|

|

|

This week I'd like to report on some cool things people have been explaining to me. The science fiction writer Greg Egan has been helping me understand Klein's quartic curve, and the mathematician Darin Brown has been explaining the analogy between geodesics and prime numbers. The two subjects even overlap slightly!

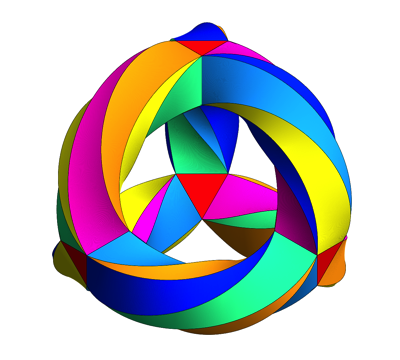

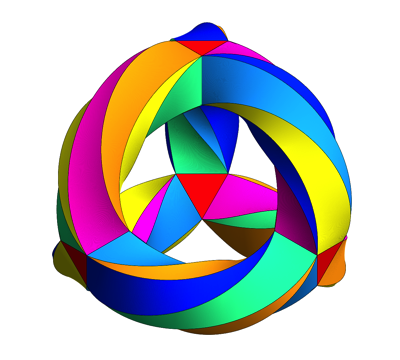

Last week I talked about Klein's quartic curve. This led Gerard Westendorp and Mike Stay to draw some pictures of it, and their ideas helped Greg Egan create this really nice picture:

1) Greg Egan, Klein's quartic curve, http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/mathematical/KleinDual.png

It looks sort of tetrahedral at first glance, but if you look carefully you'll see that topologically speaking, it's a 3-holed torus. It's tiled by triangles, with 7 meeting at each vertex. So, it's the Klein quartic curve!

Perhaps I should explain. Last week I talked about a tiling of the hyperbolic plane by regular heptagons with 3 heptagons meeting at each vertex. Dual to this is a tiling of the hyperbolic plane by equilateral triangles with 7 triangles meeting at each vertex. We can take a quotient space of this by a certain symmetry group and get a 3-holed torus tiled by 56 triangles with 7 meeting at each vertex. This is what Egan drew!

With this picture you can almost see the 168 symmetries of Klein's quartic curve.

First, you can take any vertex and twist it, causing the 7 triangles that meet at this vertex to cycle around. It's not obvious that this is a symmetry of the whole tiled surface, but it is. This gives a 7-element symmetry group.

Second, the whole thing looks like a tetrahedron, so it inherits the rotational symmetries of a tetrahedron. This gives a more obvious 12-element symmetry group.

7 × 12 = 84, so how do we get a total of 168 symmetries?

Well, there's also a 2-fold symmetry that corresponds to turning the tetrahedron inside out! And Egan made a wonderful movie of this. If a picture is worth a thousand words, this is worth about a million:

2) Greg Egan, Turning Klein's quartic curve inside out, http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/mathematical/KleinDualInsideOut.gif

So, we get a total of 7 × 24 = 168 symmetries.

Even better, if you watch carefully, you'll see that the tetrahedron in Egan's movie gets reflected as it turns inside out. More precisely, if you follow the four corners of the tetrahedron, you'll see that two come back to where they were, while the other two get switched. So, this symmetry acts as a reflection, or odd permutation, of the 4 corners. The rotations act as even permutations of the corners.

This means that the Klein quartic has 24 symmetries forming a group isomorphic to the rotation/reflection symmetry group of a tetrahedron. Algebraically speaking, this group is S4: the permutations of 4 things.

This group is also the rotational symmetry group of a cube. In fact, Egan was able to spot a hidden cube lurking in his picture! Can you?

If you look carefully, you'll see each corner of his tetrahedral gadget is made of a little triangular prism with one triangle facing out and one facing in: for example, the pink triangle staring you right in the face, or the light blue one on top. Since 4 × 2 = 8, there are 8 of these triangles. Abstractly, we can think of these as the 8 corners of a cube! They aren't really, but we can pretend. The way these 8 triangles come in pairs corresponds to how the vertices of a cube come in diagonally opposite pairs.

Using this, you can see that the group S4 acts on these 8 triangles in precisely the same way it acts via rotations on the vertices of a cube.

In fact, you can even draw a picture of a cube on the Klein quartic by drawing suitable curves that connect the centers of these 8 triangles! It's horribly distorted, but topologically correct. Part of the distortion is caused by embedding the Klein quartic in ordinary 3d Euclidean space. If we gave the Klein quartic the metric it inherits from the hyperbolic plane, the edges of the cube would be geodesics.

