3.4 The Route to Spin(10) via Pati-Salam

In the last section, we showed how the Pati-Salam model answers two questions

about the Standard Model:

Why are quarks and leptons so similar? Why are left and right so

different?

We were able to describe leptons as a fourth color of quark, `white', and

treat right-handed and left-handed particles on a more equal footing.

Neither of these ideas worked on its own, but together, they made

a full-fledged extension of the Standard Model, much like  and

and

, but based on seemingly different principles.

, but based on seemingly different principles.

Yet thinking of leptons as `white' should be strangely familiar, not

just from the Pati-Salam perspective, but

from the binary code that underlies both the  and the

and the

theories. There, leptons were indeed white: they all have

color

theories. There, leptons were indeed white: they all have

color

.

.

Alas, while  hints that leptons might be a fourth color, it does not

deliver on this. The quark colors

hints that leptons might be a fourth color, it does not

deliver on this. The quark colors

lie in a different irrep of  than does

than does

. So, leptons in the

. So, leptons in the  theory are white, but unlike

the Pati-Salam model, this theory

does not unify leptons with quarks.

theory are white, but unlike

the Pati-Salam model, this theory

does not unify leptons with quarks.

Yet  theory is not the only game in town when it comes to the binary

code. We also have

theory is not the only game in town when it comes to the binary

code. We also have

, which acts on the same vector space as

, which acts on the same vector space as

. As a representation of

. As a representation of

,

,

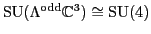

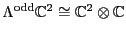

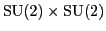

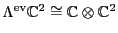

breaks up into just

two irreps: the even grades,

breaks up into just

two irreps: the even grades,

, which contain the left-handed

particles and antiparticles:

, which contain the left-handed

particles and antiparticles:

and the odd grades

, which contain the right handed particles and

antiparticles:

, which contain the right handed particles and

antiparticles:

Unlike  , the

, the

GUT really does unify

GUT really does unify

with the colors

with the colors  ,

,  and

and  , because they

both live in the irrep

, because they

both live in the irrep

.

.

In short, it seems that the

GUT, which we built as an

extension of the

GUT, which we built as an

extension of the  GUT, somehow managed to pick up

this feature of the Pati-Salam model.

How does

GUT, somehow managed to pick up

this feature of the Pati-Salam model.

How does

relate to Pati-Salam's gauge group

relate to Pati-Salam's gauge group

,

exactly? In general, we only know there is a map

,

exactly? In general, we only know there is a map

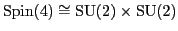

,

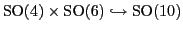

but in low dimensions, there is much more, because some groups coincide:

,

but in low dimensions, there is much more, because some groups coincide:

What really stands out is this:

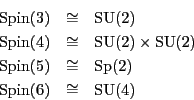

This brings out an obvious relationship between the Pati-Salam model and the

theory, because the inclusion

theory, because the inclusion

lifts to the universal covers, so we get a homomorphism

lifts to the universal covers, so we get a homomorphism

A word of caution is needed here. While  is the lift of an inclusion, it

is not an inclusion itself: it is two-to-one. This is because the universal

cover

is the lift of an inclusion, it

is not an inclusion itself: it is two-to-one. This is because the universal

cover

of

of

is a four-fold

cover, being a double cover on each factor.

is a four-fold

cover, being a double cover on each factor.

So we can try to extend the symmetries

to

to

, though this can only work if the kernel of

, though this can only work if the kernel of  acts

trivially on the Pati-Salam representation.

What is this representation like? There is an obvious

representation of

acts

trivially on the Pati-Salam representation.

What is this representation like? There is an obvious

representation of

that extends to a

that extends to a

rep.

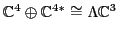

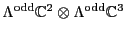

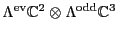

Both

rep.

Both  and

and  have Dirac spinor representations, so their

product

have Dirac spinor representations, so their

product

has a representation on

has a representation on

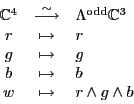

. And in fact, the obvious map

. And in fact, the obvious map

given by

is an isomorphism compatible with the actions of

on these two spaces. More concisely, this square:

on these two spaces. More concisely, this square:

commutes.

