We're getting married on the 17th of this month. In a way it's no big deal, since we'll have been together 20 years this April — and we'll have the big party not on our wedding but on April 1st, our official anniversary. Anyone can have a wedding; 20th anniversaries are worth a bit more.

But, getting married is turning out to be a pleasant opportunity for doing fun silly things together, especially since we're avoiding most of the stressful hoopla. For example, shopping for rings has awakened my long-neglected alchemical fondness for rare elements. If it weren't so decadent, I would have gotten a ring made of platinum! It's delightfully dense, produced only by supernovae:

Today, White House officials began some serious backpedaling. They put out a letter saying that "Beginning in June 2001, President Bush has consistently acknowledged climate change is occurring and humans are contributing to the problem." They also claimed that "Climate change has been a top priority since the president's first year in office."

A week ago, White House spokesman Tony Snow said, "Perhaps folks have not taken notice of the fact that this is an administration that's been keenly committed both to environmentalism and conservationism from the start." He added: "The long national slumber may be approaching an end."

Hilarious — but good news in its own way. We can't expect any real action on the environment from the Bush administration. They'll continue to drag their heels as best they can. But at least they've realized it's hopeless to publicly deny the reality of human-induced climate change. Now the best excuse for inaction is claiming that the situation is hopeless.

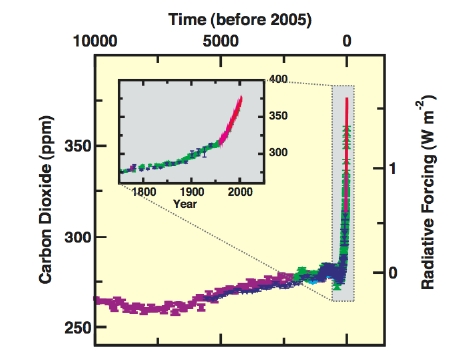

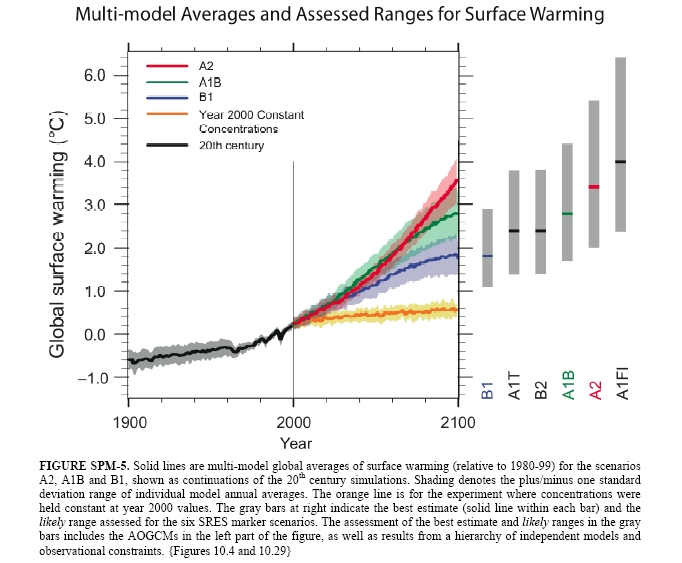

Perhaps this report was the nail in the "climate skeptics'" coffin:

Here's the problem in a nutshell:

The consequences? See these temperature projections for the years to come. The lowest one is where, due to some miracle, CO2 emissions are held constant starting now:

I spent a while thinking about how I really didn't want to be doing

this... mainly because all this work was our attempt to recover

from a hot summer with a broken sprinkler system and an inattentive house

guest, followed by a frosty cold snap in January that killed a lot of

the lantana and morning glory.

Planting a garden is an act of optimism.

Clearing away plants that have died from drought or frost is a lesson

in the mortality of all things.

After a while I got happy: with four of us working away,

things were improving noticeably. I started thinking about

the look of a well-run, active household - or even better, a farmhouse.

It's not perfectly neat and clean. Stuff may be strewn around. But it's

there for a purpose - it doesn't lie around forever, gathering dust.

