How can we detect and understand oncoming crises in time to avert them? Sometimes we must "zoom out": expand our perspective and find similar situations in the distant past. A good example is climate change. What can a few degrees of warming do? To answer this, we need to know some history: how the Earth's climate has changed over the last 65 million years.Click here to see the slides of this talk:

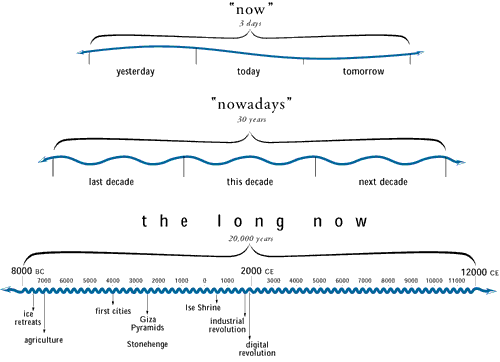

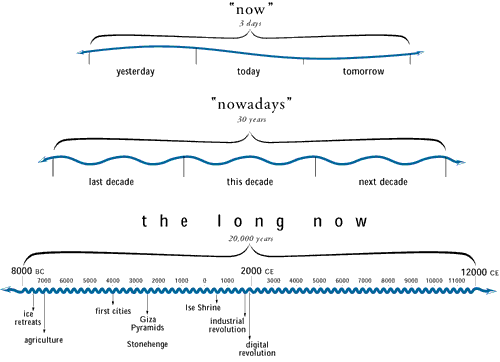

The Long Now Foundation

was established in 01996 to develop

the Clock and Library

projects, as well as to become the seed of a very long term cultural

institution. They hope to provide counterpoint to today's "faster/cheaper"

mind set and promote "slower/better" thinking. They hope to creatively

foster responsibility in the framework of the next 10,000 years.

Here's Stewart Brand's summary of the talk:

The graphs we see these days, John Baez began, all look vertical — carbon burning shooting up, CO2 in the air shooting up, global temperature shooting up, and population still shooting up. How can we understand what really going on? "It's like trying to understand geology while you're hanging by your fingernails on a cliff, scared to death. You think all geology is vertical."So, zoom out for some perspective. An Earth temperature graph for the last 18,000 years shows that we've built a false sense of security from 10,000 years of unusually stable climate. Even so, a "little dent" in the graph of a drop of only 1 degree Celsius put Europe in a what's called "the little ice age" from 1555 to 1850. It ended just when industrial activity took off, which raises the question whether it was us that ended it.

He who cannot draw on 3,000 years is living hand to mouth. - Goethe

© 2006 John Baez - except for images (the above image was

produced by The

Long Now Foundation)

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu