality, characteristic) are logically independent in general. I'd like to prove that every associative 2^n onion algebra is alternative, just as I proved every commutative one was associative, without its having been obvious to begin with. Well, I will be disappointed even more badly later on. Taking the conjugate of x (x y) = (x x) y, (y* x*) x* = y* (x* x*), so left alternativity implies right alternativity, for 2^n onions. I require an additional general identity of 2^n onions. Earlier, I proved by induction that x x* was real, but now I need the reality of x + x*. Like everything else, this is proved by induction. (a, b) + (a, b)* = (a, b) + (a*, -b) = (a + a*, 0). Thus, if a + a* is real, (a, b) + (a, b)* is real. Since x + x* is real when x is real, x + x* is real when x is any 2^n onion. Now suppose we're working in an alternative 2^n onion algebra. x (x y) + x* (x y) = (x + x*) (x y). Since x + x* is real, it associates, so x (x y) + x* (x y) = ((x + x*) x) y = (x x) y + (x* x) y. Since x (x y) = (x x) y, x* (x y) = (x* x) y, which will be needed. Let's attempt to prove by induction that 2^n onions are always alternative. (a, b) ((a, b) (c, d)) = (a, b) (a c - d* b, d a + b c*) = (a (a c - d* b) - (d a + b c*)* b, (d a + b c*) a + b (a c - d* b)*) = (a(ac) - a(d* b) - (a* d*)b - (c b*)b, (da)a + (b c*)a + b(c* a*) - b(b* d)). Meanwhile, ((a, b) (a, b)) (c, d) = (a a - b* b, b a + b a*) (c, d) =((aa)c - (b* b)c - d* (ba) - d* (b a*), d(aa) - d(b* b) + (ba) c* + (b a*) c*). These are indeed equal in general iff 2^(n-1) onions are associative. The last sentence may not be immediately obvious. The induction hypothesis and its corollaries leave us with x (y z) + (x* y) z = y (z x) + y (z x*) as a necessary and sufficient condition. It may not be clear that associativity implies this, much less vice versa. However, the reality of x + x* once more enters the picture. y (z x) + y (z x*) = y (z (x + x*)) = (x + x*) (y z) = x (y z) + x* (y z). Thus, the condition becomes x (y z) + (x* y) z = x (y z) + x* (y z), which is equivalent, in the general case, to associativity. To sum up the findings so far: For any n, the 2^n onions form a vector space over the reals. x + x* and x x* are real if x is any 2^n onion; additionally, x x* = x* x. Every 2^n onion has an inverse, which is a real multiple of its conjugate. Conjugation is analogous to matrix transposition in that (x*)* = x, (x + y)* = x* + y*, and (x y)* = y* x*. Multiplication distributes over addition every time. For no n do all 2^n onions equal their own negatives. 2^(n+1) onions equal their own conjugates iff 2^n onions equal their own conjugates and their own negatives. all 2^(n+1) onions commute iff all 2^n onions commute and equal their own conjugates. 2^(n+1) onions are associative iff 2^n onions are associative and commutative. 2^(n+1) onions are alternative iff 2^n onions are alternative and associative. The 2^n onions form a division algebra if they are alternative. I will be satisfied if I can prove the converse of the last statement. In light of the results about alternativity, my original attempt to prove that division of 2^n onions requires associativity of 2^(n-1) onions looks even more convincing, (since alternativity of 2^(n-1) onions can be included in the induction hypothesis), but it's still not valid. I still haven't shown that, if 2^(n-1) onions aren't alternative, there must be non0 2^n onions x and y such that x y = 0. There doesn't seem to be any reason why there shouldn't be, but there just might happen not to be any. So, despite the inelegance of it all, in order to prove that the hexadecanions aren't a division algebra, I'm forced to exhibit non0 x and y such that x y = 0. Just playing around, I found (e_1, e_4) (-1, e_5) = (e_1 (-1) - (e_5)* e_4, e_5 e_1 + e_4 (-1)*) = (-e_1 + e_5 e_4, e_5 e_1 - e_4). Since e_5 e_4 = (0, i) (0, 1) = (i, 0) = e_1 and e_5 e_1 = (0, i) (i, 0) = (0, i* i) = (0, 1) = e_4, (e_1, e_4) (-1, e_5) = (0, 0) = 0. The 2^n onions can't be a division algebra if the 2^(n-1) onions aren't. If x y = 0 in the 2^(n-1) onions, (x, 0) (y, 0) = (x y, 0) = (0, 0) = 0. Thus, the octonions and below are the only 2^n onions to be division algebras. Still, I wish I had a proof of this that didn't require the ugly brute force use of a specific counterexample. (This is the interested reader's cue ...) -- Toby

By the way, in a post to sci.physics.research on November 2, 1999, Ralph Hartley pointed out that even if we start with a field of characteristic 2, repeatedly applying the Cayley-Dickson construction will not lead to an infinite sequence of division algebras, because it's not true in this case that if x is nonzero, xx* is nonzero. The problem is that a field of characteristic 2 can't be an ordered field.

© 1995 John Baez

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu

|

|

|