This remark also helps us see something else. The Klein quartic is tiled by 56 triangles. 8 of them give the cube we've just been discussing. In Egan's picture these triangles look special, since they lie at the corners of his tetrahedral gadget. But this is just an illusion caused by embedding the Klein quartic in 3d space. In reality, the Klein quartic is perfectly symmetrical: every triangle is just like every other. So in fact there are lots of these cubes, and every triangle lies in some cube.

But this is where it gets really cool. In fact, each triangle lies in just one cube. So, there's precisely one way to take the 56 triangles and divide them into 7 bunches of 8 so that each bunch forms a cube.

So: the symmetry group of the Klein quartic acts on the set of cubes, which has 7 elements.

But as I explained last week, this symmetry group also acts on the Fano plane, which has 7 points.

This suggests that cubes in the Klein quartic naturally correspond to points of the Fano plane. And Egan showed this is true!

He showed this by showing more. The Fano plane also has 7 lines. What 7 things in the Klein quartic do these lines correspond to?

Anticubes!

You see, the cubes in the Klein quartic have an inherent handedness to them. You can go between the 8 triangles of a given cube by following certain driving directions, but these driving directions involve some left and right turns. If you follow the mirror-image driving directions with "left" and "right" switched, you'll get an anticube.

Apart from having the opposite handedness, anticubes are just like cubes. In particular, there's precisely one way to take the 56 triangles and divide them into 7 bunches of 8 so that each bunch forms an anticube.

Here's a picture:

3) Greg Egan, Cubes and anticubes in the Klein quartic curve, http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/KleinFigures.gif

Each triangle has a colored circle and a colored square on it. There are 7 colors. The colored circle says which of the 7 cubes the triangle belongs to. The colored square says which of the 7 anticubes it belongs to.

If you stare at this picture for a few hours, you'll see that each cube is completely disjoint from precisely 3 anticubes. Similarly, each anticube is completely disjoint from precisely 3 cubes.

This is just like the Fano plane, where each point lies on 3 lines, and each line contains 3 points!

So, we get a vivid way of seeing how every figure in the Fano plane corresponds to some figure in the Klein quartic curve. This is why they have the same symmetry group.

This is an excellent example of Klein's Erlangen program for reducing geometry to group theory, which I discussed in "week213". Here we are beginning to see how two superficially different geometries are secretly the same:

FANO PLANE KLEIN'S QUARTIC CURVE

7 points 7 cubes

7 lines 7 anticubes

incidence of points and lines disjointness of cubes and anticubes

However, we're only half done! We've seen how to translate simple

figures and indicence relations in the Fano plane to complicated ones

in Klein's quartic curve. But, we haven't figured out translate back!

KLEIN'S QUARTIC CURVE FANO PLANE

24 vertices ???

84 edges ???

56 triangular faces ???

incidence of vertices and edges ???

incidence of edges and faces ???

Here I'm talking about the tiling of Klein's quartic curve by 56

equilateral triangles. We could equally well talk about its tiling

by 24 regular heptagons, which is the Poincare dual. Either way, the

puzzle is to fill in the question marks. I don't know the answer!

To conclude - at least for now - I want to give the driving directions that define a "cube" or an "anticube" in Klein's quartic curve. Say you're on some triangle and you want to get to a nearby triangle that belongs to the same cube. Here's what you do:

hop across any edge,Or, suppose you're on some triangle and you want to get to another that's in the same anticube. Here's what you do:

turn right,

hop across the edge in front of you,

turn left,

then hop across the edge in front of you.

hop across any edge,(If you don't understand this stuff, look at the picture above and see how to get from any circle or square to any other circle or square of the same color.)

turn left,

hop across the edge in front of you,

turn right,

then hop across the edge in front of you.

You'll notice that these instructions are mirror-image versions of each other. They're also both 1/4 of the "driving directions from hell" that I described last time. In other words, if you go LRLRLRLR or RLRLRLRL, you wind up at the same triangle you started from. You'll have circled around one face of a cube or anticube!

