Lisa and I are in Edinburgh until January 9th of next year, for the

second half of my Leverhulme Fellowship. This time we're staying in

Mike Fourman's house on St. Leonard's Bank, a small quiet street at

the very edge of town. Across the street the land slopes suddenly

down into a park, and back up to the formation called Arthur's Seat: an

extinct volcano from the Carboniferous Period, which was carved into

its present shape by more recent glaciers. We have a great view of

Arthur's Seat from our bedroom window, as shown here. If you look

carefully you can see someone standing on it.

July 11, 2023

In my June 18th diary entry, we

figured out all the scales where we choose 7 notes from the 12 notes

in the usual chromatic scale, with the property that the biggest

step between notes is a whole tone.

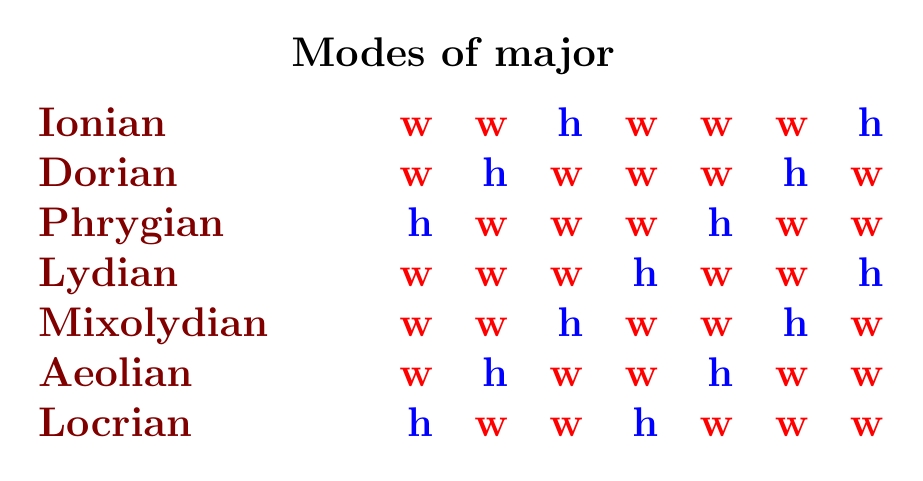

We saw these scales come in three sets of 7:

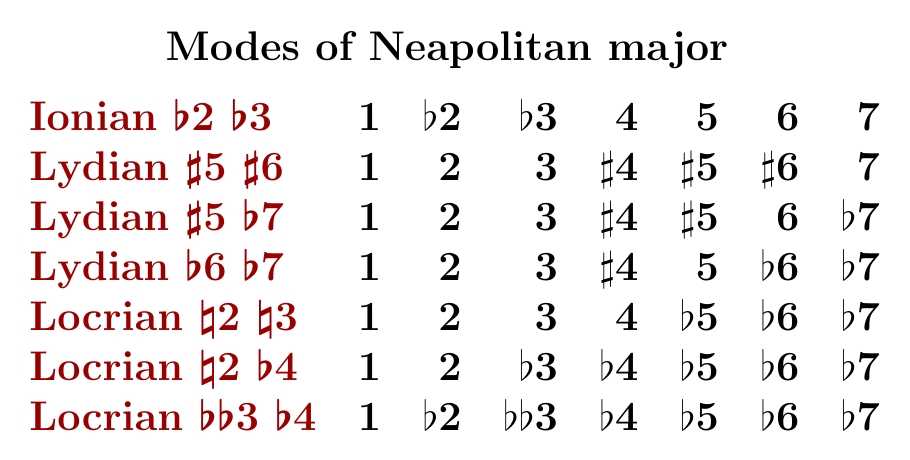

I discussed all but the last seven in Part 4. So let's look at these now!