The house hums with interconnected webs of activity. It's like an

ecosystem. There are patches that get neglected for a while... but

eventually a spring cleaning comes along and whips them into shape.

My mother is a perfectionist who likes the house to be as clean as a

museum. As I kid I rebelled against this "esthetic

totalitarianism", but I had trouble envisioning the

alternatives - all that came to mind were sloppiness and minimalism,

and I chose the latter. It took me a while to discover the robust

charm of an active house.

is that it's not!

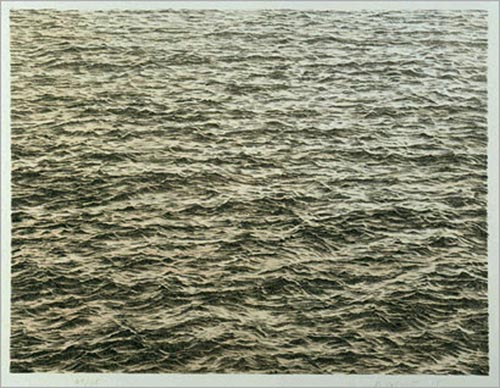

It's a drawing by Vija Celmins. She does amazing work.

She's having a retrospective

at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles from January 28th until April 22nd,

and I hope I have the time to go see it.

February 10, 2007

We spend the day cleaning up the yard, planting herbs (lavender,

savory, purple sage, thyme), flowers (California poppies and wildflowers)

and ground cover (creeping thyme) while a fellow worked on our broken sprinkler

system, and his assistant cleared out dried leaves and accumulated brush.

February 11, 2007

The cool thing about this photo:

February 12, 2007

I've been made a member

of the Foundational Questions

Institute. This is an organization that seeks:

To catalyze, support, and disseminate research on questions at the foundations of physics and cosmology, particularly new frontiers and innovative ideas integral to a deep understanding of reality but unlikely to be supported by conventional funding sources.Since I think fundamental physics is stuck, this seems like a good thing to me.

Vernor Vinge is talking at the Long Now Foundation on Thursday February 15th. Stewart Brand writes:

Science fiction writer Vernor Vinge invented the concept that dominates thinking about technology these days. He called it "the Singularity" — the idea that technology (computer tech, biotech, nanotech) is now accelerating so exponentially that it will lead to a massive, irreversible, and profoundly unpredictable transformation of humanity by mid-century.This Thursday evening Vinge will challenge his own idea for the first time: "I have some plausible, non-singularity scenarios that get us into a human-scale world with long time horizons. I'll describe the near-term peculiarities I see for such scenarios and then discuss what such a world might be like across ten or twenty thousand years. Finally, I'd like to talk about dangers and defenses related to these scenarios."

Here's Stewart Brand's summary:

Vinge began by declaring that he still believes that a Singularity event in the next few decades is the most likely outcome — meaning that self-accelerating technologies will speed up to the point of so profound a transformation that the other side of it is unknowable. And this transformation will be driven by Artifical Intelligences (AIs) that, once they become self-educating and self-empowering, soar beyond human capacity with shocking suddeness.He added that he is not convinced by the fears of some that the AIs would exterminate humanity. He thinks they would be wise enough to keep us around as a fallback and backup — intelligences that can actually function without massive connectivity! (Later in the Q&A I asked him about the dangerous period when AI's are smart enough to exterminate us but not yet wise enough to keep us around. How long would that period be? "About four hours," said Vinge.)

Since a Singularity makes long-term thinking impractical, Vinge was faced with the problem of how to say anything useful in a Seminar About Long-term Thinking, so he came up with a plausible set of scenarios that would be Singularity-free. He noted that they all require that we achieve no faster-than-light space travel.

The overall non-Singularity condition he called "The Age of Failed Dreams." The main driver is that software simply continues failing to keep pace with hardware improvements. One after another, enormous billion-dollar software projects simply do not run, as has already happened at the FBI, air traffic control, IRS, and many others. Some large automation projects fail catastrophically, with planes running into each. So hardware development eventually lags, and materials research lags, and no strong AI develops.

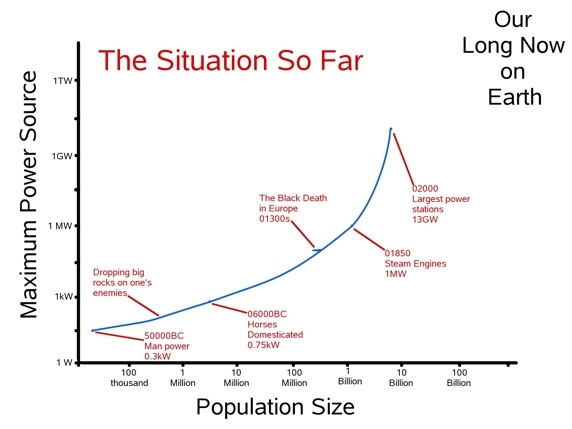

To differentiate visually his three sub-scenarios, Vinge showed a graph ranging over the last 50,000 and next 50,000 years, with power (in maximum discrete sources) plotted against human population, on a log-log scale. Thus the curve begins at the lower left with human power of 0.3 kilowatts and under a hundred thousand population, curves up through steam engines with one megawatt of power and a billion population, up further to present plants generating 13 gigawatts.

His first scenario was a bleak one called "A Return to MADness." Driven by increasing environmental stress (that a Singularity might have cured), nations return to nuclear confrontation and policies of "Mutually Assured Destruction." One "bad afternoon," it all plays out, humanity blasts itself back to the Stone Age and then gradually dwindles to extinction.

His next scenario was a best-case alternative named "The Golden Age," where population stabilizes around 3 billion, and there is a peaceful ascent into "the long, good time." Humanity catches on that the magic ingredient is education, and engages the full plasticity of the human psyche, empowered by hope, information, and communication. A widespread enlightened populism predominates, with the kind of tolerance and wise self-interest we see embodied already in Wikipedia.

One policy imperative of this scenario would be a demand for research on "prolongevity" — "Young old people are good for the future of humanity." Far from deadening progress, long-lived youthful old people would have a personal stake in the future reaching out for centuries, and would have personal perspective reaching back for centuries.

The final scenario, which Vinge thought the most probable, he called "The Wheel of Time." Catastrophes and recoveries of various amplitudes follow one another. Enduring heroes would be archaeologists and "software dumpster divers" who could recover lost tools and techniques.

What should we do about the vulnerabilities in these non-Singularity scenarios? Vinge's main concern is that we are running only one, perilously narrow experiment on Earth. "The best hope for long-term survival is self-sufficient off-Earth settlements." We need a real space program focussed on bringing down the cost of getting mass into space, instead of "the gold-plated sham" of present-day NASA.

There is a common critique that there is no suitable place for humans elsewhere in the Solar System, and the stars are too far. "In the long now," Vinge observed, "the stars are not too far."

Stewart Brand

For lots of people, getting married feels more like this:

In case you're wondering, the fool in this movie is using a wingsuit.

On a wholly different note, here's an interesting free book on sustainable development:

In a small ceremony in our back yard, our friend the anthropologist Al Fix served as solemnizer, as shown here. Also attending were his wife Betsy, my aunt Marilyn Goudzwaard, and our friend Lothar von Falkenhausen. Our other relatives were unable to attend. But that's okay: the big party will take place later this year, on our 20th anniversary of being together — April Fool's Day!

After the ceremony we had dinner at the Mission Inn Restaurant.

February 18, 2007

Today we're having our big annual party celebrating the Lunar New Year.

According to the Chinese lunisolar calendar, it's the end of the Year of the Dog, and the start of the Year of the Pig. The lunar calendar inevitably drifts away from the solar one, because there are 12.368 lunar months per year. So, occasionally they need to stick in an extra "intercalary month". That caused this Year of the Dog to officially have "two springs" &mdash so it was especially auspicious for marriage!

That's why we got married yesterday: we wanted to do it before the Year of the Dog ended.

(Don't worry; I don't actually believe in this stuff. But, they say it works even if you don't believe in it.)