In fact, your path will be a closed geodesic on the Klein quartic curve... like the long dashed line in Klein and Fricke's original picture:

4) Klein and Fricke, Klein's quartic curve with geodesic, http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/Klein168.gif

Next, a little about geodesics and prime numbers. I've just been talking a little about geodesics in the Klein quartic, which is the quotient

H/G

of the hyperbolic plane H by a certain group G which I explained last week. This group, usually called Γ(7), is a nice example of a "Fuchsian group" - that is, a discrete subgroup of the isometries of the hyperbolic plane.

Darin Brown and his thesis advisor Jeff Stopple at U. C. Santa Barbara have been thinking about geodesics in H/G for other Fuchsian groups G, and their relation to number theory:

5) Jeff Stopple, A reciprocity law for prime geodesics, J. Number Theory 29 (1988), 224-230.

6) Darin Brown, Lifting properties of prime geodesics on hyperbolic surfaces, Ph.D. thesis, U. C. Santa Barbara, 2004.

I'd really like to learn about this, because it connects all sorts of stuff I dream of understanding someday, especially quantum chaos ("week190"), zeta functions in physics and number theory ("week199"), and Galois theory as a theory of covering spaces ("week205"). Also, it involves a big mysterious analogy, and I always like those!

I don't understand this stuff well enough to try a full-fledged explanation yet, so I'll just give a vague sketch. A "prime geodesic" in a Riemannian manifold X is a closed geodesic

f: S1 → X

that cycles around just once. In other words, f should be one-to-one.

We say a closed geodesic is the "nth power" of a prime one if it's just like the prime one but it cycles around n times. Every closed geodesic is the nth power of a prime one in a unique way.

If we have a Fuchsian group G, H/G is a surface with a Riemannian metric. It looks locally like the hyperbolic plane, so it's called a "hyperbolic surface". And, we can look at prime geodesics in it.

If G' is a subgroup of G, we get a covering map

H/G' → H/G

so we can ask about lifting prime geodesics in H/G to closed geodesics in H/G'. There can be a bunch of ways to do this, so we say a prime geodesic in H/G "splits" into powers of prime geodesics up in H/G'.

If you know any number theory - reading "week205" should be enough - this should remind you of how a prime ideal in some algebraic number field can "split" into prime ideals in an extension of this field, and/or "ramify" into powers of prime ideals.

And indeed, Darin Brown has found a big mysterious analogy that goes like this:

(Here by "prime ideal of K" we mean a prime ideal in the ring of algebraic integers of K.)Number field K Hyperbolic surface H/G Field extension K' of K Covering p: H/G' → H/G Galois group Gal(K'/K) Deck transformation group Aut(p) Prime ideal Q of K Prime geodesic f in H/G Prime ideal Q' lying over Q Prime geodesic f' lying over f Splitting of prime ideal Q of K' Lifting of prime geodesic f to H/G' Norm N(Q) of ideal Q Norm N(f) of closed geodesic f Frobenius conjugacy class of Q Frobenius conjugacy class of f Artin L-function Selberg zeta function

But this is more than an analogy: there's even a way to associate number fields to certain hyperbolic surfaces! The reason is that often Fuchsian groups will consist of matrices whose entries lie in some number field.

I would like to understand the Selberg zeta function and its relation to quantum mechanics. The Selberg zeta function is related to closed geodesics, which are periodic classical trajectories, while the zeta function of a Laplacian is related to periodic quantum trajectories (namely eigenfunctions of the Laplacian). So, the two are related. I know there's a lot of cool stuff going on here - especially since the motion of a particle on a hyperbolic surface tends to be chaotic, so "quantum chaos" rears its ugly head. But, I don't understand any of the details.

In some notes on quantum chaos, Gutzwiller wrote:

The classical periodic orbits are a crucial stepping stone in the understanding of quantum mechanics, in particular when then classical system is chaotic. This situation is very satisfying when one thinks of Poincaré who emphasized the importance of periodic orbits in classical mechanics, but could not have had any idea of what they could mean for quantum mechanics. The set of energy levels and the set of periodic orbits are complementary to each other since they are essentially related through a Fourier transform. Such a relation had been found earlier by the mathematicians in the study of the Laplacian operator on Riemannian surfaces with constant negative curvature. This led to Selberg's trace formula in 1956 which has exactly the same form, but happens to be exact. The mathematical proof, however, is based on the high degree of symmetry of these surfaces which can be compared to the sphere, although the negative curvature allows for many more different shapes.When I get serious, I'll read these:

7) M. C. Gutzwiller, Chaos in Classical and Quantum Mechanics, Springer, Berlin, 1990.