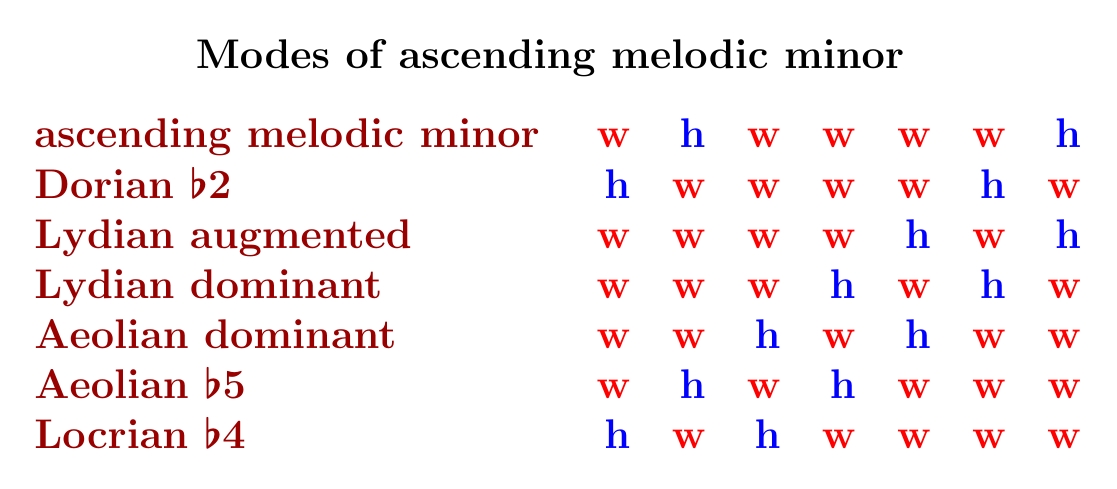

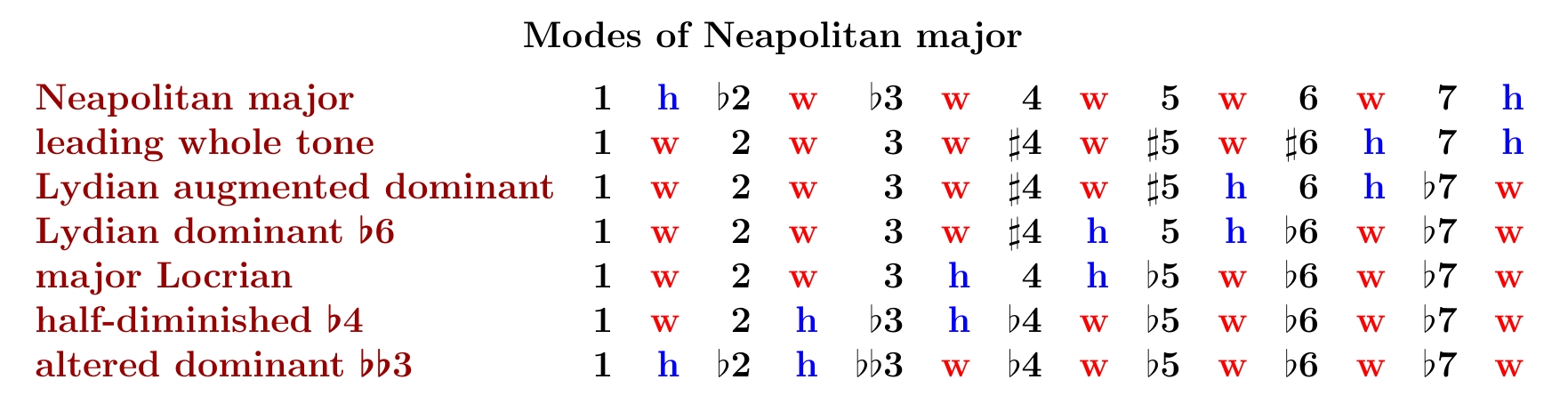

We can use the above chart to work out which scale degrees appear in these scales:

Because three consecutive notes differ by half-tones, these scales can have a lot of sharps or flats! This makes these scales more gnarly — and much more rarely used! — than those we've studied before. If the three consecutive notes come near the end we get a lot of sharps: the extreme case is the leading whole tone scale, with 3 sharps. If the three consecutive notes come near the beginning we get a lot of flats: the extreme case is the altered dominant ♭♭3 scale, which has 5 flats and one double flat!

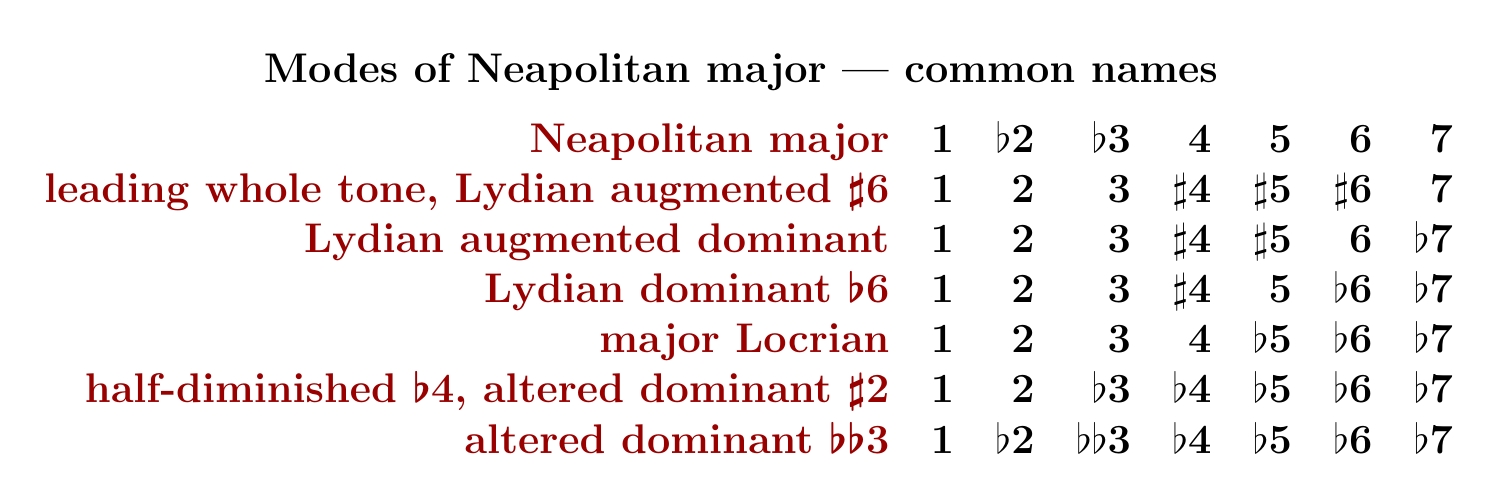

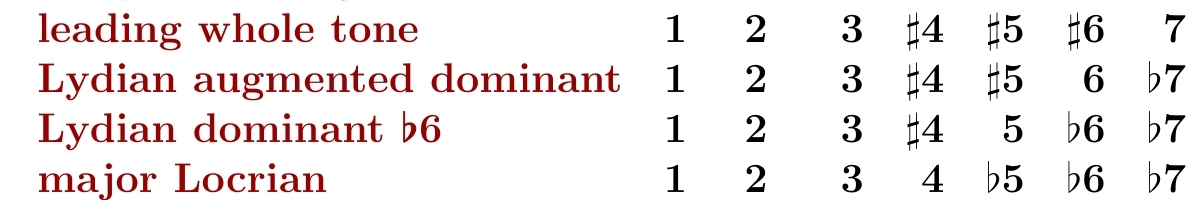

If the above chart is too busy for you, you can just look at the scale degrees:

Beware: some of the scales go by more than one name. Here are some of their more common names:

I tried to more systematically describe these scales as variants of modes of the major scale. However, to describe these scales this way, we always need to raise or lower at least two notes, so we get fairly complicated names:

Worse, the scales we're trying to describe can be obtained by modifying two notes of several different modes of the major scale. For example, besides calling Neapolitan major "Ionian ♭2 ♭3", we could also call it "Dorian ♭2 ♮6". So, I decided that this naming system was not especially useful. So, let's listen to these 7 scales!

Since scales with a flatted 3rd are usually considered minor, this makes the name 'Neapolitan major' very peculiar! There is also 'Neapolitan minor' scale, which is just the same except it also has the 6th flatted. But that's not really a great explanation of why Neapolitan major is called 'major'.

One peculiarity of Neapolitan major is that the tonic, that is the first scale degree, the most important note in the scale, is separated by a half-step from both its neighbors. Also, this is the only mode we'll talk about today that is the same when inverted.

Yet another cool feature is that you can play 6 augmented triads in this scale, which lets you play some really haunting melodies! But I'm not trying to get into triads here, so I should let Tomasso Zillio play these for you:

We are getting into weird enough scales that I'll also need to refer to some of the computer-generated videos by Ian Ring, who is a serious expert on scales. If you think I'm nerding out, watch his video on Neapolitan major:

It's called the 'leading whole tone scale' because it's the whole tone scale with one extra note added, the leading tone. Huh? Well, the whole tone scale is the 6-note scale where each note is separated from the next by a whole tone:

It was made famous by Debussy and lots of corny movie sound-tracks where someone 'goes into a dream'. One reason for its eerie sound is that it's so symmetrical that the tonic doesn't stand out at all: any note could equally well be the tonic. But we can break the symmetry by adding the 7th scale degree:

The 7th is also called the leading-tone because it yearns to move up a half step to the 8. So, the resulting scale is called the 'leading whole tone scale', and it's not so free-floating as the whole-tone scale.