With the help of a bevy of Chinese grad students, we're making several hundred jiaozi — the traditional Chinese New Year's dumplings:

For their theses, Derek and Jeff are both working on a problem that's exercised me for years: seeing BF theory as an extended topological field theory in all dimensions, and understanding its relation to quantum gravity. Derek got pulled in the direction of geometry; Jeff got pulled in the direction of n-categories, so a casual observer might not even notice that they're working on the same subject. But they are! And, I hope this becomes clearer in their future work. They may wind up doing other things. Derek will probably be talking with Greg Kuperberg about quantum topology and Steve Carlip about quantum gravity, while Jeff will be talking to Dan Christensen about quantum gravity and categories, and also visiting the Perimeter Institute. All this could be just what they need to dig deeper into the topics touched on by their theses... or they could move in other directions.

Another student is leaving me as well: Mike Stay. He hasn't even finished his qualifiers yet, but he's already been doing excellent work on category-theoretic logic and quantum computation. Unfortunately, he has a family to support, and they're going broke on the salary we give our grad students. Since he understands cryptography and computer security issues, he was able to get himself a job at Google with an eye-poppingly large salary. He may continue working with me from afar.

All this will slash the number of my grad students here at UCR from 5 to 2. Right now this seems like a good thing: I'm feeling overworked, tired and burnt out. It's not just because I have lots of students: this quarter I'm the graduate recruitment advisor and serving on some hiring committees. I'm teaching classes on quantization, computation, and algebraic topology. I just got married! I just threw a huge party. Every week I discuss math with James Dolan, Alissa Crans and Danny Stevenson. I'm blogging heavily. And, I'm trying — with little success — to finish up 3 big papers. No, 4.

All these things are individually lots of fun. But, I need more time

to do... nothing in particular.

February 22, 2007

Lisa's left yesterday (Wednesday) to give a talk at Penn State, and

she's coming back on Sunday. So, I have a bit more spare time. Last

night I had fun listening to some of the nasty music Lisa doesn't like

&mdash like this album:

The story goes on to explain that Cahill and others are protesting the arrival of real-world corporations in Second Life. Companies are starting to do this because it makes them look cool. Linden Lab likes it, because big companies have the money it takes to help keep the game going. According to Peter Ludlow, editor of Crypto Anarchy, Cyberstates, and Pirate Utopias, chain stores such as American Apparel are being dropped into "this fantasy world with unicorns and flying elephants. It's an eyesore." Some disgruntled residents are moving on to new sites, such as Multiverse. And so it goes...Virtual Loses its Virtues

By Alana Semuels, Los Angeles Times Staff Writer

February 22, 2007

Like any pioneer, Marshal Cahill arrived in a new world curious and eager to sample its diversions. Over time, though, he saw an elite few grabbing more than their share.

They bought up all the plum real estate. They awarded building contracts to friends. They stifled free speech.

Cahill saw a bleak future, but he felt powerless to stop them. So he detonated an atomic bomb outside an American Apparel outlet. Then another outside a Reebok store.

As political officer for the Second Life Liberation Army, Cahill is passionately committed to righting what he considers the wrongs of a world that exists only on the computer servers of Linden Lab in San Francisco.

Linden is the company behind Second Life, a virtual world in which Internet users act out parallel fantasy lives. They date. They build houses. They work. Some players support themselves in real life by selling goods or services in the game.

Some see the space as a utopia free of real-world constraints, where they can build their vision of a perfect realm from scratch. It's a place where denizens can reinvent themselves as a supermodel or a rodent, own an island or fly, no plane necessary, to a virtual Grauman's Chinese Theatre.

In the last year, the number of people who had visited Second Life skyrocketed from 100,000 to 2 million. As the population grows, early denizens are learning the truth of Jean-Paul Sartre's observation "Hell is other people."

The website is facing the problem that many would-be utopias faced before it: When building the ideal world, it's impossible to change while remaining perfect in everyone's eyes.

Cahill and his compatriots say they don't necessarily mind the new residents, but they want more influence in deciding the future of the virtual world. Most important, they want Linden Lab to allow voting on issues affecting their in-world experience.

"The population of the world should have a say in the running of the world," Cahill said during an in-world interview. Cahill is this participant's online name, incidentally. He refused to reveal his real-world name for fear of banishment from Second Life.