8) Predrag Cvitanovic, Roberto Artuso, Per Dahlqvist, Ronnie Mainieri, Gregor Tanner, Gabor Vattay, Niall Whelan and Andreas Wirzba, Chaos: Classical and Quantum, available at http://www.nbi.dk/ChaosBook/

9) Svetlana Katok, Fuchsian Groups, U. Chicago Press, Chicago, 1992.

10) J. Elstrodt, F. Grunewald, and J. Mennicke, Groups Acting on Hyperbolic Space, Springer, Berlin, 1998.

11) Peter Sarnak, Quantum chaos, symmetry and zeta functions, in Current Developments in Mathematics, 1997, eds R. Bott et al., International Press, Boston, 1999, pp. 127-159.

12) C. Schmit, Quantum and classical properties of some billiards on the hyperbolic plane, in Chaos and Quantum Physics, eds. M.-J. Giannoni et al., Elsevier, New York, 1991, pp. 333-369.

For a nice pop treatment of quantum chaos and the Riemann hypothesis, try this:

13) Martin Gutzwiller, Quantum chaos, Scientific American, January 1992. Also available at http://www.maths.ex.ac.uk/~mwatkins/zeta/quantumchaos.html

Greg Egan wrote me the following after I suggested a relation between the Klein quartic curve and 3d Minkowski spacetime over the field Z/7 - a relation that he later exploited in some fascinating ways.

Hi

Thanks for all the Lorentz group stuff! This will take me a while to

digest.

In the meantime, here are some more translations between the geometries.

Every cube intersects 4 anticubes, and any pair of cubes, between them,

intersect 6 anticubes (two of the 4 for each will always be shared). So

together the pair of cubes single out one anticube: the 7th one that

neither of them intersect. This is analogous to the fact that any two

Fano points single out a Fano line.

I'll write anti({c1,c2}) for the anticube singled out by a pair of cubes,

and similarly cube({a1,a2}) for the cube singled out by a pair of

anticubes. In the scheme used in this diagram:

both functions have identical outputs for the same input colours:

anti({c1,c2}) and cube({a1,a2})

=================================

R O Y G LB P DB

----------------------------

R | - DB R DB Y Y R

O | DB - P DB P O O

Y | R P - LB P LB R

G | DB DB LB - G LB G

LB | Y P P G - Y G

P | Y O LB LB Y - O

DB | R O R G G O -

----------------------------

Now for some actual translations.

Klein's Quartic Curve Fano plane

--------------------- ----------

28 pairs of opposite 28 choices of a point

triangular faces and a non-incident line,

{p,l}.

p1

(*)

----------- l1

7 x 4 = 28

In Klein's quartic curve, we specify a pair of opposite triangular faces

by picking one of seven cubes, then one of four anticubes that intersect

it. The intersection is a pair of triangular faces which are diagonally

opposite each other both on the cube and on the anticube. The 56 order-3

elements of G preserve these pairs of triangular faces, and consist of

rotations by 1/3 and 2/3 turns for each such pair.

Triangular faces Pairings of points and

sharing an edge non-incident lines {p1,l1} and

{p2,l2} having p1 incident on l2 and

p2 incident on l1.

p1

----(*)----- l2

----(*)----- l1

p2

In Klein's quartic curve, whenever two triangular faces share an edge,

the cube each face belongs to will be disjoint from the anticube that

the other face belongs to. This can be checked by noting that the colour

of the anticube appears in the row for anti(c,.).

If you inspect a triangle and the three neighbours that share edges with

it, the neighbours will always belong to the three anticubes disjoint

from the cube the central triangle belongs to, i.e. they will have

exactly the three colours appearing in the row for anti(c,.)

84 edges 84 choices of {p1,l1} and {p2,l2}

non-incident, but {p1,l2} and {p2,l1}

incident.

p1

----(*)----- l2

----(*)----- l1

p2

or equivalently:

84 choices of 3 non-colinear points,

with one point singled out. In this

definition, the special 3rd point is

the one point shared by l1 and l2

of the previous definition.

(*) p1

\

\ l2

\

(*) p3

/

/ l1

/

(*) p2

We can count this as (7 choose 3) triples,

minus 7 triples that are colinear, times

three for three choices of distinguished

point:

((7 choose 3) - 7) x 3 = 28 x 3 = 84

In Klein's quartic curve, we specify an edge by picking a pair of cubes

{c1,c2} and then a distinguished third one, c3, so that the three aren't

all disjoint from any one anticube. This means that, between them, they

must intersect all seven anticubes. So the third cube must be one that

intersects anti({c1,c2}). There are exactly 4 of these (and c1 and c2

aren't among them, by definition). So another way of counting the total

is (7 choose 2) x 4 = 21 x 4 = 84 choices.