The leading whole tone scale is also called 'Lydian augmented ♯6'. Remember, Lydian is the brightest mode of the major scale:

When we also sharp the 5 the scale becomes even brighter — and it contains the augmented triad 1 3 ♯5, so we call it Lydian augmented:

Lydian augmented is the brightest mode of the ascending melodic minor scale! I talked about both Lydian and Lydian augmented last time. But when we take Lydian augmented and sharp the 6 we get an even brighter scale, Lydian augmented ♯6:

In fact, this is the brightest of all the 21 scales I've been talking about! But remember, bright does not mean 'happy': it means that the notes are pushed up higher. Lydian augmented ♯6 is what I'd call uncomfortably bright.

It's called 'dominant' because it contains the notes 1 3 ♭7, which are the most important notes in a dominant 7th chord based on the 1. Of course you can also can also think of this scale as the Lydian dominant scale with a sharp 5.

Ian Ring calls this scale Aeroptian:

Ian Ring says this scale is called Lydian minor, but he admits this is a bad name since the 3 is not flat:

Recall that Locrian is the darkest mode of the major scale:

It's classified as a minor scale since the 3 is flat. So if we make the 3 natural, we get 'major Locrian'!

By the way, there's a beautiful pattern in the sharps and flats of the second through fifth modes of Neapolitan major:

The flats keep invading from above while the sharps keep retreating! So these scales keep getting darker. But even darker scales are to come... darker than any we've seen so far!

Locrian is the darkest mode of the major scale — and also the least loved, because two of the pillars of western harmony, the 5 and the 7, have both sunk into the mire of flatness. The third pillar is the 4, and in the half-diminished ♭6 scale this too has been flatted! So, don't expect to see many tunes written in this scale.

But why is this scale called ''half-diminished ♭4'? A major 7th chord starting at the 1 contains the notes

There are several important variants of this hugely important chord. In a dominant 7th chord the 7 is flatted:

In a minor 7th chord the 3 is also flatted:

In a half-diminished 7th chord we go ahead and flat the 5 too:

And in a diminished 7th chord we go still further, but let's not go there now. The half-diminished scale is a scale which fleshes out the half-diminished 7th chord with other notes from the natural minor scale:

It's the 6th mode of ascending melodic minor, so I discussed it last time. I called it Aeolian ♭5 since the natural minor scale is also called the Aeolian mode, and here we have taken that and flatted the 5. Anyway, if we take the half-diminished scale and now flat the 4, we get the half-diminished ♭4 scale:

Ian Ring calls it 'Storian' for some reason:

Here the first, second and third notes are each a half-step apart, so the second is ♭2 and the third is ♭♭3, and all the higher notes are flatted as well!

Why is this scale called 'altered dominant ♭♭3'? It's a variant of the altered dominant scale, which is the 7th and darkest mode of the ascending melodic minor scale:

We discussed the altered dominant scale last time under the name 'Locrian ♭4'. Every note except the 1 is flatted! When we flat the 3 a second time, we get the altered dominant ♭♭3 scale:

This is the darkest of all the 21 scales I've been discussing! It's the inverted version of the leading whole tone scale, so Ian Ring calls it the 'leading whole tone inverse scale':

I don't like how he writes this scale on the staff, because he calls the ♭2 a ♯1, etc. These notes are enharmonically equivalent — they sound the same on the piano — but the second note in a 7-note scale should be notated with a 2, not a 1.

And on this grumpy pedantic note ♪ I hereby conclude my tour of

7-note scales with the biggest step being a whole tone! As you can

see, the modes of Neapolitan major are much less familiar than those

of major or ascending melodic minor. However, they do give us a great

opportunity to think about the whole network of scales and how they

are related. And now I want to go off and make music with some of the

more promising ones!

July 15, 2023

Lisa and I are going to the Orkney Islands with our friends Mike Fourman and Jeanne de Luart. We'll be staying in Kirkwall but plan to visit various archaeological sites — in particular the Ness of Brodgar, on the same island. This is a complex of monumental Neolithic buildings dating from around 3000 BC. There's a dig there now, but in 2024 it'll be covered over and backfilled to save it for future archaeologists. So this may be the last time to see it before our civilization crashes.