The army has staged a number of protests in Second Life to publicize its position. Three gun-toting members shot customers outside American Apparel — bullet wounds in Second Life are not fatal but merely disrupt a user's experience &mdash and Reebok stores last year.

Then they stepped up the campaign, exploding nukes, which manifested themselves in swirling fireballs that thrust users at the scene into motionless limbo.

Cahill said the group targeted in-world corporate locations to draw real-world attention to its cause.

Long-term Second Life residents have given Cahill and his conspirators money to buy virtual guns and other weapons. Cahill says he believes that 80% of long-term residents support his cause.

Cahill, an entrepreneur who splits his time between London and San Francisco in the real world, compares himself to John Adams, the second U.S. president. Adams would have been considered a terrorist by his foes, Cahill said, because he helped lead the American Revolution. The Second Life Liberation Army, he said, is just trying to make the world a better place.

[....]

For more try these:

Of course I'm at UC Riverside, not UC Irvine. Someone had crossed out this address and written:

She had no idea who did this, or why. Did some postal worker, or some mathematican at Irvine, know I'd given a talk at Dartmouth? That's the only explanation I can dream up!

She said the package was a CD from one "Celeste de Vine", and that she'd forward it to me.

Anyway, I got the package a while ago. It contains a letter:

Dear John,A touching note! Now I will look at the book.Please find enclosed a novel, "Mr. Grumles' Dream", that is about a 14 year old girl who is learning to overcome her dyslexia by writing a book about a Theory of Everything. Her mentor in the story, a man who has a keen interest in the Nature of Reality, is also dyslexic, as indeed, is the author. The work is an attempt to give a rather black comic insight into the dyslexic mind for those who do not suffer from this affliction, and, how this disabling condition with all of its negative social and psychological consequences can be overcome.

As it is a work of fiction and proceeds from the book will be going to the charity Dyslexia Action, I hope you enjoy the use that I have made of the Feature, "Out of the Void", that you were named in, for the journal, New Scientist. You will be in good company, as even a cursory glance at the list of the Venerable contributors will soon reveal.

With 1 in 5 children suffering from "learning difficulties" - a term already heavily laden with negative connotations - and a large % of those dyslexic, it is a global problem with enormous social consequences that needs to be addressed right now.

I'd like to think that my book may go some way in redressing these problems by providing a very positive take on the condition, while at the same time, provide more than just hope for the dyslexic. It has taken me over 3 hours to write this letter but I would like to think that it is coherent and - convincing. Ditto the book, if in a somewhat more humorous vein.

Yours,

Celeste de Vine

Hmm, it's interesting...

February 26, 2007

Education is incredibly important: it's how the human race leverages

itself forward. This idea is widely accepted, though often in a degraded

form which focuses solely on the economic benefits of a

well-trained "labor pool". But that's another matter —

right now I want to rant about something else: given the importance of

education, how little we know about how it works!

For example, we're just realizing how much praise of the wrong sort can hurt children:

For a few decades, it's been noted that a large percentage of all gifted students (those who score in the top 10 percent on aptitude tests) severely underestimate their own abilities. Those afflicted with this lack of perceived competence adopt lower standards for success and expect less of themselves. They underrate the importance of effort, and they overrate how much help they need from a parent.There's a lot more in this interesting article.When parents praise their children's intelligence, they believe they are providing the solution to this problem. According to a survey conducted by Columbia University, 85 percent of American parents think it's important to tell their kids that they're smart. In and around the New York area, according to my own (admittedly nonscientific) poll, the number is more like 100 percent. Everyone does it, habitually. The constant praise is meant to be an angel on the shoulder, ensuring that children do not sell their talents short.

But a growing body of research — and a new study from the trenches of the New York public-school system — strongly suggests it might be the other way around. Giving kids the label of "smart" does not prevent them from underperforming. It might actually be causing it.

For the past ten years, psychologist Carol Dweck and her team at Columbia (she's now at Stanford) studied the effect of praise on students in a dozen New York schools. Her seminal work — a series of experiments on 400 fifth-graders — paints the picture most clearly.