To identify the particular edge, suppose we've chosen {{c1,c2},c3} as our

cubes. Then {c1, anti({c2,c3})} is a cube and an anticube that

intersects it, which specifies a pair of diagonally opposite triangular

faces, and the same is true of {c2, anti({c1,c3})}. There is a unique

edge where two of these triangles meet.

For example, if we pick {{red, orange}, yellow} then we have {red,

anti-purple} and {orange, anti-red}. Both cube/anticube choices specify

two triangles each, but there is only one edge that belongs to both a

{red, anti-purple} and an {orange, anti-red} triangle.

To reverse the process, if we look at the cube/anticube markings on the

triangles either side of some edge, and they are {c1,a1} and {c2,a2},

then we can describe this edge by {{c1,c2},cube({a1,a2})}.

Triangular faces Pairings of points and non-incident

each sharing an lines {p1,l1} and {p2,l2} having

edge with a common either p1 incident on l2 or p2

neighbour, but not incident on l1, but not both.

each other. (This

is sufficient, but p1 [or p2]

not necessary, for -----(*)-------- l2 [or l1]

them to share a

vertex.) ---------------- l1 [or l2]

(*)

p2 [or p1]

In Klein's quartic curve, as you go around a triangle anticlockwise and

look at its three (edge-sharing) neighbours, the cube a triangle belongs

to will be disjoint from the anticube of the triangle that follows, but

the anticube it belongs to will intersect the cube of the triangle that

follows. (But what the sense of the rotation means in the Fano plane

depends on whether we map cubes to points and anticubes to lines or vice

versa!)

24 vertices 168 pairings of points and non-incident

lines {p1,l1} and {p2,l2} having

either p1 incident on l2 or p2

incident on l1, but not both.

p1 [or p2]

-----(*)-------- l2 [or l1]

---------------- l1 [or l2]

(*)

p2 [or p1]

There are:

28 choices for {p1, l1}

x 3 choices for l2 passing through p1

x (7-5)=2 choices for p2 not in l1 or l2

This count identifies each vertex

as shared by common neighbours of

a particular triangle, so we expect

to count each vertex 7 times for the

seven triangles.

We could double this to count for

swapping the role of p1 and p2, and then

we'd be counting each vertex twice

as often: once going anticlockwise

between each pair of neighbours, and

once going clockwise.

This is all a bit strange and inconvenient! I can pin down an edge, but

I haven't really pinned down a single face, or a way to count a vertex

just once. I guess the answer for a vertex is to talk about an

equivalence class of the structures:

p1 [or p2]

-----(*)-------- l2 [or l1]

---------------- l1 [or l2]

(*)

p2 [or p1]

where we mod out by Z/7 and "gauge fix" l1. Every vertex is surrounded

by 7 triangular faces encompassing all seven cubes and all seven

anticubes, so these equivalence classes do fix a single vertex.

Best wishes

Greg

both functions have identical outputs for the same input colours:

anti({c1,c2}) and cube({a1,a2})

=================================

R O Y G LB P DB

----------------------------

R | - DB R DB Y Y R

O | DB - P DB P O O

Y | R P - LB P LB R

G | DB DB LB - G LB G

LB | Y P P G - Y G

P | Y O LB LB Y - O

DB | R O R G G O -

----------------------------

Now for some actual translations.

Klein's Quartic Curve Fano plane

--------------------- ----------

28 pairs of opposite 28 choices of a point

triangular faces and a non-incident line,

{p,l}.

p1

(*)

----------- l1

7 x 4 = 28

In Klein's quartic curve, we specify a pair of opposite triangular faces

by picking one of seven cubes, then one of four anticubes that intersect

it. The intersection is a pair of triangular faces which are diagonally

opposite each other both on the cube and on the anticube. The 56 order-3

elements of G preserve these pairs of triangular faces, and consist of

rotations by 1/3 and 2/3 turns for each such pair.

Triangular faces Pairings of points and

sharing an edge non-incident lines {p1,l1} and

{p2,l2} having p1 incident on l2 and

p2 incident on l1.

p1

----(*)----- l2

----(*)----- l1

p2

In Klein's quartic curve, whenever two triangular faces share an edge,

the cube each face belongs to will be disjoint from the anticube that

the other face belongs to. This can be checked by noting that the colour

of the anticube appears in the row for anti(c,.).