Speaking of which: due to the climate crisis I try to avoid flying

around and spewing out carbon, but I haven't managed to completely

resist traveling, so I've compromised by only making one long flight

this year, for a 6-month visit to Edinburgh. While here I will

indulge myself in some local travel. The bleak and northerly Orkney

Islands, with their many Neolithic sites, have always fascinated me.

July 16, 2023

Today it's so windy near Edinburgh that the price of power has gone negative!

Why does the price go negative? Apparently because it costs more to slow the turbines than to let them spin and generate power. And it costs more to dump the power somewhere than to have customers use it.

We get the pricing data in real time from here:

When the price went negative we helped out the electric company by turning on more lights. But I wish they could have stored the excess power.

For example, the Cruachan Power

Station is a pumped-storage hydroelectric power station in the

area of Argyll and Bute, Scotland. When there's too much power around

they pump water from a nearby loch to the upper reservoir, 400 meters

up. Later they release it when needed. It can generate 440

megawatts of power, and run for 22 hours when it's completely full.

July 17, 2023

When I go to Orkney this week, there's a lot I want to see!

The Ring of Brodgar is 100 meters in diameter, originally made of 60 stones. After Avebury and Stonehenge it's the greatest of the henges on the British isle — but of these three it's the most perfect circle. It was built sometime between 2500 and 2000 BC, making it the most recent structure in the 'Heart of Neolithic Orkney'. Four others are:

Orkney is very far north, so archaeologists used to think its

Neolithic culture came from the south. But now they think Orkney was

the starting place for much of the megalithic culture of the British

Isles. In Orkney this culture ended around 2000 BC. Nobody knows

why!

July 25, 2023

I don't like to fly around much anymore. But since I'm spending half

a year in Scotland I figured it wasn't too bad to take a ferry up to

the Orkney Islands,

at the northern end of this country, to see a bunch of Neolithic,

Bronze Age and Iron Age sites.

I spent all my time on the largest island, which curiously is called the 'Mainland' though it's far smaller than the main island of the British isles, to the south.

A fascinating thing about the Orkneys is that they hold the earliest megaliths in the British Isles, older than Stonehenge. At first people thought Neolithic culture spread northward, but it seems that it spread southward.

What first attracted people to these chilly northern islands? I don't know. The Neolithic settlers even had to bring deer to hunt!

One place I visited is Skara Brae, Europe's most complete Neolithic village. It's on the western shore of the Mainland.

It's one of the oldest Neolithic sites on the Orkneys, occupied from roughly 3180 BCE to about 2500 BCE. But it's remarkably sophisticated! It consists of ten clustered houses, made of flagstones. These houses included stone hearths, beds, cupboards — and even a sewer system, with drains in each house that carry water out to the ocean.

What led people to eventually abandon this site? I don't know that either. But apparently it became colder and windier in the Iron Age. Eventually it became buried under sand from the nearby beach — and it remained hidden until uncovered by a storm in 1850.

As I explored the site on a chill and windy day, I was occasionally blasted by sand. If tourism ends and Skara Brae is left to its own devices, the wind and sand will take it back.

Another great archaeological site I saw was the stone circle called the Ring of Brodgar. This is located nearby:

But unlike Skara Brae it's not on the west shore, on the Norwegian Sea. Instead, it's on a small isthmus between the Loch of Stenness and the Loch of Harray — a natural point for travelers to pass:

Most of the megalithic structures on the British Isles do not contain stone circles. The three most notable exceptions are Avebury, Stonehenge and the Ring of Brodgar. Of these, the Ring of Brodgar is the northernmost and also the most perfect circle.

It's proved difficult to date this monument, but it's generally thought to have been built between 2500 BC and 2000 BC. If so, it's the last of the great Neolithic monuments built in this region, the Ness of Brodgar. The homes of Skara Brae, for comparison, were built from about 3180 BC to 2500 BC.

The Ring of Brodgar is about 100 meters in diameter. The ring originally had about 60 stones, but only 27 are still standing now. These stones are surrounded by a circular ditch dug into the sandstone bedrock below.

As we approached the Ring of Brodgar it was chilly, windy, cloudy and a bit misty. Then it cleared up for a while. Then it started to rain. It was a mysterious and evocative experience, which set me to wondering about the ancient people who made this site.