We will prove this in a moment. First though, we must check that

this representation of

is secretly

just another name for the Pati-Salam representation of

is secretly

just another name for the Pati-Salam representation of

on the space we discussed in

Section 3.3:

on the space we discussed in

Section 3.3:

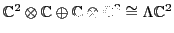

Checking this involves choosing an isomorphism between

and

and

.

Luckily, we can choose one that works:

.

Luckily, we can choose one that works:

Theorem 4

.

There exists an isomorphism of Lie groups

and a unitary operator

that make this square commute:

where the left vertical arrow is the Pati-Salam representation

and the right one is a tensor product of Dirac spinor representations.

Proof. We can prove this in pieces, by separately finding

a unitary operator

that makes this square commute:

and a unitary operator

that make this square:

commute.

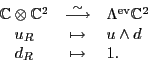

First, the  piece. It suffices to show that the Dirac spinor rep

of

piece. It suffices to show that the Dirac spinor rep

of

on

on

is isomorphic to

is isomorphic to

as a rep of

as a rep of

. We start with the action of

. We start with the action of  on

on

. This breaks up

into irreps:

. This breaks up

into irreps:

called the left-handed

and right-handed Weyl spinors, and these are dual to each

other because 6 = 2 mod 4, by a theorem that can be found

in Adams' lectures [1]. Call these representations

Since these reps are dual, it suffices just to consider one of them, say

.

.

Passing to Lie algebras, we have a homomorphism

Homomorphic images of semisimple Lie algebras are semisimple, so the image of

must lie entirely in

must lie entirely in

. In fact

. In fact

is simple, so this

nontrivial map must be an injection

is simple, so this

nontrivial map must be an injection

and because the dimension is 15 on both sides, this map is also

onto. Thus

is an isomorphism of Lie algebras, so

is an isomorphism of Lie algebras, so

is an isomorphism of the simply connected Lie

groups

is an isomorphism of the simply connected Lie

groups  and

and  :

:

Furthermore, under this isomorphism

as a representation of

.

Taking duals, we obtain an isomorphism

.

Taking duals, we obtain an isomorphism

Putting these together, we get an isomorphism

that makes this square commute:

that makes this square commute:

which completes the proof for  .

.

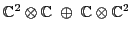

Next, the  piece. It suffices

to show that the spinor rep

piece. It suffices

to show that the spinor rep

of

of

is isomorphic to

is isomorphic to

as a rep of

as a rep of

. We start with the action of

. We start with the action of  on

on

. This

again breaks up into irreps:

. This

again breaks up into irreps:

Again we call these representations

First consider

. Passing to Lie algebras, this gives

a homomorphism

. Passing to Lie algebras, this gives

a homomorphism

Homomorphic images of semisimple Lie algebras are semisimple, so the image of

must lie entirely in

must lie entirely in

. Similarly,

. Similarly,

also takes

also takes

to

to

:

:

and we can combine these maps to get

which is just the derivative of  's representation on

's representation on

.

Since this representation is faithful, the map

.

Since this representation is faithful, the map

of Lie

algebras is injective. But the dimensions of

of Lie

algebras is injective. But the dimensions of

and

and

agree, so

agree, so

is also onto. Thus it is an isomorphism

of Lie algebras. This implies that

is also onto. Thus it is an isomorphism

of Lie algebras. This implies that

is an isomorphism of of

the simply connected Lie groups

is an isomorphism of of

the simply connected Lie groups  and

and

under which

acts on

acts on

. The

left factor of

. The

left factor of  acts irreducibly on

acts irreducibly on

, which the second

factor is trivial on. Thus

, which the second

factor is trivial on. Thus

as a rep of

as a rep of

. Similarly,

. Similarly,

as a rep of this group. Putting these together,

we get an isomorphism

as a rep of this group. Putting these together,

we get an isomorphism

that makes this square commute:

that makes this square commute:

which completes the proof for  .

.

In the proof of the preceding theorem, we merely showed that there

exists an isomorphism

making the square commute. We did not say exactly what  was.