If you inspect a triangle and the three neighbours that share edges with

it, the neighbours will always belong to the three anticubes disjoint

from the cube the central triangle belongs to, i.e. they will have

exactly the three colours appearing in the row for anti(c,.)

84 edges 84 choices of {p1,l1} and {p2,l2}

non-incident, but {p1,l2} and {p2,l1}

incident.

p1

----(*)----- l2

----(*)----- l1

p2

or equivalently:

84 choices of 3 non-colinear points,

with one point singled out. In this

definition, the special 3rd point is

the one point shared by l1 and l2

of the previous definition.

(*) p1

\

\ l2

\

(*) p3

/

/ l1

/

(*) p2

We can count this as (7 choose 3) triples,

minus 7 triples that are colinear, times

three for three choices of distinguished

point:

((7 choose 3) - 7) x 3 = 28 x 3 = 84

In Klein's quartic curve, we specify an edge by picking a pair of cubes

{c1,c2} and then a distinguished third one, c3, so that the three aren't

all disjoint from any one anticube. This means that, between them, they

must intersect all seven anticubes. So the third cube must be one that

intersects anti({c1,c2}). There are exactly 4 of these (and c1 and c2

aren't among them, by definition). So another way of counting the total

is (7 choose 2) x 4 = 21 x 4 = 84 choices.

To identify the particular edge, suppose we've chosen {{c1,c2},c3} as our

cubes. Then {c1, anti({c2,c3})} is a cube and an anticube that

intersects it, which specifies a pair of diagonally opposite triangular

faces, and the same is true of {c2, anti({c1,c3})}. There is a unique

edge where two of these triangles meet.

For example, if we pick {{red, orange}, yellow} then we have {red,

anti-purple} and {orange, anti-red}. Both cube/anticube choices specify

two triangles each, but there is only one edge that belongs to both a

{red, anti-purple} and an {orange, anti-red} triangle.

To reverse the process, if we look at the cube/anticube markings on the

triangles either side of some edge, and they are {c1,a1} and {c2,a2},

then we can describe this edge by {{c1,c2},cube({a1,a2})}.

Triangular faces Pairings of points and non-incident

each sharing an lines {p1,l1} and {p2,l2} having

edge with a common either p1 incident on l2 or p2

neighbour, but not incident on l1, but not both.

each other. (This

is sufficient, but p1 [or p2]

not necessary, for -----(*)-------- l2 [or l1]

them to share a

vertex.) ---------------- l1 [or l2]

(*)

p2 [or p1]

In Klein's quartic curve, as you go around a triangle anticlockwise and

look at its three (edge-sharing) neighbours, the cube a triangle belongs

to will be disjoint from the anticube of the triangle that follows, but

the anticube it belongs to will intersect the cube of the triangle that

follows. (But what the sense of the rotation means in the Fano plane

depends on whether we map cubes to points and anticubes to lines or vice

versa!)

24 vertices 168 pairings of points and non-incident

lines {p1,l1} and {p2,l2} having

either p1 incident on l2 or p2

incident on l1, but not both.

p1 [or p2]

-----(*)-------- l2 [or l1]

---------------- l1 [or l2]

(*)

p2 [or p1]

There are:

28 choices for {p1, l1}

x 3 choices for l2 passing through p1

x (7-5)=2 choices for p2 not in l1 or l2

This count identifies each vertex

as shared by common neighbours of

a particular triangle, so we expect

to count each vertex 7 times for the

seven triangles.

We could double this to count for

swapping the role of p1 and p2, and then

we'd be counting each vertex twice

as often: once going anticlockwise

between each pair of neighbours, and

once going clockwise.

This is all a bit strange and inconvenient! I can pin down an edge, but

I haven't really pinned down a single face, or a way to count a vertex

just once. I guess the answer for a vertex is to talk about an

equivalence class of the structures:

p1 [or p2]

-----(*)-------- l2 [or l1]

---------------- l1 [or l2]

(*)

p2 [or p1]

where we mod out by Z/7 and "gauge fix" l1. Every vertex is surrounded

by 7 triangular faces encompassing all seven cubes and all seven

anticubes, so these equivalence classes do fix a single vertex.