Dweck sent four female research assistants into New York fifth-grade classrooms. The researchers would take a single child out of the classroom for a nonverbal IQ test consisting of a series of puzzles — puzzles easy enough that all the children would do fairly well. Once the child finished the test, the researchers told each student his score, then gave him a single line of praise. Randomly divided into groups, some were praised for their intelligence. They were told, "You must be smart at this." Other students were praised for their effort: "You must have worked really hard."

Why just a single line of praise? "We wanted to see how sensitive children were," Dweck explained. "We had a hunch that one line might be enough to see an effect."

Then the students were given a choice of test for the second round. One choice was a test that would be more difficult than the first, but the researchers told the kids that they'd learn a lot from attempting the puzzles. The other choice, Dweck's team explained, was an easy test, just like the first. Of those praised for their effort, 90 percent chose the harder set of puzzles. Of those praised for their intelligence, a majority chose the easy test. The "smart" kids took the cop-out.

Why did this happen? "When we praise children for their intelligence," Dweck wrote in her study summary, "we tell them that this is the name of the game: Look smart, don't risk making mistakes." And that's what the fifth-graders had done: They'd chosen to look smart and avoid the risk of being embarrassed.

In a subsequent round, none of the fifth-graders had a choice. The test was difficult, designed for kids two years ahead of their grade level. Predictably, everyone failed. But again, the two groups of children, divided at random at the study's start, responded differently. Those praised for their effort on the first test assumed they simply hadn't focused hard enough on this test. "They got very involved, willing to try every solution to the puzzles," Dweck recalled. "Many of them remarked, unprovoked, 'This is my favorite test'" Not so for those praised for their smarts. They assumed their failure was evidence that they weren't really smart at all. "Just watching them, you could see the strain. They were sweating and miserable".

Having artificially induced a round of failure, Dweck's researchers then gave all the fifth-graders a final round of tests that were engineered to be as easy as the first round. Those who had been praised for their effort significantly improved on their first score — by about 30 percent. Those who'd been told they were smart did worse than they had at the very beginning — by about 20 percent.

And here's another fascinating thing Dweck seems to have discovered: teaching children how the brain develops new neurons when you learn stuff can help them learn!

A new study in the scientific journal Child Development shows that if you teach students that their intelligence can grow and increase, they do better in school.It makes me a little nervous reading two amazing discoveries in education by the same person in the course of a week. I hope these findings are confirmed — or disconfirmed! But either way, I wish someday we'd get serious about learning how to teach people. We could start a virtuous circle of rapid cultural development. The results could be amazing!All children develop a belief about their own intelligence, according to research psychologist Carol Dweck from Stanford University.

"Some students start thinking of their intelligence as something fixed, as carved in stone," Dweck says. "They worry about, 'Do I have enough? Don't I have enough?'"

Dweck calls this a "fixed mindset" of intelligence.

"Other children think intelligence is something you can develop your whole life," she says. "You can learn. You can stretch. You can keep mastering new things."

She calls this a "growth mindset" of intelligence.

Dweck wondered whether a child's belief about intelligence has anything to do with academic success. So, first, she looked at several hundred students going into seventh grade, and assessed which students believed their intelligence was unchangeable, and which children believed their intelligence could grow. Then she looked at their math grades over the next two years.

"We saw among those with the growth mindset steadily increasing math grades over the two years," she says. But that wasn't the case for those with the so-called "fixed mindset." They showed a decrease in their math grades.

This led Dweck and her colleague, Lisa Blackwell, from Columbia University to ask another question.

"If we gave students a growth mindset, if we taught them how to think about their intelligence, would that benefit their grades?" Dweck wondered.

So, about 100 seventh graders, all doing poorly in math, were randomly assigned to workshops on good study skills. One workshop gave lessons on how to study well. The other taught about the expanding nature of intelligence and the brain.

The students in the latter group "learned that the brain actually forms new connections every time you learn something new, and that over time, this makes you smarter."

Basically, the students were given a mini-neuroscience course on how the brain works. By the end of the semester, the group of kids who had been taught that the brain can grow smarter, had significantly better math grades than the other group.