In the proof, we built it after quietly choosing

three unitary operators, giving these isomorphisms:

was.

In the proof, we built it after quietly choosing

three unitary operators, giving these isomorphisms:

Since the remaining map

is determined by

duality, these three operators determine

is determined by

duality, these three operators determine  , and they also

determine the Lie group isomorphism

, and they also

determine the Lie group isomorphism  via the construction in our proof.

via the construction in our proof.

There is, however, a specific choice for these unitary operators that we

prefer, because this choice makes the particles in the Pati-Salam

representation

look almost exactly like

those in the

look almost exactly like

those in the  representation

representation

.

.

First, since

is spanned by

is spanned by  and

and

, the (left-handed) isospin states of the Standard Model, we really ought

to identify the left-isospin states

, the (left-handed) isospin states of the Standard Model, we really ought

to identify the left-isospin states  and

and  of the Pati-Salam model

with these. So, we should use this unitary operator:

of the Pati-Salam model

with these. So, we should use this unitary operator:

Next, we should use this unitary operator for right-isospin states:

Why? Because the right-isospin up particle is the right-handed neutrino

, which corresponds to

, which corresponds to

in the

in the  theory, but

theory, but  in the Pati-Salam model. This suggests that

in the Pati-Salam model. This suggests that  and

and  should be identified.

should be identified.

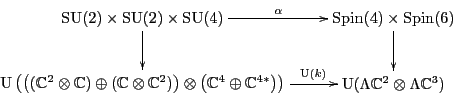

Finally, because

is spanned by the colors

is spanned by the colors  ,

,  and

and  , while

, while

is spanned by the colors

is spanned by the colors  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  , we really ought

to use this unitary operator:

, we really ought

to use this unitary operator:

Dualizing this, we get the unitary operator

These choices determine the unitary operator

With this specific choice of  , we can combine the commutative squares

built in Theorems 3 and

4:

, we can combine the commutative squares

built in Theorems 3 and

4:

to obtain the following result:

Theorem 5

.

Taking

and

and  , the

following square commutes:

where the left vertical arrow is the Standard Model representation and

the right one is a tensor product of Dirac spinor representations.

, the

following square commutes:

where the left vertical arrow is the Standard Model representation and

the right one is a tensor product of Dirac spinor representations.

The map  , which tells us how to identify

, which tells us how to identify  and

and

, is given by applying

, is given by applying  to the `Pati-Salam code' in

Table 5. This gives a binary code for the

Pati-Salam model:

to the `Pati-Salam code' in

Table 5. This gives a binary code for the

Pati-Salam model:

Table 6:

Pati-Salam binary code for first-generation fermions, where  and

and

.

.

| The Binary Code for Pati-Salam |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

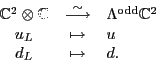

We have omitted wedge product symbols to save space. Note that if we apply the

obvious isomorphism

given by

then the above table does more than

merely resemble Table 4, which gives the

binary code for the  theory. The two tables become

identical!

theory. The two tables become

identical!

This fact is quite intriguing. We will explore its meaning

in the next section. But first, let us start by relating the

Pati-Salam model to the

theory:

theory:

Theorem 6

.

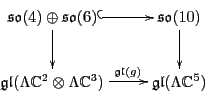

The following square commutes:

where the right vertical arrow is the Dirac spinor representation,

the left one is the tensor product of Dirac spinor representations,

and

is the homomorphism lifting the inclusion of

in

in

.

.

Proof. At the Lie algebra level, we have the inclusion

by block diagonals, which is also just the differential of the inclusion

at the Lie group level. Given how the

spinor reps are defined in terms of creation and annihilation operators, it is

easy to see that

at the Lie group level. Given how the

spinor reps are defined in terms of creation and annihilation operators, it is

easy to see that

commutes, because  is an

intertwining operator between representations

of

is an

intertwining operator between representations

of

.

That is because the

.

That is because the

part only acts on

part only acts on

, while the

, while the

part only acts on

part only acts on

.

.

But these Lie algebras act by skew-adjoint operators, so really

commutes. Since the

's and their direct sums are semisimple, so are

their images. Therefore, their images live in the semisimple part of the

unitary Lie algebras, which is just another way of saying the special unitary

Lie algebras. We get that

's and their direct sums are semisimple, so are

their images. Therefore, their images live in the semisimple part of the

unitary Lie algebras, which is just another way of saying the special unitary

Lie algebras. We get that

commutes, and this gives a commutative square in the world of

simply connected Lie groups:

This completes the proof.

This result shows us how to reach the

theory, not

through the

theory, not

through the  theory, but through the Pati-Salam model.

For physics texts that treat this issue, see for example

Zee [40] and Ross [31].

theory, but through the Pati-Salam model.

For physics texts that treat this issue, see for example

Zee [40] and Ross [31].

2010-01-11

![]() and

and

![]() , but based on seemingly different principles.

, but based on seemingly different principles.

![]() and the

and the

![]() theories. There, leptons were indeed white: they all have

color

theories. There, leptons were indeed white: they all have

color

![]() .

.

![]() hints that leptons might be a fourth color, it does not

deliver on this. The quark colors

hints that leptons might be a fourth color, it does not

deliver on this. The quark colors

![]() theory is not the only game in town when it comes to the binary

code. We also have

theory is not the only game in town when it comes to the binary

code. We also have

![]() , which acts on the same vector space as

, which acts on the same vector space as

![]() . As a representation of

. As a representation of

![]() ,

,

![]() breaks up into just

two irreps: the even grades,

breaks up into just

two irreps: the even grades,

![]() , which contain the left-handed

particles and antiparticles:

, which contain the left-handed

particles and antiparticles:

![]() GUT, which we built as an

extension of the

GUT, which we built as an

extension of the ![]() GUT, somehow managed to pick up

this feature of the Pati-Salam model.

How does

GUT, somehow managed to pick up

this feature of the Pati-Salam model.

How does

![]() relate to Pati-Salam's gauge group

relate to Pati-Salam's gauge group

![]() ,

exactly? In general, we only know there is a map

,

exactly? In general, we only know there is a map

![]() ,

but in low dimensions, there is much more, because some groups coincide:

,

but in low dimensions, there is much more, because some groups coincide:

![]() theory, because the inclusion

theory, because the inclusion

![]() lifts to the universal covers, so we get a homomorphism

lifts to the universal covers, so we get a homomorphism

![]() to

to

![]() , though this can only work if the kernel of

, though this can only work if the kernel of ![]() acts

trivially on the Pati-Salam representation.

What is this representation like? There is an obvious

representation of

acts

trivially on the Pati-Salam representation.

What is this representation like? There is an obvious

representation of

![]() that extends to a

that extends to a

![]() rep.

Both

rep.

Both ![]() and

and ![]() have Dirac spinor representations, so their

product

have Dirac spinor representations, so their

product

![]() has a representation on

has a representation on

![]() . And in fact, the obvious map

. And in fact, the obvious map

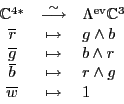

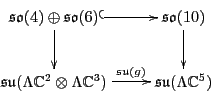

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\rm Spin}(4) \times {\rm Spin}(6) \ar[r]^-\eta \...

...3) \ar[r]^-{{\rm U}(g)} & {\rm U}(\Lambda {\mathbb C}^5) \\

}

\end{displaymath}](img661.png)

![]() is secretly

just another name for the Pati-Salam representation of

is secretly

just another name for the Pati-Salam representation of

![]() on the space we discussed in

Section 3.3:

on the space we discussed in

Section 3.3:

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\rm SU}(2) \times {\rm SU}(2) \ar[r]^-\sim \ar[d...

...thbb C}^2) \ar[r]^-\sim & {\rm U}(\Lambda {\mathbb C}^2) \\

}

\end{displaymath}](img667.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\rm SU}(4) \ar[r]^\sim \ar[d] & {\rm Spin}(6) \a...

...b C}^{4*}) \ar[r]^-\sim & {\rm U}(\Lambda {\mathbb C}^3) \\

}

\end{displaymath}](img669.png)

![]() piece. It suffices to show that the Dirac spinor rep

of

piece. It suffices to show that the Dirac spinor rep

of

![]() on

on

![]() is isomorphic to

is isomorphic to

![]() as a rep of

as a rep of

![]() . We start with the action of

. We start with the action of ![]() on

on

![]() . This breaks up

into irreps:

. This breaks up

into irreps:

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\rm Spin}(6) \ar[d] \ar[r]^\rho_{\rm{odd}}& {\rm...

...}^3) \ar[r] & {\rm U}({\mathbb C}^4 \oplus {\mathbb C}^{4*})

}

\end{displaymath}](img684.png)

![]() piece. It suffices

to show that the spinor rep

piece. It suffices

to show that the spinor rep

![]() of

of

![]() is isomorphic to

is isomorphic to

![]() as a rep of

as a rep of

![]() . We start with the action of

. We start with the action of ![]() on

on

![]() . This

again breaks up into irreps:

. This

again breaks up into irreps:

![]() . Passing to Lie algebras, this gives

a homomorphism

. Passing to Lie algebras, this gives

a homomorphism

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\rm Spin}(4) \ar[d] \ar[r]^-{\rho_{\rm{ev}}\oplu...

... \otimes {\mathbb C}\oplus {\mathbb C}\otimes {\mathbb C}^2)

}

\end{displaymath}](img704.png)

![]() look almost exactly like

those in the

look almost exactly like

those in the ![]() representation

representation

![]() .

.

![]() is spanned by

is spanned by ![]() and

and

![]() , the (left-handed) isospin states of the Standard Model, we really ought

to identify the left-isospin states

, the (left-handed) isospin states of the Standard Model, we really ought

to identify the left-isospin states ![]() and

and ![]() of the Pati-Salam model

with these. So, we should use this unitary operator:

of the Pati-Salam model

with these. So, we should use this unitary operator:

![]() is spanned by the colors

is spanned by the colors ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , while

, while

![]() is spanned by the colors

is spanned by the colors ![]() ,

, ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() , we really ought

to use this unitary operator:

, we really ought

to use this unitary operator:

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{G_{\mbox{\rm SM}}}\ar[r]^-{\beta} \ar[d]

& {\rm...

...ght) \ar[r]^-{{\rm U}(k)}

& {\rm U}(\Lambda {\mathbb C}^5)

}

\end{displaymath}](img716.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{G_{\mbox{\rm SM}}}\ar[r]^-\theta \ar[d] & {\rm...

...}(\Lambda {\mathbb C}^2 \otimes \Lambda {\mathbb C}^3) \\

}

\end{displaymath}](img719.png)

![]() , which tells us how to identify

, which tells us how to identify ![]() and

and

![]() , is given by applying

, is given by applying ![]() to the `Pati-Salam code' in

Table 5. This gives a binary code for the

Pati-Salam model:

to the `Pati-Salam code' in

Table 5. This gives a binary code for the

Pati-Salam model:

![]() theory:

theory:

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\rm Spin}(4) \times {\rm Spin}(6) \ar[r]^-\eta \...

...3) \ar[r]^-{{\rm U}(g)} & {\rm U}(\Lambda {\mathbb C}^5) \\

}

\end{displaymath}](img661.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\mathfrak{so}}(4) \oplus {\mathfrak{so}}(6) \ar@...

...thbb C}^3) \ar[r]^-{\u (g)} & \u (\Lambda {\mathbb C}^5) \\

}

\end{displaymath}](img744.png)

![\begin{displaymath}

\xymatrix{

{\rm Spin}(4) \times {\rm Spin}(6) \ar[r]^-\eta \...

...}^3) \ar[r]^-{{\rm SU}(g)} & {\rm SU}(\Lambda {\mathbb C}^5)

}

\end{displaymath}](img747.png)

![]() theory, not

through the

theory, not

through the ![]() theory, but through the Pati-Salam model.

For physics texts that treat this issue, see for example

Zee [40] and Ross [31].

theory, but through the Pati-Salam model.

For physics texts that treat this issue, see for example

Zee [40] and Ross [31].