Best wishes

Greg

Toby Bartels wrote:

Darin Brown wrote, in response to some questions by Squark on sci.physics.research:In Week 215, you wrote: >We say a closed geodesic is the "nth power" of a prime one >if it's just like the prime one but it cycles around n times. >Every closed geodesic is the nth power of a prime one in a unique way. The latter sentence is not quite true; you've forgotten n = 0 again! Some manifolds, like the real line, have no prime geodesics, but every (pointed) manifold has a unique unit closed geodesic, which is the geodesic that just sits at the basepoint the whole time. Given any prime geodesic f, this unit geodesic is f0. Thinking about this, I noticed that multiplication of closed geodesics, which involves (the often technically tricky) concatenation of paths, has a unique definition that's associative on the nose. (Parametrise by arclength, concatenate, then parametrise to unit length; since the paths are geodesics, the last step is also unique.) Unfortunately, this gives no way to define multiplication of closed geodesics that are (positive) powers of different primes. We could generalise to piecewise geodesics that may turn corners at the basepoint, but this seems somewhat artificial, and it doesn't have very nice properties. -- Toby

Squark wrote:

John Baez wrote:

> If G' is a subgroup of G, we get a covering map

>

> H/G' → H/G

>

> so we can ask about lifting prime geodesics in H/G to closed

> geodesics in H/G'. There can be a bunch of ways to do this, so we

> say a prime geodesic in H/G "splits" into powers of prime geodesics

> up in H/G'.

I don't quite understand how can the lift be a power, rather than just

a prime.

===

Quite true. When you lift a geodesic, once you get back to the starting

basepoint, you've gone around once up above, corr. to a prime above, so

it doesn't make sense to go around more than once! (I think this is what

the author of this comment meant.) In fact, I think it's true (I can ask

Jeff) that in a sense, there are no "ramified primes" in the geodesic

context. (There are only finitely many in the number theory context.

Actually, ramified primes are bad behaviour in a sense.) It is true,

when you lift a prime, the geodesic above has length a multiple of the

prime below, this is the analogue of the _inertial degree_, not the

ramification degree. It seems all the ramification degrees are 1, and

the magic equation reduces to degree of extension = sum(inertia

degrees).

===

> Norm N(Q) of ideal Q Norm N(f) of closed geodesic f

What is a norm of a geodesic? The length or the energy or... ?

===

Explicitly, the length of a geodesic is the (natural) log of the norm,

or equivalently, the norm is exp(length). For closed geodesics on

Γ\H, you find the norm explicitly as follows: consider the

associated hyp. conj. class {γ}, take an eigenvalue ε of an

element of this conj. class, then the norm is ε^2. The length of

the geodesic is then 2log(ε). This is independent of the choice of

γ in the conj. class.

This is why I now like to think of the norm of an ideal as a kind of

"length function on ideals".

===

> Frobenius conjugacy class of Q Frobenius conjugacy class of f

Again, what is the Frobenius on the right side here?

===

I can give 2 answers. The first answer is a cop-out, because it would

just give the concrete definition given in Jeff's paper or my thesis,

e.g. Namely, you take the associated matrix γ, and reduce entries

mod the prime Q, where Q determines the covering surface Γ(Q)\H.

This is a very concrete definition that doesn't hint at the connection

to number theory. Remember, secretly, PSL(2,q), q = norm(Q) is really

(isomorphic to) the deck transformation group of Γ(Q)\H over

Γ(H), and the Frob conj. class of a geodesic f should be a conj.

class in this deck transformation group. Conceptually, it should be an

element of the decomposition group, those deck transformations that fix

the prime geodesic above. Choosing different primes above the prime

below should give elements of the deck transformation group which are

conjugate to each other. At least, that should be the idea.

darin

Darin's description of the Frobenius associated to a prime

geodesic in H/G is a bit technical. Here's my guess as to a simpler

description:

We have a covering space of a Riemannian manifold. A geodesic down below gives an element of the fundamental group of the base. This acts as deck transformations of the cover. So, it acts on the set of prime geodesics in the cover! Indeed, it acts on the set of prime geodesics which are lifts of the geodesic down below. This is the "Frobenius automorphism" associated to the geodesic.

It's just a guess, but I feel sure it's right, or at least close. It's just like the Frobenius automorphisms in number theory - at least if we realize that a Galois group is secretly a fundamental group, as explained in "week213".

© 2005 John Baez

baez@math.removethis.ucr.andthis.edu

|

|

|