"When they studied, they thought about those neurons forming new connections," Dweck says. "When they worked hard in school, they actually visualized how their brain was growing."

Dweck says this new mindset changed the kids' attitude toward learning and their willingness to put forth effort. Duke University psychologist, Steven Asher, agrees. Teaching children that they're in charge of their own intellectual growth motivates a child to work hard, he says.

"If you think about a child who's coping with an especially challenging task, I don't think there's anything better in the world than that child hearing from a parent or from a teacher the words, 'You'll get there.' And that, I think, is the spirit of what this is about."

Dweck's latest book, Mindset: The New Psychology of Success, gives parents and teachers specific ways to teach the growth mindset of intelligence to children.

Right now the United States seems to be heading the other direction:

Hi,In reply to my February 16th entry, my friend Garrett Lisi writes:Just reading your diary - interesting stuff about educating kids. I found the first part less interesting than the second - the first being, in my view, really obvious, but the second (teaching them neuroscience) being absolutely fantastic.

There's some sort of converse to the first part (telling children they're intelligent makes them do worse; telling them they tried really hard makes them do better) that I haven't quite figured out, but it's something to do with the fact that I was really bad at sport at school, and my teachers always accused me of not trying hard enough. The thing is I was already trying exceedingly hard - I was just fundamentally bad at sport, and they couldn't believe any human being could be trying hard and still be so bad. The result was that I eventually gave up trying at all, became sulky and argumentative, and pretended to be ill during sports lessons as much as possible. It seems related somehow...

Q: What's crazier than a wingsuit?

To a desert dweller, anyone who complains of rain sounds like a spoiled brat, unless they're actually suffering floods.

Speaking of desert dwellers, here's a book I'd like to read:

What happened to the great civilizations of the Southwest that flowered so exquisitely and flickered out so abruptly? In addition to the Anasazi, there were the Hohokam, who built complex irrigation systems near what is now Phoenix. And then came the Salado, "a massive cultural convergence based in east-central Arizona, where migrants collided with numerous indigienous heritages that had been in place for centuries." (Like "Anasazi," the name refers to an epoch rather than a unified tribe.) At Paquimé, a vibrant people kept birds for sport and food, built great houses and watered their fields. By the end of the 15th century, some 200 years after the disappearance of the Anasazi, all these indigenes were gone. When the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, the "probably met with only small, scattered populations, feeble resistance to thundering columns of conquistadors clad in leather and steel."I've been fascinated by this stuff at least since 2005, when I visited some Anasazi ruins in Canyon de Chelly on a trip to Arizona:

Here's another — the latest by the ecologist and poet Gary Snyder:

How many times

have I thrown you

back on the fire

And here's another:

All three of these books are about the same thing.For the past several billion years evolution on Earth has been driven by small-scale incremental forces such as sexual selection, punctuated by cosmic-scale disruptions.plate tectonics, planetary geochemistry, global climate shifts, and even extraterrestrial asteroids. Sometime in the last century that changed. Today the guiding hand of evolution is unmistakably human, with earth-shattering consequences.

The fossil record and statistical studies suggest that the average rate of extinction over the past hundred million years has hovered at several species per year. Today the extinction rate surpasses 3,000 species per year and is accelerating rapidly — it may soon reach the tens of thousands annually. In contrast, new species are evolving at a rate of less than one per year.

Over the next 100 years or so as many as half of the Earth's species, representing a quarter of the planet's genetic stock, will either completely or functionally disappear. The land and the oceans will continue to teem with life, but it will be a peculiarly homogenized assemblage of organisms naturally and unnaturally selected for their compatibility with one fundamental force: us. Nothing — not national or international laws, global bioreserves, local sustainability schemes, nor even "wildlands" fantasies — can change the current course. The path for biological evolution is now set for the next million years. And in this sense "the extinction crisis" — the race to save the composition, structure, and organization of biodiversity as it exists today — is over, and we have lost....

The space goes on.

But the wet black brush,

tip drawn to a point,

lifts away.

- Gary Snyder

© 2007 John Baez

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu