Today is the day of Our Lady of the Holy Death, or Nuestra Señora de la Santa Muerte. She's a folk saint in Mexico, called Santa Muerte for short.

Despite condemnation by the Catholic Church, the cult of Santa Muerte is one of the fastest-growing religious movements in the world, with over 10 million followers — mainly in Mexico, Guatemala and US.

These days I tend to think we're all inherently irrational, and people working too hard to fight that — like some in the 'rationalist movement' — go even more crazy. So maybe a cult of Santa Muerte is appropriate for humanity.

There's a lot about Santa Muerte here:

Our Lady of Holy Death is a personification of death. Unlike other saints who originated in Mexican folk religion, Santa Muerte is not, herself, seen as a dead human being. She is associated with healing, protection, financial wellbeing, and assurance of a path to the afterlife.And a bit about the sociology:Although there are other death saints in Latin America, such as San La Muerte, Santa Muerte is the only female saint of death in either of the Americas. Though early figures of the saint were male, iconographically, Santa Muerte is a skeleton dressed in female clothes or a shroud, and carrying both a scythe and a globe. Santa Muerte is marked out as female not by her figure but by her attire and hair. The latter was introduced by a believer named Enriqueta Romero.

The two most common objects that Santa Muerte holds in her hands are a globe and a scythe. The scythe can symbolize the cutting of negative energies or influences. As a harvesting tool, a scythe may also symbolize hope and prosperity. Her scythe reflects her origins as the Grim Reaper ("la Parca" of medieval Spain), and can represent the moment of death, when it is said to cut a silver thread. The scythe has a long handle, indicating that it can reach anywhere. The globe represents Death's vast power and dominion over the earth, and may be seen as a kind of a tomb to which we all return.

Other objects associated with Santa Muerte include scales, an hourglass, an owl, and an oil lamp. The scales allude to equity, justice, and impartiality, as well as divine will. An hourglass indicates the time of life on earth and also the belief that death is not the end, as the hourglass can be inverted to start over. The hourglass denotes Santa Muerte's relationship with time as well as with the worlds above and below. It also symbolizes patience. An owl symbolizes her ability to navigate the darkness and her wisdom. The owl is also said to act as a messenger. A lamp symbolizes intelligence and spirit, to light the way through the darkness of ignorance and doubt. Some followers of Santa Muerte believe that she is jealous and that her image should not be placed next to those of other saints or deities, or there will be consequences

The cult of Santa Muerte is present throughout the strata of Mexican society, although the majority of devotees are from the urban working class. Most are young people, aged in their teens, twenties, or thirties, and are also mostly female. A large following developed among Mexicans who are disillusioned with the dominant, institutional Catholic Church and, in particular, with the inability of established Catholic saints to deliver them from poverty.The phenomenon is based among people with scarce resources, excluded from the formal market economy, as well as the judicial and educational systems, primarily in the inner cities and the very rural areas. Devotion to Santa Muerte is what anthropologists call a "cult of crisis". Devotion to the image peaks during economic and social hardships, which tend to affect the working classes more. Santa Muerte tends to attract those in extremely difficult or hopeless situations but also appeals to smaller sectors of middle class professionals and even the affluent. Some of her most devoted followers are those who commit petty economic crimes, often committed out of desperation, such as prostitutes, and petty thieves.

The worship of Santa Muerte also attracts those who are not inclined to seek the traditional Catholic Church for spiritual solace, as it is part of the "legitimate" sector of society. Many followers of Santa Muerte live on the margins of the law or outside it entirely. Many street vendors, taxi drivers, vendors of counterfeit merchandise, street people, prostitutes, pickpockets, petty drug traffickers and gang members who follow the cult are not practicing Catholics or Protestants, but neither are they atheists.

I'm falling in love with random permutations.

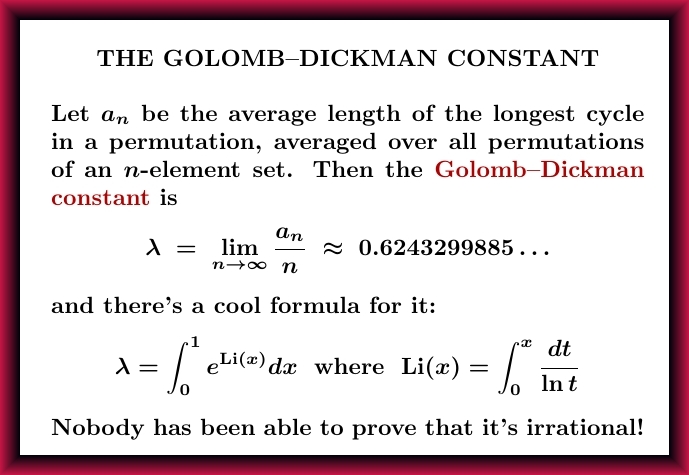

The average length of the longest cycle in a random permutation of a huge \(n\)-element set is asymptotic to \(\lambda n\) where \(\lambda\) is the Golomb–Dickman constant.

The Golomb–Dickman constant also shows up in number theory... in a very similar way! If you randomly choose a huge \(n\)-digit integer, the average number of digits of its largest prime factor is asymptotically equal to \(\lambda n\).

So, there's a connection between prime factorizations and random permutations! You can read more about this in Sections 3.10-3.12 here:

Here's another appearance of this constant. Say you randomly choose a function from a huge \(n\)-element set to itself. Then the average length of its longest periodic orbit is asymptotic to $$ \lambda \; \sqrt{\frac{\pi n}{2}} $$